Preventive Care in Nursing and Midwifery Journal

Volume 15, Issue 1 (1-2025)

Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J 2025, 15(1): 46-55 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.SSU.REC.1402.024

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Abbaaszadeh Mehrabad E, Javadi M, Heydari S, Nasiriani K. Basic life support training: Demonstration versus structured demonstration in red crescent volunteers. Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J 2025; 15 (1) :46-55

URL: http://nmcjournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-963-en.html

URL: http://nmcjournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-963-en.html

Research Center for Nursing and Midwifery Care, Comprehensive Research Institute for Maternal and Child Health, Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran , javadinurse@gmail.com

Full-Text [PDF 753 kb]

(316 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (758 Views)

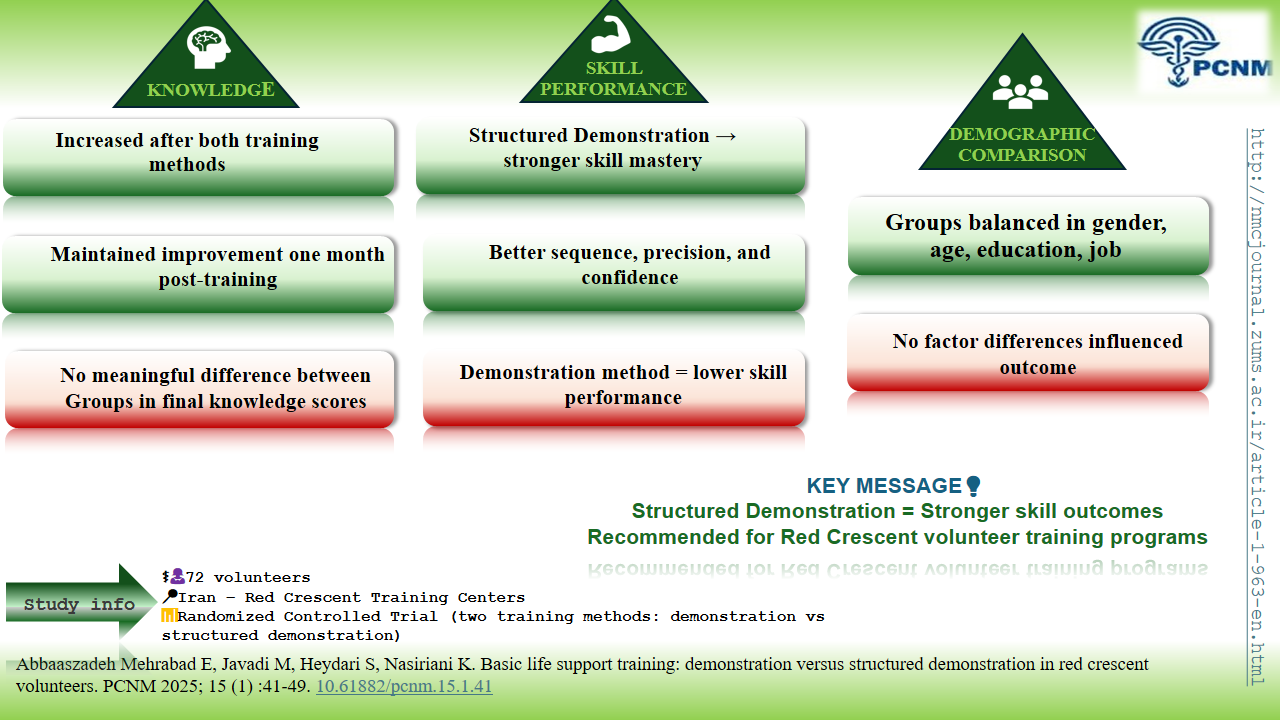

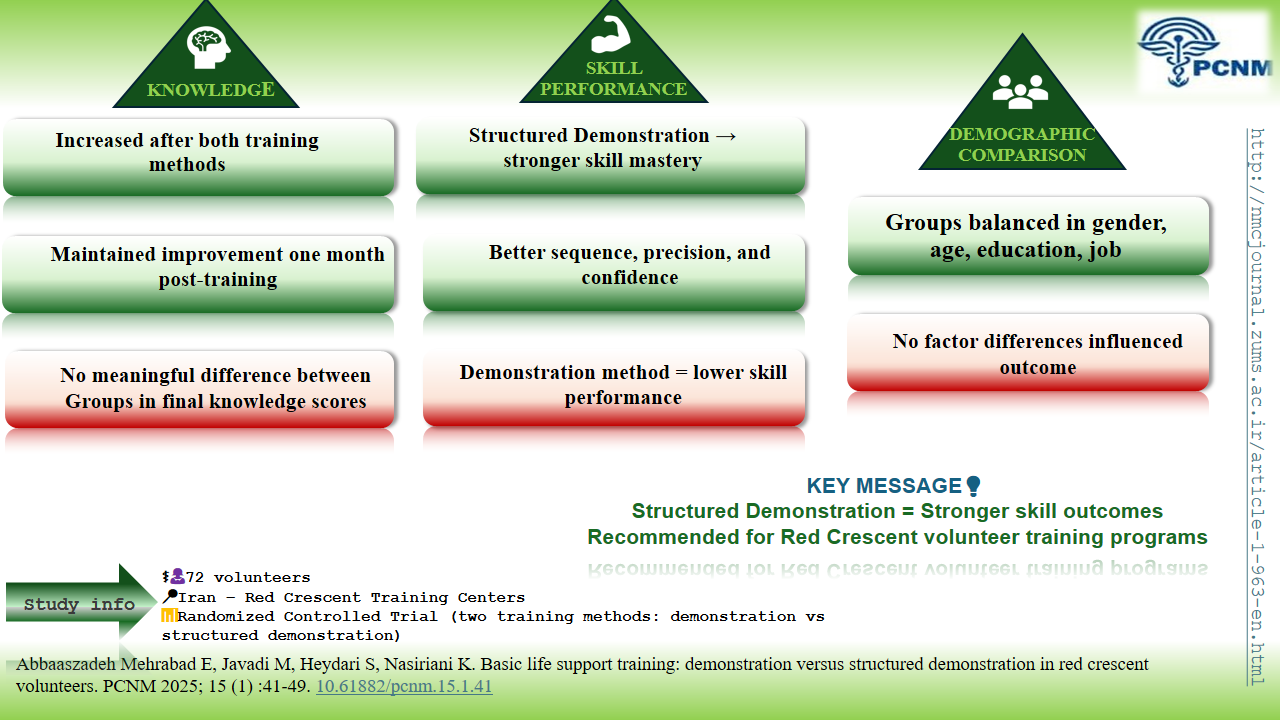

Knowledge Translation Statement

Audience: First aid instructors, emergency training coordinators, and volunteer organization managers.

Structured demonstration training is superior to simple demonstration for developing practical CPR skills in volunteers, leading to significantly higher skill retention.

Implement structured demonstration in first aid programs, as its systematic approach (silent demo, commentary, and group practice) ensures better skill acquisition for lay responders.

In the Structured Demonstration training method, the mean score of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) knowledge significantly increased one month after the intervention (p<0.001). Similarly, the demonstration training method also showed a statistically significant positive effect on training outcomes one month post-intervention (p<0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the Average Score of Basic Life Support Knowledge in the Two Study Groups before and One Month after the Intervention

ms: Mean Squares; ss: Sum of Squares.

The covariance results indicated no significant difference in the post-test knowledge scores between the groups (F=1.65, p>0.05). Furthermore, the effect size (η, Eta) indicated that both the Structured Demonstration training method and the demonstration training method explained only 2% of the variance in CPR knowledge among the participants, which is statistically insignificant. One month after the intervention, the mean score for CPR skills using the Structured Demonstration training method was significantly higher than that of the Demonstration training method (p = 0.001)(Table 4).

Table 4: Comparison of the Mean Score of Basic Life Support Skills in the Two Study Groups One Month after the Intervention

*Independent t test

Knowledge Translation Statement

Audience: First aid instructors, emergency training coordinators, and volunteer organization managers.

Structured demonstration training is superior to simple demonstration for developing practical CPR skills in volunteers, leading to significantly higher skill retention.

Implement structured demonstration in first aid programs, as its systematic approach (silent demo, commentary, and group practice) ensures better skill acquisition for lay responders.

Full-Text: (8 Views)

Introduction

Cardiac arrest is defined as the loss of cardiac function and systemic circulation [1]. One significant consequence of a heart attack is sudden cardiac arrest, which contributes to a substantial number of mortality cases [2]. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is a global public health issue [3]. Survival rates for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest are notably low, with only a few patients surviving [4,5]. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is a structured procedure performed on individuals experiencing cardiopulmonary arrest, aimed at maintaining circulation and respiration while providing adequate oxygen to vital organs to sustain life [6]. Initiating resuscitation efforts within four minutes of cardiac arrest can increase the likelihood of survival by two to four times [7]. Recent resuscitation guidelines have proposed strategies to improve the quality of CPR, such as adjusting the frequency and depth of chest compressions and ensuring complete release between compressions to improve the survival rate of victims [8]. Performing CPR before the arrival of emergency responders can prevent the transition of cardiac rhythms, such as ventricular fibrillation, to a systole, thereby preserving heart and brain function and enhancing survival chances [9]. Addressing this persistent issue requires adherence to established scientific principles and a high level of skill among responders [10]. Individuals who have received proper training in both basic and advanced life support (BLS) typically administer the most effective CPR [11]. Retaining knowledge and skills related to CPR is essential for an individual’s ability to respond competently when required. Therefore, it is imperative to organize training programs in a manner that maximizes skill acquisition [12]. Unfortunately, numerous reports indicate that the quality of CPR is often compromised due to inadequacies in the execution of resuscitation techniques [8]. It is crucial to utilize diverse teaching methods to enhance skills such as CPR [13].

Effective training is essential for improving survival outcomes following cardiac arrest [14]. Although resuscitators are familiar with contemporary CPR techniques, the quality of skill execution is often inadequate, which negatively impacts patient survival rates [15]. Successful CPR outcomes in individuals depend on effective collaboration among community members, emergency medical services, and hospital personnel. Therefore, immediate and adequate CPR provided by bystanders is a crucial link in the survival chain [16]. The Red Cross continuously recruits individuals from various age groups and diverse educational, social, economic, and cultural backgrounds to provide training in basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Engaging and training volunteers can be beneficial not only in normal conditions but also during crises [17].

Various training methods are available for developing CPR knowledge and skills within this group, including lectures, videos, and demonstrations [18]. In our country, the Red Crescent Organization employs demonstration training on BLS manikins as the conventional method for teaching cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The demonstration method effectively imparts clinical skills. In this approach, a faculty clinician serves as an instructor, directly transferring knowledge and skills to learners through hands-on practice with mannequins [19]. However, this method has limitations. Hansen et al. (2020) showed that there was no statistically significant difference in the pass rate when comparing a demonstration with a lecture for introducing BLS/AED [20]. Additionally, Muhajir (2020) indicated that the demonstration method can be time-consuming and does not reduce the trainer's workload during clinical instruction [21].

One effective method in Structured Demonstration training involves a systematic approach that includes a brief overview, silent demonstration, demonstration with commentary, oral presentation, individual practice, and group practice. This structured approach is applied both theoretically and practically through various stages, culminating in group practice for learners. Such methods enhance skill retention and long-term recall [22,23]. The structured approach clearly delineates the instructor’s role, providing explicit instructions at each stage to improve the learning process. It emphasizes a detailed educational framework in which the instructor facilitates learning [24]. Additionally, this training method prepares learners for teamwork in clinical settings [25]. A positive attitude toward education, characterized by careful planning and design that considers individuals' personal and social circumstances, along with the appropriate selection of educational methods and tools, can optimize the use of time and resources [26]. Given the importance of knowledge and performance in training community members and Red Crescent rescuers, further research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness and sustainability of the training provided.

Objectives

This study aims to compare the effects of CPR training using the Structured Demonstration method with those of a traditional demonstration method on the knowledge and skills of Red

Crescent volunteers.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This study was a randomized controlled trial (IRCT20231129060221N1) conducted in 2023. The research was carried out at the Red Crescent Training Unit in Abarkooh County, Yazd Province, Central Iran. This setting was equipped with dedicated facilities for theoretical instruction and a clinical skills laboratory. The practical components of basic life support (BLS) training were conducted in the skills lab using mannequin-based simulations.

Participants

Participants were selected through convenience sampling. Inclusion criteria consisted of active membership in the Red Crescent Society and literacy. Volunteers with prior experience in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) were excluded.

Sample Size

A sample size of 36 subjects per group was estimated based on the findings of Keegan et al. [27], considering a Type I error rate of 0.05, a test power of 90%, and an anticipated subject attrition rate of 10%. Ultimately, 72 individuals participated in the study (Figure 1).

Variables

The independent variable in this study was the teaching method, operationalized at two levels: the traditional demonstration method and the systematic structured demonstration method. The dependent variables (outcomes) were the participants' knowledge and practical skills related to basic life support (BLS) and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), measured before and one month after the intervention.

Procedures

The researcher visited the study site with an introductory letter. A comprehensive list of all Red Crescent volunteers was compiled. Participants were provided with general information regarding the research objectives, methodology, and duration. They were assured of anonymity, confidentiality, voluntary participation, and the right to withdraw at any time without consequence.

Written informed consent was obtained. Participants completed a demographic characteristics questionnaire and a pre-test assessing their CPR knowledge. Random assignment to one of the two intervention groups (Structured Demonstration Training Method or Demonstration Training Method) was conducted using the RANDBETWEEN function in Excel.

Intervention

The principles and theories of CPR were initially presented to all participants through a standardized two-hour lecture utilizing educational PowerPoint presentations, followed by practical training. The instructor for both groups was the principal investigator, a graduate of the Emergency Medical Service course and a certified Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation instructor at the Red Crescent. The total duration of training was consistent across both groups (three hours), while the methodology for the practical skills training component differed between the groups.

Participants in the Demonstration Method Group received training as follows: A pre-test was administered. Subsequently, practical training was conducted using a mannequin, during which key teaching points were emphasized. Following the instructor's demonstration, all participants practiced CPR on the mannequin. The session encouraged questions, with the instructor addressing any uncertainties. This structured demonstration and practice session lasted 60 minutes. It was followed by an additional 60-minute session dedicated to individual practice, where participants worked in small groups of 4 to 5 learners per mannequin.

Participants in the Structured Demonstration Method Group received training through a systematic six-stage workshop conducted on the same day, following a pre-test. The stages were: 1) Brief Overview: The instructor motivated learners by outlining the core concepts and objectives of the skills. 2) Silent Demonstration: The instructor performed the practical skills without verbal commentary. 3) Demonstration with Commentary: The skill was demonstrated again, accompanied by interactive teaching and real-time feedback from the instructor. 4) Oral Presentation: Learners verbally articulated the steps of the skill to reinforce knowledge and understanding. 5) Practice: Learners practiced the skill under the direct supervision of the instructor, who provided immediate corrections to prevent the reinforcement of incorrect techniques. 6) Group Practice: Participants were organized into small groups of four to five members to perform collective exercises and collaboratively solve problems. The total duration of this structured, multi-stage training workshop was approximately 60 minutes, which included allocated time for discussion and practice within the small groups.

Data Collection Tools

The study utilized a Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) Knowledge Questionnaire and a CPR Skill Assessment Checklist. The Basic Life Support Knowledge Assessment Questionnaire, developed by Shabannia et al. (2021), consisted of 15 items covering essential CPR components. Each correct answer scored 1 point (total range: 0-15). Its reliability (Cronbach's α) was 0.78 [28].

A researcher-developed checklist evaluated basic life support skills, containing 16 binary items. Each correct performance scored 1 point (total range: 0-16). Content and face validity were established by 15 experts. Reliability was confirmed via intra-rater stability assessment (Cohen's kappa = 0.86).

Follow-up and Assessment

One month post-training, all participants were invited to complete the CPR Knowledge Questionnaire (post-test). Additionally, participants' CPR skills were assessed during a practical test on a mannequin using the checklist. The examiner, blinded to the group assignment of participants, evaluated one participant at a time.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, frequency, percentage) were calculated. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test confirmed normal distribution of variables. Inferential statistics included independent t-test, paired t-test, Fisher's exact test, chi-square, and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). A significance level of 0.05 was considered.

Results

A total of 72 qualified volunteers participated in the study, of which 33 males (46%) and 39 females (54%). The results of the chi-square test indicated no significant differences between the groups concerning gender, occupation, marital status, age, and education. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the mean age between the two groups. Additional qualitative characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1.

Cardiac arrest is defined as the loss of cardiac function and systemic circulation [1]. One significant consequence of a heart attack is sudden cardiac arrest, which contributes to a substantial number of mortality cases [2]. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is a global public health issue [3]. Survival rates for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest are notably low, with only a few patients surviving [4,5]. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is a structured procedure performed on individuals experiencing cardiopulmonary arrest, aimed at maintaining circulation and respiration while providing adequate oxygen to vital organs to sustain life [6]. Initiating resuscitation efforts within four minutes of cardiac arrest can increase the likelihood of survival by two to four times [7]. Recent resuscitation guidelines have proposed strategies to improve the quality of CPR, such as adjusting the frequency and depth of chest compressions and ensuring complete release between compressions to improve the survival rate of victims [8]. Performing CPR before the arrival of emergency responders can prevent the transition of cardiac rhythms, such as ventricular fibrillation, to a systole, thereby preserving heart and brain function and enhancing survival chances [9]. Addressing this persistent issue requires adherence to established scientific principles and a high level of skill among responders [10]. Individuals who have received proper training in both basic and advanced life support (BLS) typically administer the most effective CPR [11]. Retaining knowledge and skills related to CPR is essential for an individual’s ability to respond competently when required. Therefore, it is imperative to organize training programs in a manner that maximizes skill acquisition [12]. Unfortunately, numerous reports indicate that the quality of CPR is often compromised due to inadequacies in the execution of resuscitation techniques [8]. It is crucial to utilize diverse teaching methods to enhance skills such as CPR [13].

Effective training is essential for improving survival outcomes following cardiac arrest [14]. Although resuscitators are familiar with contemporary CPR techniques, the quality of skill execution is often inadequate, which negatively impacts patient survival rates [15]. Successful CPR outcomes in individuals depend on effective collaboration among community members, emergency medical services, and hospital personnel. Therefore, immediate and adequate CPR provided by bystanders is a crucial link in the survival chain [16]. The Red Cross continuously recruits individuals from various age groups and diverse educational, social, economic, and cultural backgrounds to provide training in basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Engaging and training volunteers can be beneficial not only in normal conditions but also during crises [17].

Various training methods are available for developing CPR knowledge and skills within this group, including lectures, videos, and demonstrations [18]. In our country, the Red Crescent Organization employs demonstration training on BLS manikins as the conventional method for teaching cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The demonstration method effectively imparts clinical skills. In this approach, a faculty clinician serves as an instructor, directly transferring knowledge and skills to learners through hands-on practice with mannequins [19]. However, this method has limitations. Hansen et al. (2020) showed that there was no statistically significant difference in the pass rate when comparing a demonstration with a lecture for introducing BLS/AED [20]. Additionally, Muhajir (2020) indicated that the demonstration method can be time-consuming and does not reduce the trainer's workload during clinical instruction [21].

One effective method in Structured Demonstration training involves a systematic approach that includes a brief overview, silent demonstration, demonstration with commentary, oral presentation, individual practice, and group practice. This structured approach is applied both theoretically and practically through various stages, culminating in group practice for learners. Such methods enhance skill retention and long-term recall [22,23]. The structured approach clearly delineates the instructor’s role, providing explicit instructions at each stage to improve the learning process. It emphasizes a detailed educational framework in which the instructor facilitates learning [24]. Additionally, this training method prepares learners for teamwork in clinical settings [25]. A positive attitude toward education, characterized by careful planning and design that considers individuals' personal and social circumstances, along with the appropriate selection of educational methods and tools, can optimize the use of time and resources [26]. Given the importance of knowledge and performance in training community members and Red Crescent rescuers, further research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness and sustainability of the training provided.

Objectives

This study aims to compare the effects of CPR training using the Structured Demonstration method with those of a traditional demonstration method on the knowledge and skills of Red

Crescent volunteers.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This study was a randomized controlled trial (IRCT20231129060221N1) conducted in 2023. The research was carried out at the Red Crescent Training Unit in Abarkooh County, Yazd Province, Central Iran. This setting was equipped with dedicated facilities for theoretical instruction and a clinical skills laboratory. The practical components of basic life support (BLS) training were conducted in the skills lab using mannequin-based simulations.

Participants

Participants were selected through convenience sampling. Inclusion criteria consisted of active membership in the Red Crescent Society and literacy. Volunteers with prior experience in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) were excluded.

Sample Size

A sample size of 36 subjects per group was estimated based on the findings of Keegan et al. [27], considering a Type I error rate of 0.05, a test power of 90%, and an anticipated subject attrition rate of 10%. Ultimately, 72 individuals participated in the study (Figure 1).

Variables

The independent variable in this study was the teaching method, operationalized at two levels: the traditional demonstration method and the systematic structured demonstration method. The dependent variables (outcomes) were the participants' knowledge and practical skills related to basic life support (BLS) and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), measured before and one month after the intervention.

Procedures

The researcher visited the study site with an introductory letter. A comprehensive list of all Red Crescent volunteers was compiled. Participants were provided with general information regarding the research objectives, methodology, and duration. They were assured of anonymity, confidentiality, voluntary participation, and the right to withdraw at any time without consequence.

Written informed consent was obtained. Participants completed a demographic characteristics questionnaire and a pre-test assessing their CPR knowledge. Random assignment to one of the two intervention groups (Structured Demonstration Training Method or Demonstration Training Method) was conducted using the RANDBETWEEN function in Excel.

Intervention

The principles and theories of CPR were initially presented to all participants through a standardized two-hour lecture utilizing educational PowerPoint presentations, followed by practical training. The instructor for both groups was the principal investigator, a graduate of the Emergency Medical Service course and a certified Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation instructor at the Red Crescent. The total duration of training was consistent across both groups (three hours), while the methodology for the practical skills training component differed between the groups.

Participants in the Demonstration Method Group received training as follows: A pre-test was administered. Subsequently, practical training was conducted using a mannequin, during which key teaching points were emphasized. Following the instructor's demonstration, all participants practiced CPR on the mannequin. The session encouraged questions, with the instructor addressing any uncertainties. This structured demonstration and practice session lasted 60 minutes. It was followed by an additional 60-minute session dedicated to individual practice, where participants worked in small groups of 4 to 5 learners per mannequin.

Participants in the Structured Demonstration Method Group received training through a systematic six-stage workshop conducted on the same day, following a pre-test. The stages were: 1) Brief Overview: The instructor motivated learners by outlining the core concepts and objectives of the skills. 2) Silent Demonstration: The instructor performed the practical skills without verbal commentary. 3) Demonstration with Commentary: The skill was demonstrated again, accompanied by interactive teaching and real-time feedback from the instructor. 4) Oral Presentation: Learners verbally articulated the steps of the skill to reinforce knowledge and understanding. 5) Practice: Learners practiced the skill under the direct supervision of the instructor, who provided immediate corrections to prevent the reinforcement of incorrect techniques. 6) Group Practice: Participants were organized into small groups of four to five members to perform collective exercises and collaboratively solve problems. The total duration of this structured, multi-stage training workshop was approximately 60 minutes, which included allocated time for discussion and practice within the small groups.

Data Collection Tools

The study utilized a Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) Knowledge Questionnaire and a CPR Skill Assessment Checklist. The Basic Life Support Knowledge Assessment Questionnaire, developed by Shabannia et al. (2021), consisted of 15 items covering essential CPR components. Each correct answer scored 1 point (total range: 0-15). Its reliability (Cronbach's α) was 0.78 [28].

A researcher-developed checklist evaluated basic life support skills, containing 16 binary items. Each correct performance scored 1 point (total range: 0-16). Content and face validity were established by 15 experts. Reliability was confirmed via intra-rater stability assessment (Cohen's kappa = 0.86).

Follow-up and Assessment

One month post-training, all participants were invited to complete the CPR Knowledge Questionnaire (post-test). Additionally, participants' CPR skills were assessed during a practical test on a mannequin using the checklist. The examiner, blinded to the group assignment of participants, evaluated one participant at a time.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, frequency, percentage) were calculated. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test confirmed normal distribution of variables. Inferential statistics included independent t-test, paired t-test, Fisher's exact test, chi-square, and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). A significance level of 0.05 was considered.

Results

A total of 72 qualified volunteers participated in the study, of which 33 males (46%) and 39 females (54%). The results of the chi-square test indicated no significant differences between the groups concerning gender, occupation, marital status, age, and education. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the mean age between the two groups. Additional qualitative characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison of Qualitative Demographic Variables of Red Crescent volunteers in Two Study Groups

| Variables | Structured Demonstration | Demonstration | p* | |||

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |||

| sex | female | 16 | 44.00 | 17 | 47.00 | 0.81* |

| male | 20 | 56.00 | 19 | 53.00 | ||

| Marital status | married | 16 | 44.00 | 13 | 36.00 | 0.40* |

| single | 20 | 56.00 | 23 | 64.00 | ||

| Job | housewife | 19 | 55.00 | 20 | 55.00 | 1** |

| Employee | 5 | 14.00 | 4 | 11.00 | ||

| the student | 5 | 14.00 | 6 | 17.00 | ||

| freelance job | 7 | 17.00 | 6 | 17.00 | ||

| age | 20-30 | 18 | 51.00 | 26 | 76.00 | 0.13* |

| 31-40 | 12 | 32.00 | 6 | 17.00 | ||

| More than 41 | 6 | 17.00 | 4 | 7.00 | ||

| education | Less than a diploma | 16 | 42.42 | 8 | 22.00 | 0.13* |

| diploma | 10 | 27.27 | 16 | 44.00 | ||

| Higher education | 10 | 30.30 | 12 | 34.00 | ||

*Chi-Square Tests; **Fisher Exact Test; N=36 in each group

In the Structured Demonstration training method, the mean score of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) knowledge significantly increased one month after the intervention (p<0.001). Similarly, the demonstration training method also showed a statistically significant positive effect on training outcomes one month post-intervention (p<0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the Average Score of Basic Life Support Knowledge in the Two Study Groups before and One Month after the Intervention

| Group | Before intervention Mean (SD) |

One month after the intervention Mean (SD) |

t | p** |

| Structured Demonstration | 10.74(2.14) | 13.83(0.73) | -9.70 | <0.001 |

| Demonstration | 8.92(2.59) | 12.86(1.64) | -15.28 | <0.001 |

| t | 3.22 | 3.24 | ||

| p* | 0.002 | 0.002 |

*Independent t test; ** paired t test

The results of the independent t-test indicated a statistically significant difference between the two study groups before the intervention (p = 0.002). To control for baseline differences, a covariance analysis was conducted on the post-test knowledge results. The findings of this covariance analysis are presented in Table 3.

| Variable | Source | ss | df | ms | f | p | Etta |

| Knowledge score | intercept | 363.97 | 1 | 363.97 | 432.62 | <0.001 | 0.86 |

| Pre-test variable | 55.25 | 1 | 55.25 | 65.67 | <0.001 | 0.48 | |

| Group membership | 1.39 | 1 | 1.39 | 1.65 | 0.20 | 0.02 | |

| error | 58.05 | 69 | 0.84 | ||||

The covariance results indicated no significant difference in the post-test knowledge scores between the groups (F=1.65, p>0.05). Furthermore, the effect size (η, Eta) indicated that both the Structured Demonstration training method and the demonstration training method explained only 2% of the variance in CPR knowledge among the participants, which is statistically insignificant. One month after the intervention, the mean score for CPR skills using the Structured Demonstration training method was significantly higher than that of the Demonstration training method (p = 0.001)(Table 4).

Table 4: Comparison of the Mean Score of Basic Life Support Skills in the Two Study Groups One Month after the Intervention

| Group | Mean (SD) |

| Structured Demonstration | 14.38 (1.39) |

| Demonstration | 11.25 (2.34) |

| t | 6.89 |

| p * |

Discussion

The present study compared the effects of CPR training utilizing structured demonstration methods versus demonstration training methods on the knowledge and skills of basic life support among Red Crescent volunteers. The results indicated that both educational methods were effective in enhancing CPR knowledge. Therefore, based on the findings, teaching the theoretical issue of basic life support in both groups through lectures and slide presentations was accompanied by the acquisition of sufficient knowledge.

This result is consistent with the findings of other studies. Salehpoor-Emran et al. (2015) demonstrated that online basic CPR training, which included content explanations and slide presentations, improved the knowledge and practice of the Red Crescent Student Association volunteers [29]. Khademian et al. (2020) reported that basic CPR instruction, which included two hours of oral teaching through lectures, significantly enhanced the villagers’ knowledge of basic CPR [30]. Gurung et al. concluded that a structured teaching program significantly increased CPR knowledge among B.Sc. Nursing students at Dayananada Sagar [31]. Shabannia et al. (2021) found that both mannequin training and video training could enhance staff awareness of CPR [28]. This finding aligns with the study by Meenakshisundaram et al. (2023), which observed an improvement in CPR knowledge post-training through lecture-based teaching among school-going adolescents [18]. Neelima et al. (2016) demonstrated that a demonstration on basic life support (BLS) was effective in improving the knowledge of family members of adult patients at high risk of cardiopulmonary arrest [32].

Therefore, based on the findings of the present study and previous research, CPR training in various ways, which is basically accompanied by explanation and demonstration of content, is associated with increasing knowledge in the area of basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). The literature review indicates that most studies have focused on students or healthcare professionals. In contrast, the current study examined Red Crescent volunteers, who lack specialized education in healthcare. Enhancing their knowledge and skills demonstrates the effectiveness of CPR training within this group. Furthermore, this training increases community preparedness for emergency situations, including natural and man-made disasters. Additionally, these volunteers can disseminate basic life support knowledge within their families and communities, ultimately improving survival rates in cardiac arrest situations. Another noteworthy finding from our study was that, one month after the intervention, the mean skill score in the Structured Demonstration training was higher than that in the demonstration-training group. Khademian et al (2020) stated that basic teaching of CPR, which included demonstration, practice on a manikin, provision of feedback, and correction of errors, revealed that these methods could enhance the villagers’ performance of basic CPR techniques [30]. This intervention corresponds with the outcomes reported by Kim and Ahn (2019), who declared that the 5-step method of infant CPR training for nursing students was effective in improving performance abilities in a sustained manner and promoting a positive attitude among the groups both one week and six months after training [33].

Neelima et al. (2016) demonstrated that mannequin demonstrations of Basic Life Support (BLS) were effective in improving the skills of family members of adult patients at high risk of cardiopulmonary arrest [32].

In explaining the findings, it can be concluded that the significant skill improvement observed in the structured training group may be attributed to its comprehensive design, which includes several stages: a brief overview, silent demonstration, demonstration with commentary, oral presentation, individual practice, and group practice. This structured approach effectively integrates theoretical and practical content at various stages, culminating in group practice and feedback, which enhances retention in the learners' minds. One of the strengths of this study is that it represents the first interventional effort to compare the effects of basic life support training using structured demonstration and demonstration methods on the knowledge and skills of Red Crescent volunteers in Iran, marking an innovative contribution to the field. However, one limitation of the present study is that knowledge was assessed one-month post-intervention. To investigate the long-term retention of the material, future studies should employ a broader time frame for evaluation.

Conclusion

Based on the findings, both group demonstration and structured demonstration training methods were effective in increasing knowledge of performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The skill scores of participants in the structured group training method were higher than those in the group demonstration method, resulting in improved cardiopulmonary support skills among Red Crescent volunteers. Therefore, it is recommended to utilize both methods, particularly the structured demonstration method, in training the public and Red Crescent volunteers as first-line responders in the treatment of cardiac arrest.

Ethical Consideration

In adherence to ethical guidelines as per the Declaration of Helsinki, all ethical provisions were observed throughout the study. Participants provided informed consent to partake, ensuring confidentiality and anonymity of personal information. They were also informed of their right to withdraw at any point during the study.

The study protocol received approval from the Committee of Ethics in Human Research at Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran(Code: IR.SSU.REC.1402.024). The study has been registered with the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials under the code: IRCT20231129060221N1.

Acknowledgments

This study is the result of a research thesis supported by Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences. The researchers would like to express their gratitude to the Red Crescent volunteers who participated in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Funding

The researchers sincerely appreciate the financial support from Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran (code 15669). The funders played no role in the study's design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation. The authors will provide the final report of the study’s findings to the funders upon completion.

Authors' Contributions

Abbaszadeh Mehrabadi E., Javadi M., Heydari S., and Nasiriani K. conceptualized and designed the study.

Abbaszadeh Mehrabadi E. collected the data, while Javadi M. and Abbaszadeh Mehrabadi E. conducted the data analysis.

All authors contributed to manuscript preparation and approved the final version.

Artificial Intelligence Utilization

The authors declare that no generative AI technologies were used in the creation of this manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The present study compared the effects of CPR training utilizing structured demonstration methods versus demonstration training methods on the knowledge and skills of basic life support among Red Crescent volunteers. The results indicated that both educational methods were effective in enhancing CPR knowledge. Therefore, based on the findings, teaching the theoretical issue of basic life support in both groups through lectures and slide presentations was accompanied by the acquisition of sufficient knowledge.

This result is consistent with the findings of other studies. Salehpoor-Emran et al. (2015) demonstrated that online basic CPR training, which included content explanations and slide presentations, improved the knowledge and practice of the Red Crescent Student Association volunteers [29]. Khademian et al. (2020) reported that basic CPR instruction, which included two hours of oral teaching through lectures, significantly enhanced the villagers’ knowledge of basic CPR [30]. Gurung et al. concluded that a structured teaching program significantly increased CPR knowledge among B.Sc. Nursing students at Dayananada Sagar [31]. Shabannia et al. (2021) found that both mannequin training and video training could enhance staff awareness of CPR [28]. This finding aligns with the study by Meenakshisundaram et al. (2023), which observed an improvement in CPR knowledge post-training through lecture-based teaching among school-going adolescents [18]. Neelima et al. (2016) demonstrated that a demonstration on basic life support (BLS) was effective in improving the knowledge of family members of adult patients at high risk of cardiopulmonary arrest [32].

Therefore, based on the findings of the present study and previous research, CPR training in various ways, which is basically accompanied by explanation and demonstration of content, is associated with increasing knowledge in the area of basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). The literature review indicates that most studies have focused on students or healthcare professionals. In contrast, the current study examined Red Crescent volunteers, who lack specialized education in healthcare. Enhancing their knowledge and skills demonstrates the effectiveness of CPR training within this group. Furthermore, this training increases community preparedness for emergency situations, including natural and man-made disasters. Additionally, these volunteers can disseminate basic life support knowledge within their families and communities, ultimately improving survival rates in cardiac arrest situations. Another noteworthy finding from our study was that, one month after the intervention, the mean skill score in the Structured Demonstration training was higher than that in the demonstration-training group. Khademian et al (2020) stated that basic teaching of CPR, which included demonstration, practice on a manikin, provision of feedback, and correction of errors, revealed that these methods could enhance the villagers’ performance of basic CPR techniques [30]. This intervention corresponds with the outcomes reported by Kim and Ahn (2019), who declared that the 5-step method of infant CPR training for nursing students was effective in improving performance abilities in a sustained manner and promoting a positive attitude among the groups both one week and six months after training [33].

Neelima et al. (2016) demonstrated that mannequin demonstrations of Basic Life Support (BLS) were effective in improving the skills of family members of adult patients at high risk of cardiopulmonary arrest [32].

In explaining the findings, it can be concluded that the significant skill improvement observed in the structured training group may be attributed to its comprehensive design, which includes several stages: a brief overview, silent demonstration, demonstration with commentary, oral presentation, individual practice, and group practice. This structured approach effectively integrates theoretical and practical content at various stages, culminating in group practice and feedback, which enhances retention in the learners' minds. One of the strengths of this study is that it represents the first interventional effort to compare the effects of basic life support training using structured demonstration and demonstration methods on the knowledge and skills of Red Crescent volunteers in Iran, marking an innovative contribution to the field. However, one limitation of the present study is that knowledge was assessed one-month post-intervention. To investigate the long-term retention of the material, future studies should employ a broader time frame for evaluation.

Conclusion

Based on the findings, both group demonstration and structured demonstration training methods were effective in increasing knowledge of performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The skill scores of participants in the structured group training method were higher than those in the group demonstration method, resulting in improved cardiopulmonary support skills among Red Crescent volunteers. Therefore, it is recommended to utilize both methods, particularly the structured demonstration method, in training the public and Red Crescent volunteers as first-line responders in the treatment of cardiac arrest.

Ethical Consideration

In adherence to ethical guidelines as per the Declaration of Helsinki, all ethical provisions were observed throughout the study. Participants provided informed consent to partake, ensuring confidentiality and anonymity of personal information. They were also informed of their right to withdraw at any point during the study.

The study protocol received approval from the Committee of Ethics in Human Research at Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran(Code: IR.SSU.REC.1402.024). The study has been registered with the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials under the code: IRCT20231129060221N1.

Acknowledgments

This study is the result of a research thesis supported by Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences. The researchers would like to express their gratitude to the Red Crescent volunteers who participated in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Funding

The researchers sincerely appreciate the financial support from Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran (code 15669). The funders played no role in the study's design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation. The authors will provide the final report of the study’s findings to the funders upon completion.

Authors' Contributions

Abbaszadeh Mehrabadi E., Javadi M., Heydari S., and Nasiriani K. conceptualized and designed the study.

Abbaszadeh Mehrabadi E. collected the data, while Javadi M. and Abbaszadeh Mehrabadi E. conducted the data analysis.

All authors contributed to manuscript preparation and approved the final version.

Artificial Intelligence Utilization

The authors declare that no generative AI technologies were used in the creation of this manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Type of Study: Orginal research |

Subject:

Nursing

References

1. 1. Myat A, Song K-J, Rea T. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: current concepts. The Lancet. 2018;391(10124):970-9. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30472-0] [PMID]

2. Wong CX, Brown A, Lau DH, Chugh SS, Albert CM, Kalman JM, et al. Epidemiology of sudden cardiac death: global and regional perspectives. Heart, Lung And Circulation. 2019;28(1):6-14. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2018.08.026] [PMID]

3. Oliveira NC, Oliveira H, Silva TL, Boné M, Bonito J. The role of bystander CPR in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: what the evidence tells us. Hellenic Journal Of Cardiology. 2025;82:86-98. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjc.2024.09.002] [PMID]

4. Amacher SA, Bohren C, Blatter R, Becker C, Beck K, Mueller J, et al. Long-term survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiology. 2022;7(6):633-43. [https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2022.0795] [PMID]

5. Høybye M, Stankovic N, Holmberg M, Christensen HC, Granfeldt A, Andersen LW. In-hospital vs. out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: patient characteristics and survival. Resuscitation. 2021;158:157-65. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.11.016] [PMID]

6. Panchal AR, Berg KM, Hirsch KG, Kudenchuk PJ, Del Rios M, Cabañas JG, et al. 2019 American Heart Association focused update on advanced cardiovascular life support: use of advanced airways, vasopressors, and extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation during cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2019;140(24):e881-94. [https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000732]

7. Fernando SM, Tran A, Cheng W, Rochwerg B, Taljaard M, Vaillancourt C, et al. Pre-arrest and intra-arrest prognostic factors associated with survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;367. [https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6373] [PMID]

8. Nolan JP, Berg RA, Andersen LW, Bhanji F, Chan PS, Donnino MW, et al. Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: update of the Utstein resuscitation registry template for in-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2019;140(18):e746-57. [https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000710]

9. Shetty K, Roma M, Shetty M. Knowledge and awareness of basic life support among interns of a dental college in Mangalore, India. Indian Journal Of Public Health Research And Development. 2018;9(8):124-8. [https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-5506.2018.00708.8]

10. Cheng A, Nadkarni VM, Mancini MB, Hunt EA, Sinz EH, Merchant RM, et al. Resuscitation education science: educational strategies to improve outcomes from cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2018;138(6):e82-122. [https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000583]

11. González-Salvado V, Rodríguez-Ruiz E, Abelairas-Gómez C, Ruano-Raviña A, Peña-Gil C, González-Juanatey JR, et al. Training adult laypeople in basic life support: a systematic review. Revista Española De Cardiología (English Edition). 2020;73(1):53-68. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2018.11.013]

12. Halm M, Crespo C. Acquisition and retention of resuscitation knowledge and skills: what's practice have to do with it? American Journal Of Critical Care. 2018;27(6):513-7. [https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2018259] [PMID]

13. Gönenç IM, Aker MN, Şen YÇ. Examination of the effect of different techniques in teaching the management of shoulder dystocia: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Simulation In Nursing. 2024;96:101611. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2024.101611]

14. Magid DJ, Aziz K, Cheng A, Hazinski MF, Hoover AV, Mahgoub M, et al. Part 2: evidence evaluation and guidelines development: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020;142(16 Suppl 2):S358-65. [https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000898]

15. Sabeghi H, Mogharab M, Farajzadehz Z, Moghaddam EA. Effects of near-peer CPR workshop on medical students' knowledge and satisfaction. Research And Development In Medical Education. 2021;10(1):9-. [https://doi.org/10.34172/rdme.2021.009]

16. Wu Z, Panczyk M, Spaite DW, Hu C, Fukushima H, Langlais B, et al. Telephone cardiopulmonary resuscitation is independently associated with improved survival and functional outcome. Resuscitation. 2018;122:135-40. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.07.016] [PMID]

17. Rezaei P, Safari Moradabadi A, Montazerghaem H, Miri HR, Paknahad A, Alavi A. Comparing two training methods, traditional CPR skill and distance training at the Red Crescent Organization in Hormozgan Province. Life Science Journal. 2013;10(9):140-5. [http://www.lifesciencesite.com]

18. Meenakshisundaram R, Ramavel AR, Banu N, Areeb A, Premkumar EMJ, Saeed S. Effectiveness of teaching and demonstration in improvement of knowledge and skill on CPR among school-going adolescents: a quasi-experimental study. National Journal Of Emergency Medicine SEMI. 2023;1(1):18-22. [https://doi.org/10.5005/njem-11015-0009]

19. Nurul AAC, Silvy IM. The effectiveness of demonstration methods on the skills of adolescents as bystander CPR. Biotika. 2019;2(27):3-8. [https://agris.fao.org/search/ar/records/67598ce87b9a06a08f081ad5]

20. Hansen C, Bang C, Rasmussen SE, Nebsbjerg MA, Lauridsen KG, Bomholt KB, et al. Basic life support training: demonstration versus lecture - a randomised controlled trial. The American Journal Of Emergency Medicine. 2020;38(4):720-6. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.06.008] [PMID]

21. Muhajir A. The application of demonstration methods in learning explanation text middle school students: class action research. AlAdzkiya International Of Education And Social (AIoES) Journal. 2020;1(2):60-8. [https://doi.org/10.55311/aioes.v1i2.25]

22. Ahmad N, Musa M, Kadir F, Sharizman S, Hidrus A, Hassan H, et al. Exploring the functionality of technology-driven CPR training methodologies among healthcare practitioners: a randomized control pilot study. Journal Of The Saudi Heart Association. 2024;36(2):99. [https://doi.org/10.37616/2212-5043.1382] [PMID]

23. da Silva AA, de Melo Lanzoni GM, de Sousa LP, Barra DCC, Lazzari DD, do Nascimento KC. Development of a cardiopulmonary resuscitation prototype for health education. Revista De Enfermagem UERJ. 2020;28:e53033:1-7. [https://doi.org/10.12957/reuerj.2020.53033]

24. Pivač S, Gradišek P, Skela-Savič B. The impact of cardiopulmonary resuscitation training on schoolchildren and their CPR knowledge, attitudes toward CPR, and willingness to help others. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1-11. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09072-y] [PMID]

25. Balan P, Maritz A, McKinlay M. A structured method for innovating in entrepreneurship pedagogies. Education And Training. 2018;60(7/8):819-40. [https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-05-2017-0064]

26. Silverplats J, Strömsöe A, Äng B, Södersved Källestedt M-L. Attitudes towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation situations and associations with potential influencing factors-a survey among in-hospital healthcare professionals. PLOS One. 2022;17(7):e0271686. [https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0271686] [PMID]

27. Keegan D, Heffernan E, McSharry J, Barry T, Masterson S. Identifying priorities for the collection and use of data related to community first response and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: protocol for a nominal group technique study. HRB Open Research. 2021;4(81):1-11. [https://doi.org/10.12688/hrbopenres.13347.1] [PMID]

28. Shabannia A, Pirasteh A, Jouhari Z. The effectiveness of cardiopulmonary resuscitation training by mannequin and educational video on awareness of Shahed University staff. Daneshvar Medicine. 2021;29(4):33-41. [https://doi.org/10.22070/daneshmed.2021.14976.1109]

29. Salehpoor-Emran M, Pashaeypoor S, Majdabadi ZA, Böttiger BW, Poortaghi S, Haghani S. The effect of online CPR training on the knowledge and practice of Red Crescent student association volunteers during COVID-19 pandemic: a randomized clinical trial study. Resuscitation Plus. 2025:101010. [https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5205014]

30. Khademian Z, Hajinasab Z, Mansouri P. The effect of basic CPR training on adults' knowledge and performance in rural areas of Iran: a quasi-experimental study. Open Access Emergency Medicine. 2020:27-34. [https://doi.org/10.2147/OAEM.S227750] [PMID]

31. Gurung P, Mishra S, Chandrakar K. A pre-experimental study to assess the effectiveness of STP on knowledge regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation among B.Sc. nursing students. Galore International Journal Of Health Sciences And Research. 2020;5:35-40. [http://www.gijhsr.com]

32. Neelima R, Gopichandran L, Kumar BD, Devagourou V, Sanjeev B. A comparative study to evaluate the effectiveness of mannequin demonstration versus video teaching programme on basic life support to family members of adult patients. International Journal Of Nursing Education. 2016;8(4):142-7. [https://doi.org/10.5958/0974-9357.2016.00141.0]

33. Kim JY, Ahn HY. The effects of the 5-step method for infant cardiopulmonary resuscitation training on nursing students' knowledge, attitude, and performance ability. Child Health Nursing Research. 2019;25(1):17-27. [https://doi.org/10.4094/chnr.2019.25.1.17] [PMID]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |