Preventive Care in Nursing and Midwifery Journal

Volume 15, Issue 3 (10-2025)

Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J 2025, 15(3): 80-90 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.LARUMS.REC.1402.016

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Bazrafshan M, Barghi O, Mansouri A, modarresi M, Masmouei B. Policy insights into nutritional decision-making in individuals with metabolic syndrome: Implications for food labeling and dietary choices. Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J 2025; 15 (3) :80-90

URL: http://nmcjournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-993-en.html

URL: http://nmcjournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-993-en.html

Mohammad-Rafi Bazrafshan

, Omid Barghi

, Omid Barghi

, Amir Mansouri

, Amir Mansouri

, MohammadJavad Modarresi

, MohammadJavad Modarresi

, Behnam Masmouei *

, Behnam Masmouei *

, Omid Barghi

, Omid Barghi

, Amir Mansouri

, Amir Mansouri

, MohammadJavad Modarresi

, MohammadJavad Modarresi

, Behnam Masmouei *

, Behnam Masmouei *

School of Nursing Hazrat Zahra (P.B.U.H) Abadeh, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. , behnam.masmouei@gmail.com

Keywords: Metabolic Syndrome, Food Labeling, Nutritional Decision-Making, Qualitative Study, Policy Brief

Full-Text [PDF 802 kb]

(94 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (145 Views)

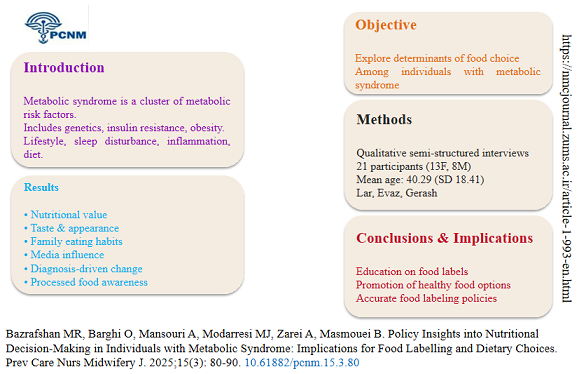

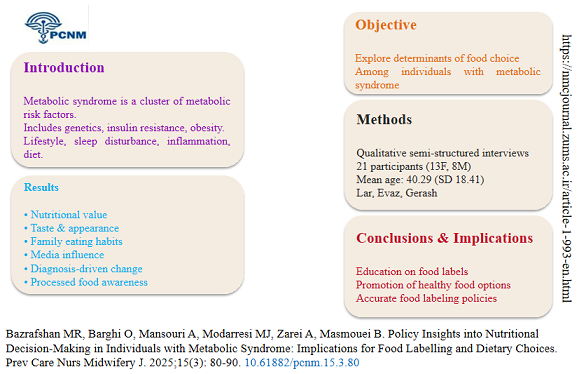

Data analysis from the 21 participants with metabolic syndrome resulted in the identification of 26 distinct, yet interrelated, determinants of food choice. These determinants were comprehensively categorized into seven core domains: (1) health and nutrition factors, (2) personal preferences, (3) information and label use, (4) label literacy and understanding, (5) economic constraints, (6) external influences, and (7) policy and oversight. This refined framework elaborates on established models by explicitly distinguishing between the external tool of label use and the internal capacity of label literacy. A detailed presentation of all 26 themes, including direct participant quotes that illustrate each theme, is provided in Table 2. This table offers a granular view of the qualitative data, capturing the nuanced perspectives of the participants. The relationships between these seven domains, the identified challenges, and the corresponding policy recommendations are further illustrated in Figure 1. Thus, Table 3 and Figure 1 work in tandem, with the table providing the empirical evidence and the figure mapping the conceptual relationships and pathways for intervention.

These findings are intended to support public health nutrition interventions, strengthen food labeling systems, and promote healthier dietary decision-making among at-risk groups.

Table 2. Nutritional Decision-Making in Individuals with Metabolic Syndrome and Policy Recommendations

Table 3. Comprehensive of Themes and Participant Quotes on Nutritional Decision-Making in Individuals with Metabolic Syndrome

Food labeling emerged as a particularly salient theme. Although participants expressed strong support for front-of-package (FOP) nutrition indicators, they simultaneously voiced concerns about the accuracy and trustworthiness of these labels. This duality mirrors findings from Brazil and South Korea, where clear, credible FOP labeling systems have been shown to positively influence consumer behavior and mitigate diet-related health risks [28-31].

Educational attainment also surfaced as a critical determinant of nutritional label utilization and subsequent food selection, with this relationship especially pronounced among female participants [29].

Although the present study did not explicitly examine regional foods such as seaweeds or tropical fruits, existing literature suggests that these foods may play a protective role against metabolic risk factors [32].

Policy Recommendations

1. Develop targeted nutrition education programs for individuals with metabolic syndrome [21, 30, 31].

Recommendation: Implement evidence-based educational campaigns and community workshops emphasizing label interpretation, metabolic syndrome awareness, and informed dietary choices.

Responsible Entities:

Recommendation: Mandate a unified, color-coded Front-of-Package Labeling (FoPL) system (e.g., traffic-light format) for all processed foods, supported by a robust auditing mechanism to verify health claims.

Responsible Entities:

Recommendation: Provide targeted subsidies for essential healthy foods and expand farmers' markets or “healthy food zones” in underserved areas.

Responsible Entities:

Recommendation: Restrict advertising of foods high in salt, sugar, and unhealthy fats during peak viewing hours and require digital influencers to include clear health warnings when promoting such products.

Responsible Entities:

Recommendation: Introduce a government-endorsed “Healthy Choice” certification seal and offer financial incentives for product reformulation to improve nutritional quality.

Responsible Entities:

Recommendation: Establish a “National Committee for Healthy Nutrition” to coordinate cross-sector policies following a Health-in-All-Policies approach.

Responsible Entities:

Recommendation: Allocate research funding for clinical trials evaluating the effects of indigenous foods and integrate findings into culturally relevant dietary guidelines.

Responsible Entities:

• Vice-Presidency for Science and Technology & Ministry of Health

• Regional Universities of Medical Sciences & Research Institutes of Medicinal Plants

• Ministry of Agriculture

Transferability of Findings

The transferability of these findings should be interpreted with caution. Because the study sample was drawn from a limited geographical area, broader application of the results may be constrained.

Conclusion

The lived experiences of individuals with metabolic syndrome reveal a complex web of nutritional, economic, informational, and policy-related influences.

Addressing these factors requires coordinated action across education, regulation, and public engagement. Without informed and proactive policy measures, the burden of metabolic syndrome will continue to rise, undermining long-term health outcomes and straining healthcare systems [21-33].

Ethical Considerations

The Ethics Committee of Larestan University of Medical Sciences approved this study (IR.LARUMS.REC.1402.016), and participants provided written informed consent.

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to thank the Larestan University of Medical Sciences for their financial support of this research (Project No.1401-141). We also sincerely thank all the individuals who participated and cooperated in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

N/A

Authors' Contributions

Rafi Bezrafshan M.: contributed to the study design and supervision of the research process.

Masmouei B.: was responsible for drafting and writing the manuscript.

Mansouri A.: carried out the data analysis.

Barghi O.: conducted the interviews and participated in data analysis.

Modarresi M.J.: contributed to the editing and revision of the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final version of the paper.

Artificial Intelligence Utilization for Article Writing

The authors utilized artificial intelligence tools for assistance in grammar checking and language polishing during the manuscript preparation process. The conceptualization, data analysis, interpretation of results, and critical revision of the intellectual content remain solely the responsibility of the authors.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to privacy and ethical considerations, the raw interview transcripts are not publicly available.

Knowledge Translation Statement

Audience: Public health nurses, clinical dietitians, primary care providers, and health policymakers

Policy-level tools, such as clear and comprehensible food labeling, are crucial for supporting individuals with metabolic Syndrome in making informed dietary choices. Integrating evidence-based nutritional guidance into straightforward labeling and public health messaging can empower patients and bridge the gap between clinical dietary advice and everyday food selection, thereby improving disease management and health outcomes.

Audience: Public health nurses, clinical dietitians, primary care providers, and health policymakers

Policy-level tools, such as clear and comprehensible food labeling, are crucial for supporting individuals with metabolic Syndrome in making informed dietary choices. Integrating evidence-based nutritional guidance into straightforward labeling and public health messaging can empower patients and bridge the gap between clinical dietary advice and everyday food selection, thereby improving disease management and health outcomes.

Full-Text: (2 Views)

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome is characterized by a cluster of interrelated metabolic risk factors, including abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia, reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels, hypertension, and insulin resistance. This constellation of factors collectively elevates the risk for developing cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus [1]. The term "syndrome" is derived from the Greek word for "concurrence" or "running together." In medical terminology, it denotes a group of symptoms and signs that collectively characterize a specific disease or pathological state [2].

While the precise etiology of metabolic syndrome remains incompletely understood, recent research has identified several contributing factors, including genetic predisposition, insulin resistance, adverse lifestyle habits, sleep disturbances, chronic inflammation, prenatal and neonatal complications, circadian rhythm disruption, and obesity [3]. Obesity, known as one of the causes of metabolic syndrome, is associated with an increase in adipose tissue. This adipose tissue acts as a major endocrine organ, and by secreting some substances, it creates the basis for the occurrence of this syndrome. Abdominal obesity, usually characterized by an increase in waist diameter, can be a characteristic of this syndrome [4, 5]. Obesity, particularly abdominal adiposity, constitutes a central pathogenic factor in metabolic Syndrome. Adipose tissue acts as an active endocrine organ, secreting a range of bioactive substances that promote a state of metabolic dysfunction. In Iran, obesity represents the second most prevalent metabolic disorder. The prevalence rates are alarming: abdominal obesity and hypertension affect 65.0% of women and 48.9% of men, while low HDL-C levels are observed in 92.7% of women and 81.8% of men [6].

Dietary modification is a key strategy for managing metabolic syndrome [1, 7]. The Mediterranean diet has been associated with reduced obesity and metabolic risk [8]. while consumption of saturated fats has been shown to increase abdominal obesity and insulin resistance in animal models [9].

Adherence to healthy eating patterns, such as those outlined in the Healthy Eating Index, can prevent obesity and related complications [10]. However, studies indicate poor adherence to the Mediterranean diet among children and adolescents in southern Europe, highlighting the need for targeted nutrition education [11].

Food labeling has emerged as a potential tool for guiding dietary choices. However, evidence regarding its efficacy remains inconsistent; while some studies indicate that nutrition labels can positively influence health outcomes, others report no significant effect on body mass index (BMI) [12]. Public engagement with nutrition labels remains limited. Furthermore, attention to nutritional information is strongly influenced by socioeconomic status and overall health status [13]. Furthermore, interpretive labeling systems, such as the traffic light scheme, may reduce the consumption of unhealthy food products by leveraging negative emotional responses, including fear or guilt [14].

Building on this evidence, individual perception of nutrition labels encompassing both numerical tables and interpretive front-of-pack indicators like the traffic light system is a critical determinant of dietary behavior.

Objectives

This study was designed to conduct a qualitative exploration of how individuals diagnosed with metabolic syndrome interpret and utilize food labels. The ultimate objective is to generate evidence-based insights that can inform effective public health policies and strategies aimed at facilitating healthier food choices within this at-risk population.

Methods

Study Design

A qualitative content analysis study was conducted, utilizing the conventional approach. In this approach, coding categories are derived directly and inductively from the raw data, without the imposition of pre-existing categories or theoretical frameworks [15].

Study Population and Sampling

The study population comprised patients diagnosed with metabolic syndrome who were attending community health centers in the cities of Lar, Evaz, and Gerash. A purposive sample was selected from this population based on the pre-defined inclusion criteria.

Inclusion Criteria

1. A confirmed medical diagnosis of metabolic syndrome in the patient's record.

Note on Diagnostic Criteria: Metabolic syndrome was defined according to the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP-ATP III) criteria, which is the most widely used standard in Iranian research. This requires the presence of at least three of the following five risk factors:

Metabolic syndrome is characterized by a cluster of interrelated metabolic risk factors, including abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia, reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels, hypertension, and insulin resistance. This constellation of factors collectively elevates the risk for developing cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus [1]. The term "syndrome" is derived from the Greek word for "concurrence" or "running together." In medical terminology, it denotes a group of symptoms and signs that collectively characterize a specific disease or pathological state [2].

While the precise etiology of metabolic syndrome remains incompletely understood, recent research has identified several contributing factors, including genetic predisposition, insulin resistance, adverse lifestyle habits, sleep disturbances, chronic inflammation, prenatal and neonatal complications, circadian rhythm disruption, and obesity [3]. Obesity, known as one of the causes of metabolic syndrome, is associated with an increase in adipose tissue. This adipose tissue acts as a major endocrine organ, and by secreting some substances, it creates the basis for the occurrence of this syndrome. Abdominal obesity, usually characterized by an increase in waist diameter, can be a characteristic of this syndrome [4, 5]. Obesity, particularly abdominal adiposity, constitutes a central pathogenic factor in metabolic Syndrome. Adipose tissue acts as an active endocrine organ, secreting a range of bioactive substances that promote a state of metabolic dysfunction. In Iran, obesity represents the second most prevalent metabolic disorder. The prevalence rates are alarming: abdominal obesity and hypertension affect 65.0% of women and 48.9% of men, while low HDL-C levels are observed in 92.7% of women and 81.8% of men [6].

Dietary modification is a key strategy for managing metabolic syndrome [1, 7]. The Mediterranean diet has been associated with reduced obesity and metabolic risk [8]. while consumption of saturated fats has been shown to increase abdominal obesity and insulin resistance in animal models [9].

Adherence to healthy eating patterns, such as those outlined in the Healthy Eating Index, can prevent obesity and related complications [10]. However, studies indicate poor adherence to the Mediterranean diet among children and adolescents in southern Europe, highlighting the need for targeted nutrition education [11].

Food labeling has emerged as a potential tool for guiding dietary choices. However, evidence regarding its efficacy remains inconsistent; while some studies indicate that nutrition labels can positively influence health outcomes, others report no significant effect on body mass index (BMI) [12]. Public engagement with nutrition labels remains limited. Furthermore, attention to nutritional information is strongly influenced by socioeconomic status and overall health status [13]. Furthermore, interpretive labeling systems, such as the traffic light scheme, may reduce the consumption of unhealthy food products by leveraging negative emotional responses, including fear or guilt [14].

Building on this evidence, individual perception of nutrition labels encompassing both numerical tables and interpretive front-of-pack indicators like the traffic light system is a critical determinant of dietary behavior.

Objectives

This study was designed to conduct a qualitative exploration of how individuals diagnosed with metabolic syndrome interpret and utilize food labels. The ultimate objective is to generate evidence-based insights that can inform effective public health policies and strategies aimed at facilitating healthier food choices within this at-risk population.

Methods

Study Design

A qualitative content analysis study was conducted, utilizing the conventional approach. In this approach, coding categories are derived directly and inductively from the raw data, without the imposition of pre-existing categories or theoretical frameworks [15].

Study Population and Sampling

The study population comprised patients diagnosed with metabolic syndrome who were attending community health centers in the cities of Lar, Evaz, and Gerash. A purposive sample was selected from this population based on the pre-defined inclusion criteria.

Inclusion Criteria

1. A confirmed medical diagnosis of metabolic syndrome in the patient's record.

Note on Diagnostic Criteria: Metabolic syndrome was defined according to the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP-ATP III) criteria, which is the most widely used standard in Iranian research. This requires the presence of at least three of the following five risk factors:

- Abdominal Obesity: Waist circumference ≥102 cm in men or ≥88 cm in women.

- Elevated Triglycerides: ≥150 mg/dL or ongoing drug treatment for hypertriglyceridemia.

- Reduced HDL-C: <40 mg/dL in men or <50 mg/dL in women or ongoing drug treatment for low HDL-C.

- Elevated Blood Pressure: Systolic pressure ≥130 mmHg or diastolic pressure ≥85 mmHg, or ongoing antihypertensive drug therapy.

- Elevated Fasting Glucose: ≥100 mg/dL or ongoing drug treatment for hyperglycemia [15].

2. Age of 18 years or older.

3. Willingness to provide voluntary informed consent to participate in the study.

4. Current residency within the catchment areas of Lar, Evaz, or Gerash.

5. Proficiency in the Persian language to ensure comprehension of interview questions.

6. Ability and willingness to articulate personal experiences related to food choices and labeling.

Exclusion Criteria

Voluntary withdrawal from the study at any stage of the research process.

Data Collection

Data were collected through semi-structured, in-depth interviews. This method utilizes open-ended questions to guide the conversation while allowing participants the freedom to elaborate extensively on their experiences. All interviews were audio-recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim to ensure the accurate capture of data for analysis [16]. The interview process commenced with a general, open-ended question. Subsequently, based on the participants' responses and the emerging themes relevant to the research objectives, more specific probing questions were introduced to deepen the exploration [17].

Following the provision of informed consent, the interview schedule and location were arranged by mutual agreement between the researcher and each participant. To ensure data integrity, all interviews were audio-recorded with the participant's permission, supplemented by the researcher's field notes. Upon concluding each session, participants were thanked, and the possibility of a follow-up interview was discussed. In this study, the interview process started by asking, "What information do you have about the food information label placed on the food?” Other questions were asked of the samples based on the interview process and study objectives. It tried to use exploratory questions such as "Can you explain more?" “Or "Can you give an example? It was used to collect deeper information.

Sampling and Recruitment

A purposive sampling strategy was employed to recruit individuals diagnosed with metabolic syndrome who provided informed consent. The sampling process continued until data saturation was achieved, which was defined as the point at which subsequent interviews yielded no new thematic insights or properties of the identified categories.

A single researcher conducted, audio-recorded, and managed all interviews to ensure consistency. A total of 21 participants were enrolled. After 19 interviews, the primary themes and patterns were consistently repeating, with no novel information emerging. Two further interviews were conducted to rigorously confirm that data saturation had been fully attained.

Data Analysis

Data collection and analysis were conducted concurrently, in accordance with the qualitative content analysis approach outlined by Graneheim and Lundman [18]. The recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim and managed using MAXQDA software (version 10). The analysis process involved multiple close readings of the transcripts. The text was then broken down into meaning units, which were subsequently condensed and abstracted into codes. These codes were grouped into sub-categories and categories based on their similarities and conceptual relationships, forming a comprehensive coding structure.

Rigor and Trustworthiness

All interviews were conducted by the principal investigator, who has training and experience in qualitative methodologies. To enhance the credibility of the findings, several strategies were employed. During data collection, the interviewer utilized neutral probing questions and practiced reflexivity to minimize personal bias. To ensure confirmability, the coding process was conducted independently by two researchers. Any discrepancies in coding were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached. Furthermore, the trustworthiness of the study was evaluated against the established criteria of Lincoln and Guba [19]. To ensure the credibility of the findings, several strategies were employed, including the researcher's prolonged engagement with the data, maintaining a reflective journal, and peer debriefing with qualitative research experts. Member checking was conducted by sharing initial codes and interpretations with participants to verify accuracy. To enhance dependability, purposive sampling aimed for maximum variation among participants. Finally, to establish transferability, thick, descriptive data are provided to allow readers to assess the applicability of the findings to other contexts.

Results

21 people participated in this study. The average age of the samples was 40.29 (18.41).

The demographic information of the samples is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Participants

3. Willingness to provide voluntary informed consent to participate in the study.

4. Current residency within the catchment areas of Lar, Evaz, or Gerash.

5. Proficiency in the Persian language to ensure comprehension of interview questions.

6. Ability and willingness to articulate personal experiences related to food choices and labeling.

Exclusion Criteria

Voluntary withdrawal from the study at any stage of the research process.

Data Collection

Data were collected through semi-structured, in-depth interviews. This method utilizes open-ended questions to guide the conversation while allowing participants the freedom to elaborate extensively on their experiences. All interviews were audio-recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim to ensure the accurate capture of data for analysis [16]. The interview process commenced with a general, open-ended question. Subsequently, based on the participants' responses and the emerging themes relevant to the research objectives, more specific probing questions were introduced to deepen the exploration [17].

Following the provision of informed consent, the interview schedule and location were arranged by mutual agreement between the researcher and each participant. To ensure data integrity, all interviews were audio-recorded with the participant's permission, supplemented by the researcher's field notes. Upon concluding each session, participants were thanked, and the possibility of a follow-up interview was discussed. In this study, the interview process started by asking, "What information do you have about the food information label placed on the food?” Other questions were asked of the samples based on the interview process and study objectives. It tried to use exploratory questions such as "Can you explain more?" “Or "Can you give an example? It was used to collect deeper information.

Sampling and Recruitment

A purposive sampling strategy was employed to recruit individuals diagnosed with metabolic syndrome who provided informed consent. The sampling process continued until data saturation was achieved, which was defined as the point at which subsequent interviews yielded no new thematic insights or properties of the identified categories.

A single researcher conducted, audio-recorded, and managed all interviews to ensure consistency. A total of 21 participants were enrolled. After 19 interviews, the primary themes and patterns were consistently repeating, with no novel information emerging. Two further interviews were conducted to rigorously confirm that data saturation had been fully attained.

Data Analysis

Data collection and analysis were conducted concurrently, in accordance with the qualitative content analysis approach outlined by Graneheim and Lundman [18]. The recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim and managed using MAXQDA software (version 10). The analysis process involved multiple close readings of the transcripts. The text was then broken down into meaning units, which were subsequently condensed and abstracted into codes. These codes were grouped into sub-categories and categories based on their similarities and conceptual relationships, forming a comprehensive coding structure.

Rigor and Trustworthiness

All interviews were conducted by the principal investigator, who has training and experience in qualitative methodologies. To enhance the credibility of the findings, several strategies were employed. During data collection, the interviewer utilized neutral probing questions and practiced reflexivity to minimize personal bias. To ensure confirmability, the coding process was conducted independently by two researchers. Any discrepancies in coding were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached. Furthermore, the trustworthiness of the study was evaluated against the established criteria of Lincoln and Guba [19]. To ensure the credibility of the findings, several strategies were employed, including the researcher's prolonged engagement with the data, maintaining a reflective journal, and peer debriefing with qualitative research experts. Member checking was conducted by sharing initial codes and interpretations with participants to verify accuracy. To enhance dependability, purposive sampling aimed for maximum variation among participants. Finally, to establish transferability, thick, descriptive data are provided to allow readers to assess the applicability of the findings to other contexts.

Results

21 people participated in this study. The average age of the samples was 40.29 (18.41).

The demographic information of the samples is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Participants

| Variable | Number | Percentage |

| Age |

| ≤40 | 13 | 61.9 |

| >40 | 8 | 38.1 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 8 | 38.1 |

| Female | 13 | 61.9 |

| Marital status | ||

| Sigel | 8 | 38.1 |

| Married | 13 | 61.9 |

| Level of Education | ||

| Below a diploma | 5 | 23.8 |

| Diploma | 6 | 28.6 |

| Academic | 10 | 47.6 |

| Job | ||

| Employee | 4 | 19 |

| Self-Employee | 5 | 23.8 |

| Unemployed | 5 | 23.8 |

| Housewife | 5 | 23.8 |

| Retired | 2 | 9.5 |

Data analysis from the 21 participants with metabolic syndrome resulted in the identification of 26 distinct, yet interrelated, determinants of food choice. These determinants were comprehensively categorized into seven core domains: (1) health and nutrition factors, (2) personal preferences, (3) information and label use, (4) label literacy and understanding, (5) economic constraints, (6) external influences, and (7) policy and oversight. This refined framework elaborates on established models by explicitly distinguishing between the external tool of label use and the internal capacity of label literacy. A detailed presentation of all 26 themes, including direct participant quotes that illustrate each theme, is provided in Table 2. This table offers a granular view of the qualitative data, capturing the nuanced perspectives of the participants. The relationships between these seven domains, the identified challenges, and the corresponding policy recommendations are further illustrated in Figure 1. Thus, Table 3 and Figure 1 work in tandem, with the table providing the empirical evidence and the figure mapping the conceptual relationships and pathways for intervention.

These findings are intended to support public health nutrition interventions, strengthen food labeling systems, and promote healthier dietary decision-making among at-risk groups.

Table 2. Nutritional Decision-Making in Individuals with Metabolic Syndrome and Policy Recommendations

| Category | Key Findings | Policy Recommendations |

| Health and Nutrition Factors | • Awareness of healthy foods • Disease-driven dietary changes • Concerns about processed foods |

• Promote nutrition education tailored to chronic conditions • Regulate processed food content and labeling |

| Personal Preferences | • Taste and appearance prioritized over health • Family dietary conflicts |

• Design culturally sensitive campaigns balancing taste and health • Support family-based nutrition programs |

| Information and Label Use | • Mixed understanding of labels • High attention to expiration dates • Skepticism about label accuracy |

• Simplify and standardize food labels • Ensure label accuracy through regulatory oversight • Improve public literacy on label use |

| Economic Constraints | • High cost of healthy foods • Price-driven consumer choices |

• Subsidize essential healthy food items • Promote affordable dietary alternatives in low-income areas |

| External Influences | • Impact of media advertising • Influence of vendor behavior • Role of brand trust |

• Regulate food marketing practices • Encourage responsible vendor labeling • Partner with trusted brands for public health messaging |

| Policy and Oversight | • Perceived negligence by health authorities • Concerns about misleading packaging |

• Enforce mandatory and transparent labeling standards • Monitor compliance through health ministries |

Discussion and Policy Implications

The findings underscored that participants' dietary decisions were predominantly shaped by the perceived healthiness of foods, taste preferences, media exposure and advertising, familial dietary patterns, and cost considerations. These results further corroborate existing evidence indicating that cognitive-emotional mechanisms—such as deeply-held health beliefs and formative personal experiences—serve as foundational drivers of food choice [20, 21]. Additionally, broader political and social structures, including national food regulations, food labeling standards, and media advertising policies, emerged as influential determinants of dietary behavior. This observation aligns with international studies conducted in countries such as China and Tanzania, which similarly highlight the critical role of socio-legislative dimensions in shaping dietary patterns [22-24].

While economic status was confirmed as a major barrier to the adoption of a healthy diet, the rising global prevalence of metabolic syndrome across both low- and high-income countries suggests that affordability alone does not account for dietary risk [24]. Participants also expressed concern over misleading food labels and insufficient regulatory oversight. These concerns are consistent with previous literature documenting the harmful effects of counterfeit food products and the misuse of pesticides, both of which undermine consumer trust and public health [22, 25]. Media exposure and brand trust were identified as significant influencers of food choice. Advertising—particularly on digital platforms—played a central role in shaping perceptions of product healthfulness. This finding is congruent with research from the United States, which demonstrates that social media, especially Facebook, substantially affects dietary decisions, with notable gender-based differences in perceived health risks [26]. Religious beliefs and cultural norms also intersected meaningfully with participants' dietary practices. This pattern is in line with studies from China, which have reported associations between culturally driven behaviors such as alcohol consumption and an elevated risk of metabolic disorders [27].

The findings underscored that participants' dietary decisions were predominantly shaped by the perceived healthiness of foods, taste preferences, media exposure and advertising, familial dietary patterns, and cost considerations. These results further corroborate existing evidence indicating that cognitive-emotional mechanisms—such as deeply-held health beliefs and formative personal experiences—serve as foundational drivers of food choice [20, 21]. Additionally, broader political and social structures, including national food regulations, food labeling standards, and media advertising policies, emerged as influential determinants of dietary behavior. This observation aligns with international studies conducted in countries such as China and Tanzania, which similarly highlight the critical role of socio-legislative dimensions in shaping dietary patterns [22-24].

While economic status was confirmed as a major barrier to the adoption of a healthy diet, the rising global prevalence of metabolic syndrome across both low- and high-income countries suggests that affordability alone does not account for dietary risk [24]. Participants also expressed concern over misleading food labels and insufficient regulatory oversight. These concerns are consistent with previous literature documenting the harmful effects of counterfeit food products and the misuse of pesticides, both of which undermine consumer trust and public health [22, 25]. Media exposure and brand trust were identified as significant influencers of food choice. Advertising—particularly on digital platforms—played a central role in shaping perceptions of product healthfulness. This finding is congruent with research from the United States, which demonstrates that social media, especially Facebook, substantially affects dietary decisions, with notable gender-based differences in perceived health risks [26]. Religious beliefs and cultural norms also intersected meaningfully with participants' dietary practices. This pattern is in line with studies from China, which have reported associations between culturally driven behaviors such as alcohol consumption and an elevated risk of metabolic disorders [27].

Table 3. Comprehensive of Themes and Participant Quotes on Nutritional Decision-Making in Individuals with Metabolic Syndrome

| Main Category | Theme Code & Number | Direct Participant Quote |

| Health and Nutrition Factors | 1. The usefulness of food products | • "It is important for me to have healthy food. For example, I eat a lot of beans and vegetables. I use red chicken and fish 1–2 times a week." (Female, 63) • "I buy most healthy food. I prefer their health to their taste." (Female, 64) • "I try not to buy things that are harmful to me when I go shopping." (Male, 40) |

| 2. Diseases can affect the diet | • "Before I got diabetes, only the taste of food mattered to me, but now I have to pay attention to the amount and type of sugar in my food." (Male, 21) • "Considering that I am overweight, I pay attention to the number of calories when buying products." (Male, 23) |

|

| 3. People's understanding of healthy food | • "Food that is not fried and has low fat is considered healthy." (Female, 63) • "Foods that do not have a lot of salt and fat, as well as vegetables and fruits, are healthy." (Female, 64) |

|

| 4. Healthy but harmful food | • "It may be healthy food, but some people cannot consume it due to their diseases." (Female, 63) • "Some foods used to be useful for me, but today I cannot eat them due to diabetes and high blood pressure." (Female, 62) |

|

| 5. Processed food products | • "Any food that is somehow out of its natural form is called processed food." (Female, 38) • "Some foods are modified and contain additives such as salt that are not good for health." (Female, 22) |

|

| Personal Preferences | 1. Prefer the taste and appearance of food products to its usefulness | • "The taste and deliciousness of the food products are important to me, and their healthiness is not important." (Female, 21) • "The foods consumed must be healthy, but two things are important to me: the descriptions on the packages and what I think about the appearance of the food." (Male, 61) |

| 2. Diet conflict between family members | • "I don't eat fast food at all, but my husband and son eat it." (Female, 62) | |

| Information & Label Use | 1. Food signs and tables | • "I know the two standard signs and the table of ingredients." (Female, 63) • "It works like a guide for those who have special diets or are suffering from a certain disease." (Female, 21) |

| 2. Paying attention to the guide of food products | • "These tables of ingredients assure us of the ingredients of a food and help a lot in choosing, especially for people with certain diseases." (Female, 63) • "I pay attention to the tables of food products and try to use those that have fewer calories." (Female, 21) |

|

| 3. Paying attention to the expiration date and standard signs on food packages | • "In addition to the list of ingredients, I also pay attention to the standard mark and the expiration date." (Female, 63) | |

| 4. The value of information on food packages | • "It is important to include information on the packages. It acts as a guide for people with special diseases or diets." (Female, 63) • "If all people pay attention to the tables of food products, they will not get sick and will stay healthy." (Female, 62) |

|

| 5. Uncertainty about the accuracy of nutrition label information | • "We need to be sure that the descriptions on the food packages are correct." (Male, 61) | |

| Label Literacy & Understanding | 1. The family's awareness of food labels, unlike the sick person | • "Even though I have high blood pressure, I did not pay attention to labels until now... But my wife knows these tables." (Male, 40) |

| 2. Correct understanding of food ingredient tables | • "Food tables can help us choose healthy foods if we know those ingredients. For example, if we do not know the normal blood sugar limit, it is useless to pay attention to these tables." (Male, 21) | |

| 3. Knowing a healthy diet | • "People should know themselves first and choose the desired food item based on that knowledge." (Male, 35) • "I look at the ingredient tables to see how much sugar is in the product, but it does not affect my choice." (Male, 35) |

|

| 4. Clear and attractive writing of nutrition labels | • "The writing should be large and attract attention." (Male, 62) • "Some people don't have enough information or literacy to read charts. It should be written clearly and concisely in Farsi that this food can increase your blood fat." (Female, 25) |

|

| Economic Constraints | 1. The effect of economic status on diet | • "Protein foods and dairy products are healthy, but they are used less because of the high cost." (Male, 62) • "When buying food products, I first look at my financial ability and then the price." (Female, 25) |

| 2. The compulsion to consume unhealthy food | • "When healthy foods are not available or their healthiness is uncertain, we may settle for higher-calorie, lower-quality foods." (Male, 61) | |

| External Influences | 1. The influence of the media on people's diet | • "Due to the many advertisements on radio and television and elsewhere, processed foods have become widespread, especially among young people and even children." (Male, 62) • "Healthy consumption can be promoted with more education via the media and more advertising about healthy products." (Female, 22) |

| 2. The attention of food companies to people's health | • "The existence of food tables on products shows that food companies care about people's health." (Male, 64) | |

| 3. People's awareness of healthy food products | • "Our high level of awareness can help us a lot in choosing healthy food products." (Male, 64) | |

| 4. The effect of food product sellers on people's health | • "Food vendors should be aware of the products they sell and classify them based on organic food or health labels and guide their customers." (Female, 62) | |

| 5. Attention to health in the future | • "Food is healthy if it does not cause health problems both in the short term and in the long term." (Female, 22) | |

| 6. Well-known and reliable food brands | • "If I want healthy food from outside, it must be a reputable brand." (Female, 23) | |

| Policy and Oversight | 1. Negligence of the Ministry of Health | • "If the Ministry of Health pays more attention to mandatory nutrition labels and their accuracy, it will benefit people's health." (Male, 62) |

| 2. Inserting false information about food to sell more | • "All necessary information must be real and correct, even if the goal is marketing." (Male, 61) |

Food labeling emerged as a particularly salient theme. Although participants expressed strong support for front-of-package (FOP) nutrition indicators, they simultaneously voiced concerns about the accuracy and trustworthiness of these labels. This duality mirrors findings from Brazil and South Korea, where clear, credible FOP labeling systems have been shown to positively influence consumer behavior and mitigate diet-related health risks [28-31].

Educational attainment also surfaced as a critical determinant of nutritional label utilization and subsequent food selection, with this relationship especially pronounced among female participants [29].

Although the present study did not explicitly examine regional foods such as seaweeds or tropical fruits, existing literature suggests that these foods may play a protective role against metabolic risk factors [32].

Policy Recommendations

1. Develop targeted nutrition education programs for individuals with metabolic syndrome [21, 30, 31].

Recommendation: Implement evidence-based educational campaigns and community workshops emphasizing label interpretation, metabolic syndrome awareness, and informed dietary choices.

Responsible Entities:

- Ministry of Health and Medical Education

- National Medical Association & Scientific Nutrition/Endocrinology Societies

- Primary Healthcare Centers and Community Health Networks

Recommendation: Mandate a unified, color-coded Front-of-Package Labeling (FoPL) system (e.g., traffic-light format) for all processed foods, supported by a robust auditing mechanism to verify health claims.

Responsible Entities:

- National Standardization Organization & Food and Drug Administration

- Provincial Departments of Standards

Recommendation: Provide targeted subsidies for essential healthy foods and expand farmers' markets or “healthy food zones” in underserved areas.

Responsible Entities:

- Ministry of Cooperatives, Labour, and Social Welfare

- Municipalities & Ministry of Agriculture

Recommendation: Restrict advertising of foods high in salt, sugar, and unhealthy fats during peak viewing hours and require digital influencers to include clear health warnings when promoting such products.

Responsible Entities:

- National Broadcasting Authority

- Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance & Digital Media Development Center

- Food and Drug Administration

Recommendation: Introduce a government-endorsed “Healthy Choice” certification seal and offer financial incentives for product reformulation to improve nutritional quality.

Responsible Entities:

- Food and Drug Administration & Ministry of Industry, Mine, and Trade

- Central Bank & Commercial Lending Banks

Recommendation: Establish a “National Committee for Healthy Nutrition” to coordinate cross-sector policies following a Health-in-All-Policies approach.

Responsible Entities:

- The Presidency (Vice-Presidency for Strategic Planning and Supervision)

- Ministries of Health, Education, Agriculture, Industry, and National Broadcasting Authority

Recommendation: Allocate research funding for clinical trials evaluating the effects of indigenous foods and integrate findings into culturally relevant dietary guidelines.

Responsible Entities:

• Vice-Presidency for Science and Technology & Ministry of Health

• Regional Universities of Medical Sciences & Research Institutes of Medicinal Plants

• Ministry of Agriculture

Transferability of Findings

The transferability of these findings should be interpreted with caution. Because the study sample was drawn from a limited geographical area, broader application of the results may be constrained.

Conclusion

The lived experiences of individuals with metabolic syndrome reveal a complex web of nutritional, economic, informational, and policy-related influences.

Addressing these factors requires coordinated action across education, regulation, and public engagement. Without informed and proactive policy measures, the burden of metabolic syndrome will continue to rise, undermining long-term health outcomes and straining healthcare systems [21-33].

Ethical Considerations

The Ethics Committee of Larestan University of Medical Sciences approved this study (IR.LARUMS.REC.1402.016), and participants provided written informed consent.

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to thank the Larestan University of Medical Sciences for their financial support of this research (Project No.1401-141). We also sincerely thank all the individuals who participated and cooperated in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

N/A

Authors' Contributions

Rafi Bezrafshan M.: contributed to the study design and supervision of the research process.

Masmouei B.: was responsible for drafting and writing the manuscript.

Mansouri A.: carried out the data analysis.

Barghi O.: conducted the interviews and participated in data analysis.

Modarresi M.J.: contributed to the editing and revision of the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final version of the paper.

Artificial Intelligence Utilization for Article Writing

The authors utilized artificial intelligence tools for assistance in grammar checking and language polishing during the manuscript preparation process. The conceptualization, data analysis, interpretation of results, and critical revision of the intellectual content remain solely the responsibility of the authors.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to privacy and ethical considerations, the raw interview transcripts are not publicly available.

Type of Study: Orginal research |

Subject:

Nursing

References

1. Castro-Barquero S, Ruiz-León AM, Sierra-Pérez M, Estruch R, Casas R. Dietary Strategies for Metabolic Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients. 2020 Oct;12(10):2983. [https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12102983] [PMID]

2. Law J, Martin E. Concise Medical Dictionary. 10th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2020. [https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780198836612.001.0001]

3. Nilsson PM, Tuomilehto J, Rydén L. The Metabolic Syndrome - What Is It and How Should It Be Managed? European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2019 Jun;26(2_suppl):33-46. [https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319886404] [PMID]

4. Paley CA, Johnson MI. Abdominal Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome: Exercise as Medicine? BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2018 Dec;10(1):7. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-018-0097-1] [PMID]

5. Kahn CR, Wang G, Lee KY. Altered Adipose Tissue and Adipocyte Function in the Pathogenesis of Metabolic Syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2019 Oct;129(10):3990-4000. [https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI129187] [PMID]

6. Ferns GA, Ghayour-Mobarhan M. Metabolic Syndrome in Iran: A Review. Translational Metabolic Syndrome Research. 2018 Dec;1:10-22. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmsr.2018.04.001]

7. Finicelli M, Squillaro T, Di Cristo F, Di Salle A, Melone MAB, Galderisi U, et al. Metabolic Syndrome, Mediterranean Diet, and Polyphenols: Evidence and Perspectives. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2019 May;234(5):5807-26. [https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.27506] [PMID]

8. Salas-Salvadó J, Guasch-Ferré M, Lee CH, Estruch R, Clish CB, Ros E. Protective Effects of the Mediterranean Diet on Type 2 Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome. The Journal of Nutrition. 2016 Apr;146(4):920S-927S. [https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.115.218487] [PMID]

9. Lackey DE, Lazaro RG, Li P, Johnson A, Hernandez-Carretero A, Weber N, et al. The Role of Dietary Fat in Obesity-Induced Insulin Resistance. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2016 Dec;311(6):E989-E997. [https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00323.2016] [PMID]

10. Wang T, Heianza Y, Sun D, Huang T, Ma W, Rimm EB, et al. Improving Adherence to Healthy Dietary Patterns, Genetic Risk, and Long Term Weight Gain: Gene-Diet Interaction Analysis in Two Prospective Cohort Studies. BMJ. 2018 Mar;360:j5644. [https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j5644] [PMID]

11. Grosso G, Galvano F. Mediterranean Diet Adherence in Children and Adolescents in Southern European Countries. NFS Journal. 2016 Mar;3:13-9. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nfs.2016.02.004]

12. Shangguan S, Afshin A, Shulkin M, Ma W, Marsden D, Smith J, et al. A Meta-Analysis of Food Labeling Effects on Consumer Diet Behaviors and Industry Practices. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2019 Feb;56(2):300-14. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.09.024] [PMID]

13. Gregori D, Ballali S, Vögele C, Galasso F, Widhalm K, Berchialla P, et al. What Is the Value Given by Consumers to Nutritional Label Information? Results from a Large Investigation in Europe. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2015;34(2):120-5. [https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2014.899936] [PMID]

14. Sánchez-García I, Rodríguez-Insuasti H, Martí-Parreño J, Sánchez-Mena A. Nutritional Traffic Light and Self-Regulatory Consumption: The Role of Emotions. British Food Journal. 2019 Jan;121(1):183-98. [https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-03-2018-0192]

15. Vears DF, Gillam L. Inductive Content Analysis: A Guide for Beginning Qualitative Researchers. Focus on Health Professional Education: A Multi-Professional Journal. 2022 Mar;23(1):111-27. [https://doi.org/10.11157/fohpe.v23i1.544]

16. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Circulation. 2002 Dec;106(25):3143-421. [https://doi.org/10.1161/circ.106.25.3143] [PMID]

17. Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, et al. Saturation in Qualitative Research: Exploring Its Conceptualization and Operationalization. Quality & Quantity. 2018 Jul;52(4):1893-907. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8] [PMID]

18. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative Content Analysis in Nursing Research: Concepts, Procedures and Measures to Achieve Trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004 Feb;24(2):105-12. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001] [PMID]

19. Enworo OC. Application of Guba and Lincoln's Parallel Criteria to Assess Trustworthiness of Qualitative Research on Indigenous Social Protection Systems. Qualitative Research Journal. 2023 Nov;23(4):372-84. [https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-08-2022-0116]

20. Chen PJ, Antonelli M. Conceptual Models of Food Choice: Influential Factors Related to Foods, Individual Differences, and Society. Foods. 2020 Dec;9(12):1898. [https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9121898] [PMID]

21. Leng G, Adan RA, Belot M, Brunstrom JM, De Graaf K, Dickson SL, et al. The Determinants of Food Choice. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2017 Aug;76(3):316-27. [https://doi.org/10.1017/S002966511600286X] [PMID]

22. Zikankuba VL, Mwanyika G, Ntwenya JE, James A. Pesticide Regulations and Their Malpractice Implications on Food and Environment Safety. Cogent Food & Agriculture. 2019 Jan;5(1):1601544. [https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1601544]

23. Saklayen MG. The Global Epidemic of the Metabolic Syndrome. Current Hypertension Reports. 2018 Feb;20(2):12. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-018-0812-z] [PMID]

24. Ma G. Food, Eating Behavior, and Culture in Chinese Society. Journal of Ethnic Foods. 2015 Dec;2(4):195-9. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jef.2015.11.004]

25. Handford CE, Campbell K, Elliott CT. Impacts of Milk Fraud on Food Safety and Nutrition with Special Emphasis on Developing Countries. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2016 Jan;15(1):130-42. [https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12181] [PMID]

26. Nelson AM, Fleming R. Gender Differences in Diet and Social Media: An Explorative Study. Appetite. 2019 Oct;142:104383. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.104383] [PMID]

27. Lin Y, Ying YY, Li SX, Wang SJ, Gong QH, Li H. Association between Alcohol Consumption and Metabolic Syndrome among Chinese Adults. Public Health Nutrition. 2021 Oct;24(14):4582-90. [https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020004449] [PMID]

28. Styne DM, Arslanian SA, Connor EL, Farooqi IS, Murad MH, Silverstein JH, et al. Pediatric Obesity-Assessment, Treatment, and Prevention: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2017 Mar;102(3):709-57. [https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-2573] [PMID]

29. Kim OY, Kwak SY, Kim B, Kim YS, Kim HY, Shin MJ. Selected Food Consumption Mediates the Association between Education Level and Metabolic Syndrome in Korean Adults. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism. 2017 May;70(2):122-31. [https://doi.org/10.1159/000470853] [PMID]

30. Egnell M, Crosetto P, d'Almeida T, Kesse-Guyot E, Touvier M, Ruffieux B, et al. Modelling the Impact of Different Front-of-Package Nutrition Labels on Mortality from Non-Communicable Chronic Disease. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2019 May;16(1):56. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0817-2] [PMID]

31. de Morais Sato P, Mais LA, Khandpur N, Ulian MD, Bortoletto Martins AP, Garcia MT, et al. Consumers' Opinions on Warning Labels on Food Packages: A Qualitative Study in Brazil. PLoS One. 2019 Jun;14(6):e0218813. [https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218813] [PMID]

32. John OD, du Preez R, Panchal SK, Brown L. Tropical Foods as Functional Foods for Metabolic Syndrome. Food & Function. 2020 Aug;11(8):6946-60. [https://doi.org/10.1039/D0FO01133A] [PMID]

33. Baudry J, Lelong H, Adriouch S, Julia C, Allès B, Hercberg S, et al. Association between Organic Food Consumption and Metabolic Syndrome: Cross-Sectional Results from the NutriNet-Santé Study. European Journal of Nutrition. 2018 Dec;57(7):2477-88. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-017-1520-1] [PMID]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |