Preventive Care in Nursing and Midwifery Journal

Volume 15, Issue 3 (7-2025)

Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J 2025, 15(3): 3-13 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.MUK.REC.1403.088

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Abdulhasan K A, Al-Doori N M, Valiee S. Predictors of hand hygiene adherence: A cross-sectional study of nurses in babylon, iraq. Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J 2025; 15 (3) :3-13

URL: http://nmcjournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-994-en.html

URL: http://nmcjournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-994-en.html

Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences , sinavaliee@yahoo.com

Full-Text [PDF 758 kb]

(153 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (519 Views)

Table 1. Demographic and Professional Characteristics of Participants (N = 150)

Table 2. Hand Hygiene Adherence and Method Selection Across Five Moments (N = 150)

Table 3. Factors Associated with Hand Hygiene Adherence Among Nurses (N = 150)

Table 4. Multiple Linear Regression Analysis Predicting Hand Hygiene Adherence (N = 150)

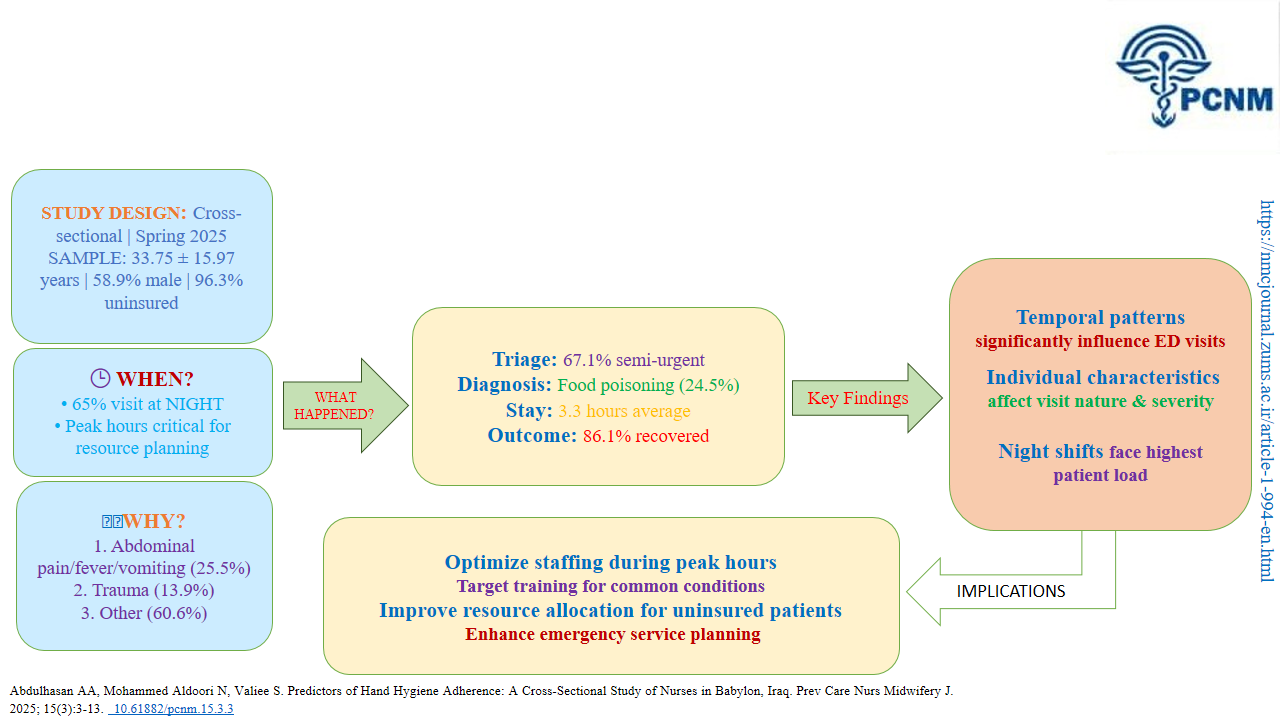

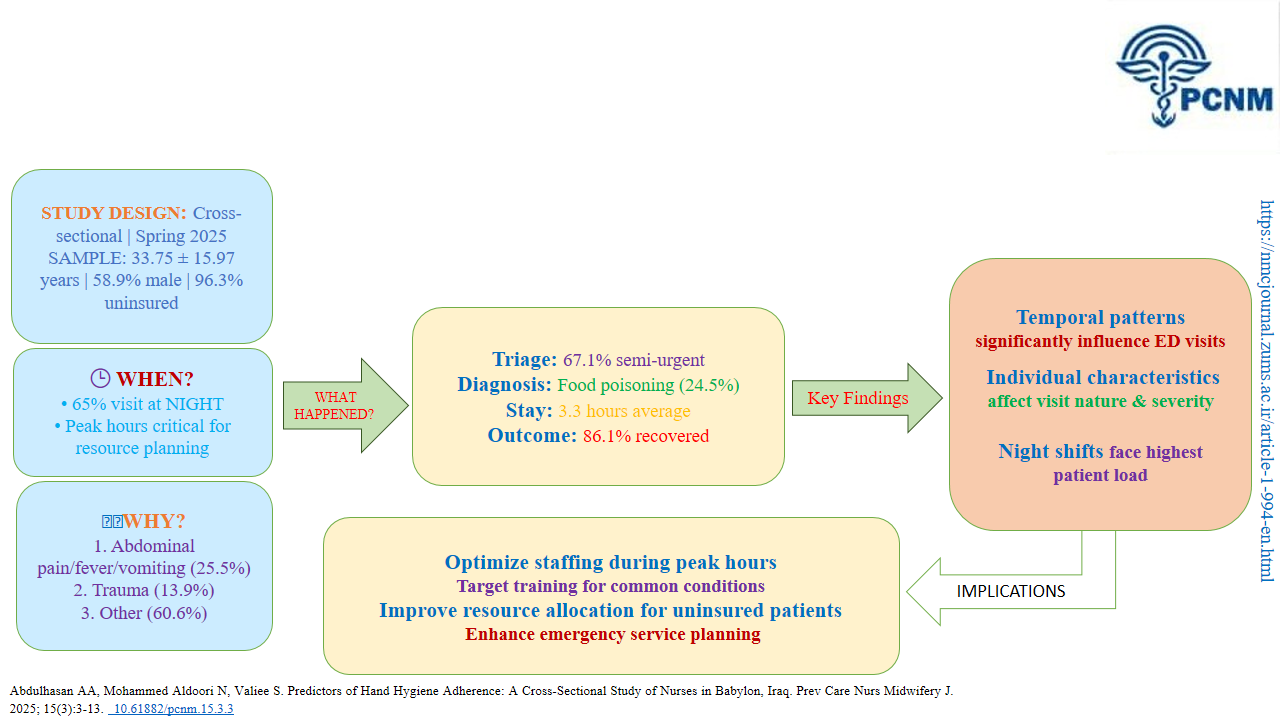

Knowledge Translation Statement

Audience: Nursing managers, infection prevention and control (IPC) officers, and hospital administrators

Individual factors like knowledge and attitude, alongside organizational factors such as workload and resource availability, are key predictors of hand hygiene adherence among nurses. To improve compliance, IPC programs must move beyond basic education to include regular audits with feedback, ensure consistent availability of alcohol-based hand rub at the point of care, and address systemic barriers like high workload to create a sustainable culture of safety.

Audience: Nursing managers, infection prevention and control (IPC) officers, and hospital administrators

Individual factors like knowledge and attitude, alongside organizational factors such as workload and resource availability, are key predictors of hand hygiene adherence among nurses. To improve compliance, IPC programs must move beyond basic education to include regular audits with feedback, ensure consistent availability of alcohol-based hand rub at the point of care, and address systemic barriers like high workload to create a sustainable culture of safety.

Full-Text: (21 Views)

Introduction

Hand hygiene is a vital practice at key moments and has been shown to reduce nosocomial infections. The term "nosocomial infections" refers to diseases patients acquire as a result of interaction with a healthcare facility or directly from medical treatment [1]. Nearly two million people worldwide are affected by nosocomial infections each year, with five to ten percent of them needing hospitalization [2]. In poor and middle-income countries, the rate of these infections is twice that of high-income countries [3]. The prevalence of nosocomial infections in sub-Saharan Africa has been reported to range from 1.6% to 28.7%, despite limited data on these infections in poor and middle-income countries, with rates of 13.4%, 11.4%, and 8% reported in Botswana, Malawi, and South Africa, respectively [4-6].

Patient, caregiver, and healthcare worker safety is severely threatened by nosocomial infections [7], with the highest rates in low- and middle-income countries being surgical site infections, urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and bloodstream infections [8]. A study at Baquba General Hospital in Iraq found that the most common types of these infections were urinary tract infections (40%), followed by surgical site infections (35.8%) and respiratory tract infections (23%) [9]. The worldwide compliance of healthcare workers to proper hand hygiene is typically below 50% (WHO), It is estimated that about fifty percent of nosocomial infections are transmitted by healthcare workers' hands [10, 11], which is very concerning and cannot be ignored. Handwashing with soap alone has been shown to reduce diarrhea cases by 30 to 47 percent, according to systematic review studies supporting the importance of hand cleaning in disease prevention [12, 13]. Therefore, healthcare workers are advised to wash their hands before patient contact, before performing aseptic procedures, after exposure to body fluids, after patient contact, and after touching the patient's environment, in line with the "My Five Moments for Hand Hygiene" guidelines recommended by the World Health Organization [14, 15]. However, adherence to hand hygiene protocols among healthcare workers remains low, with a global average reported at 38.7% [15]. In Iran, the average hand hygiene adherence among nurses has been reported as 40.5% [16]. Hand hygiene compliance is a major challenge in healthcare settings worldwide, including Iraq. Research has shown that hand hygiene compliance rates in healthcare environments are often below recommended levels, frequently falling below 40-50% in some countries, especially in resource-limited settings [17, 18]. An observational study of hand hygiene adherence among healthcare staff in the Kurdistan region of Iraq reported a rate of approximately 6.8% [19]. One study found that hand hygiene compliance in Iraqi hospitals was lower than international standards, with many hospitals showing rates below 50%. This was attributed to factors such as inadequate training, a lack of infrastructure, and a generally poor hygiene culture in healthcare facilities. Poor hand hygiene significantly contributes to the spread of healthcare-associated infections. In Iraq, as in many developing countries, the prevalence of nosocomial infections and infectious diseases, such as gastrointestinal infections, respiratory illnesses, and even bloodstream infections associated with healthcare, is high, worsened by insufficient adherence to hand hygiene guidelines [17, 18].

Although precise and current data on the exact prevalence and rates of hand hygiene adherence in Iraq are limited, existing studies suggest that compliance in healthcare settings remains suboptimal. The main challenges include inadequate infrastructure, lack of awareness, and insufficient training.

Nevertheless, global health initiatives and the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic have raised awareness and may have resulted in some improvements in recent years. Overall, understanding the level of adherence and its influencing factors is important, especially within Iraq's cultural context.

Objectives

This study aimed to assess hand hygiene adherence and its related factors among nurses in the hospitals of Babylon city, Iraq, in 2025.

Methods

Study Design

This study employed a cross-sectional design.

Participants and setting, the study population included all nurses working in Babylon, Iraq, in 2025. The data for this research were gathered from July 16, 2025, to August 30, 2025. Inclusion criteria were willingness to participate and holding at least an associate degree in nursing. Exclusion criteria were incomplete questionnaire responses.

The study was carried out in hospitals within the city of Babylon, Iraq. Babylon, also known as Al-Hillah, is a city in central Iraq. The research environment included several hospitals in the city, specifically: Al-Hillah Surgical Hospital, located in Al-Hillah, which offers surgical, laboratory, and forensic medical services; Babylon Hospital, specializing in pediatrics and obstetrics/gynecology, providing a broad range of healthcare services; and Marjan Teaching Hospital, also in Al-Hillah, part of the educational system, offering various medical services.

Sampling and Sample Size The study sample included 150 nurses working in various departments of hospitals in Babylon City, Iraq, who were selected through convenience sampling. Data collection involved using convenience sampling, and questionnaires were handed out in person to all nurses working in different general departments of the target hospitals.

The sample size was calculated using the formula and based on information from Moued et al. [19]. Since the reported adherence rate in the referenced study was 6.8%, and assuming a 95% confidence level (Z = 1.96) with a 5% margin of error (d = 0.05), the initial sample size was determined to be 97 nurses. Because data in the current study were collected through self-reporting-which can sometimes lead to over- or under-reporting of behaviors like hand hygiene-and to account for potential biases and an expected response rate of 80%, the sample size was increased to 122 participants. Finally, to achieve sufficient statistical power for detailed subgroup analyses and improve estimate accuracy, the final sample size was set at 150 participants.

Data Collection Tools Data were collected using three instruments: a demographic characteristics form, a Hand Hygiene Adherence Scale, and a questionnaire on factors associated with non-adherence to hand hygiene.

a) Demographic Characteristics: This included age, gender, education level, training, work experience, etc.

b) Hand Hygiene Adherence Scale: The WHO Hand Hygiene Technical Reference Manual was used to develop a self-report questionnaire for declarative hand hygiene adherence [20].

The questionnaire was customized and edited to assess adherence to hand hygiene protocols. The WHO's "My Five Moments for Hand Hygiene" outlines key moments when healthcare workers must perform hand hygiene to prevent the spread of infections. These moments are: 1. Before touching a patient, 2. Before clean/aseptic procedures, 3. After body fluid exposure/risk, 4. After touching a patient, and 5. After touching the patient's surroundings. The self-report scale asked nurses to rate their adherence to these five moments on a Likert scale from 1 to 5, where 1 represented "Never" and 5 represented "Always". Subsequently, they were asked to specify which method of hand hygiene they used in each situation (handwashing with soap and water, use of alcohol-based hand rub, both, or neither).

c) Questionnaire on Factors Associated with Non-Adherence to Hand Hygiene: This questionnaire asked nurses to indicate their level of agreement with a list of 26 factors on a Likert scale from 1 ("Strongly Disagree") to 5 ("Strongly Agree"). The factors pertained to personal, organizational, psychosocial, and environmental elements previously linked to nurses' hand hygiene adherence in previous studies [17-26].

For qualitative content validity, the questionnaires were reviewed by 10 faculty members of the Nursing and Midwifery School, and after incorporating their feedback, the tools were translated into Arabic for use. The original questionnaires were independently translated into Arabic by two bilingual translators. To create a single, conceptually accurate version, a panel then synthesized these two translations, resolving any discrepancies. Reliability was assessed by calculating Cronbach's alpha after the questionnaires were piloted with 30 nurses not participating in the main study, resulting in a value of 0.827. After data collection and analysis, the level of hand hygiene adherence among nurses, the methods of adherence, and the factors associated with adherence were reported.

Procedure

Data collection took place between July 16, 2025, and August 30, 2025. Following official permissions from the relevant hospital administrations in Babylon city, the researcher visited the participating hospital wards during shift changes. Nurses who were present and met the inclusion criteria were invited to participate using a convenience sampling method. The researcher introduced the study, explained its purpose, and outlined the procedures to all eligible nurses. Those who agreed to participate provided informed consent. The questionnaire package was then distributed. Participants completed the questionnaires in a quiet corner or a private room on the ward, returning them to the researcher immediately upon completion. The average time taken to complete the questionnaires was approximately 10 minutes.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS v.23. Frequency distribution tables were generated for qualitative variables, and measures of central tendency and dispersion with a 95% confidence interval were calculated for quantitative variables. The Shapiro-Wilk test results did not confirm the normal distribution assumption for the total score and its dimensions; therefore, non-parametric tests were used for analysis. The Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis test, and Spearman's correlation coefficient were employed to examine the study hypotheses. Furthermore, multivariable analysis was performed using logistic regression to identify the independent factors associated with hand hygiene adherence. A significance level of 5% was considered for all tests.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The study included nurses with a mean age of 27.91 years (SD = 4.4) and a mean work experience of 5.05 years (SD = 4.04). The majority of participants were female (82.7%), held a bachelor's degree (51.3%), and had attended hand hygiene training courses (59.3%). Most nurses (51.3%) were rated as having a moderate level of infection control knowledge (Table 1).

Hand Hygiene Adherence Patterns and Methods

Nurses' hand hygiene adherence varied significantly across different clinical situations. Adherence was highest after exposure to body fluids (90.7% always adhered) and after patient contact (86.7% always adhered). In contrast, adherence was lowest before patient contact, with only 66.7% always adhering. The most frequently reported method across all situations was handwashing with soap and water, with its highest use before patient contact (54.7%). A combined use of handwashing and alcohol-based hand rub was also common (up to 28% before patient contact), while a small percentage (0.7% to 4%) reported using no method in various situations (Table 2).

Key Barriers to Adherence

The most significant barriers to hand hygiene compliance were related to workload and skin integrity. Nearly half of the nurses (46.7%) strongly agreed that high workload was a hindering factor. Skin issues were also prominent, with 32.0% strongly agreeing that skin dryness, cracking, or itching, and 30.0% strongly agreeing that skin damage from alcohol-based solutions impeded adherence. In contrast, intrinsic motivational factors, such as protecting oneself (0.7%) or one's patients (3.3%) from infection, received the lowest levels of strong agreement as barriers (Table 3).

Predictors of Adherence: Regression Analysis

A multiple logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify predictors of hand hygiene adherence. Gender was the only variable that emerged as a statistically significant predictor. The analysis yielded an unstandardized coefficient (B) of -1.323, indicating that the adherence score for male nurses was, on average, 1.323 units lower than that of female nurses (p < 0.05) (Table 4).

Hand hygiene is a vital practice at key moments and has been shown to reduce nosocomial infections. The term "nosocomial infections" refers to diseases patients acquire as a result of interaction with a healthcare facility or directly from medical treatment [1]. Nearly two million people worldwide are affected by nosocomial infections each year, with five to ten percent of them needing hospitalization [2]. In poor and middle-income countries, the rate of these infections is twice that of high-income countries [3]. The prevalence of nosocomial infections in sub-Saharan Africa has been reported to range from 1.6% to 28.7%, despite limited data on these infections in poor and middle-income countries, with rates of 13.4%, 11.4%, and 8% reported in Botswana, Malawi, and South Africa, respectively [4-6].

Patient, caregiver, and healthcare worker safety is severely threatened by nosocomial infections [7], with the highest rates in low- and middle-income countries being surgical site infections, urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and bloodstream infections [8]. A study at Baquba General Hospital in Iraq found that the most common types of these infections were urinary tract infections (40%), followed by surgical site infections (35.8%) and respiratory tract infections (23%) [9]. The worldwide compliance of healthcare workers to proper hand hygiene is typically below 50% (WHO), It is estimated that about fifty percent of nosocomial infections are transmitted by healthcare workers' hands [10, 11], which is very concerning and cannot be ignored. Handwashing with soap alone has been shown to reduce diarrhea cases by 30 to 47 percent, according to systematic review studies supporting the importance of hand cleaning in disease prevention [12, 13]. Therefore, healthcare workers are advised to wash their hands before patient contact, before performing aseptic procedures, after exposure to body fluids, after patient contact, and after touching the patient's environment, in line with the "My Five Moments for Hand Hygiene" guidelines recommended by the World Health Organization [14, 15]. However, adherence to hand hygiene protocols among healthcare workers remains low, with a global average reported at 38.7% [15]. In Iran, the average hand hygiene adherence among nurses has been reported as 40.5% [16]. Hand hygiene compliance is a major challenge in healthcare settings worldwide, including Iraq. Research has shown that hand hygiene compliance rates in healthcare environments are often below recommended levels, frequently falling below 40-50% in some countries, especially in resource-limited settings [17, 18]. An observational study of hand hygiene adherence among healthcare staff in the Kurdistan region of Iraq reported a rate of approximately 6.8% [19]. One study found that hand hygiene compliance in Iraqi hospitals was lower than international standards, with many hospitals showing rates below 50%. This was attributed to factors such as inadequate training, a lack of infrastructure, and a generally poor hygiene culture in healthcare facilities. Poor hand hygiene significantly contributes to the spread of healthcare-associated infections. In Iraq, as in many developing countries, the prevalence of nosocomial infections and infectious diseases, such as gastrointestinal infections, respiratory illnesses, and even bloodstream infections associated with healthcare, is high, worsened by insufficient adherence to hand hygiene guidelines [17, 18].

Although precise and current data on the exact prevalence and rates of hand hygiene adherence in Iraq are limited, existing studies suggest that compliance in healthcare settings remains suboptimal. The main challenges include inadequate infrastructure, lack of awareness, and insufficient training.

Nevertheless, global health initiatives and the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic have raised awareness and may have resulted in some improvements in recent years. Overall, understanding the level of adherence and its influencing factors is important, especially within Iraq's cultural context.

Objectives

This study aimed to assess hand hygiene adherence and its related factors among nurses in the hospitals of Babylon city, Iraq, in 2025.

Methods

Study Design

This study employed a cross-sectional design.

Participants and setting, the study population included all nurses working in Babylon, Iraq, in 2025. The data for this research were gathered from July 16, 2025, to August 30, 2025. Inclusion criteria were willingness to participate and holding at least an associate degree in nursing. Exclusion criteria were incomplete questionnaire responses.

The study was carried out in hospitals within the city of Babylon, Iraq. Babylon, also known as Al-Hillah, is a city in central Iraq. The research environment included several hospitals in the city, specifically: Al-Hillah Surgical Hospital, located in Al-Hillah, which offers surgical, laboratory, and forensic medical services; Babylon Hospital, specializing in pediatrics and obstetrics/gynecology, providing a broad range of healthcare services; and Marjan Teaching Hospital, also in Al-Hillah, part of the educational system, offering various medical services.

Sampling and Sample Size The study sample included 150 nurses working in various departments of hospitals in Babylon City, Iraq, who were selected through convenience sampling. Data collection involved using convenience sampling, and questionnaires were handed out in person to all nurses working in different general departments of the target hospitals.

The sample size was calculated using the formula and based on information from Moued et al. [19]. Since the reported adherence rate in the referenced study was 6.8%, and assuming a 95% confidence level (Z = 1.96) with a 5% margin of error (d = 0.05), the initial sample size was determined to be 97 nurses. Because data in the current study were collected through self-reporting-which can sometimes lead to over- or under-reporting of behaviors like hand hygiene-and to account for potential biases and an expected response rate of 80%, the sample size was increased to 122 participants. Finally, to achieve sufficient statistical power for detailed subgroup analyses and improve estimate accuracy, the final sample size was set at 150 participants.

Data Collection Tools Data were collected using three instruments: a demographic characteristics form, a Hand Hygiene Adherence Scale, and a questionnaire on factors associated with non-adherence to hand hygiene.

a) Demographic Characteristics: This included age, gender, education level, training, work experience, etc.

b) Hand Hygiene Adherence Scale: The WHO Hand Hygiene Technical Reference Manual was used to develop a self-report questionnaire for declarative hand hygiene adherence [20].

The questionnaire was customized and edited to assess adherence to hand hygiene protocols. The WHO's "My Five Moments for Hand Hygiene" outlines key moments when healthcare workers must perform hand hygiene to prevent the spread of infections. These moments are: 1. Before touching a patient, 2. Before clean/aseptic procedures, 3. After body fluid exposure/risk, 4. After touching a patient, and 5. After touching the patient's surroundings. The self-report scale asked nurses to rate their adherence to these five moments on a Likert scale from 1 to 5, where 1 represented "Never" and 5 represented "Always". Subsequently, they were asked to specify which method of hand hygiene they used in each situation (handwashing with soap and water, use of alcohol-based hand rub, both, or neither).

c) Questionnaire on Factors Associated with Non-Adherence to Hand Hygiene: This questionnaire asked nurses to indicate their level of agreement with a list of 26 factors on a Likert scale from 1 ("Strongly Disagree") to 5 ("Strongly Agree"). The factors pertained to personal, organizational, psychosocial, and environmental elements previously linked to nurses' hand hygiene adherence in previous studies [17-26].

For qualitative content validity, the questionnaires were reviewed by 10 faculty members of the Nursing and Midwifery School, and after incorporating their feedback, the tools were translated into Arabic for use. The original questionnaires were independently translated into Arabic by two bilingual translators. To create a single, conceptually accurate version, a panel then synthesized these two translations, resolving any discrepancies. Reliability was assessed by calculating Cronbach's alpha after the questionnaires were piloted with 30 nurses not participating in the main study, resulting in a value of 0.827. After data collection and analysis, the level of hand hygiene adherence among nurses, the methods of adherence, and the factors associated with adherence were reported.

Procedure

Data collection took place between July 16, 2025, and August 30, 2025. Following official permissions from the relevant hospital administrations in Babylon city, the researcher visited the participating hospital wards during shift changes. Nurses who were present and met the inclusion criteria were invited to participate using a convenience sampling method. The researcher introduced the study, explained its purpose, and outlined the procedures to all eligible nurses. Those who agreed to participate provided informed consent. The questionnaire package was then distributed. Participants completed the questionnaires in a quiet corner or a private room on the ward, returning them to the researcher immediately upon completion. The average time taken to complete the questionnaires was approximately 10 minutes.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS v.23. Frequency distribution tables were generated for qualitative variables, and measures of central tendency and dispersion with a 95% confidence interval were calculated for quantitative variables. The Shapiro-Wilk test results did not confirm the normal distribution assumption for the total score and its dimensions; therefore, non-parametric tests were used for analysis. The Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis test, and Spearman's correlation coefficient were employed to examine the study hypotheses. Furthermore, multivariable analysis was performed using logistic regression to identify the independent factors associated with hand hygiene adherence. A significance level of 5% was considered for all tests.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The study included nurses with a mean age of 27.91 years (SD = 4.4) and a mean work experience of 5.05 years (SD = 4.04). The majority of participants were female (82.7%), held a bachelor's degree (51.3%), and had attended hand hygiene training courses (59.3%). Most nurses (51.3%) were rated as having a moderate level of infection control knowledge (Table 1).

Hand Hygiene Adherence Patterns and Methods

Nurses' hand hygiene adherence varied significantly across different clinical situations. Adherence was highest after exposure to body fluids (90.7% always adhered) and after patient contact (86.7% always adhered). In contrast, adherence was lowest before patient contact, with only 66.7% always adhering. The most frequently reported method across all situations was handwashing with soap and water, with its highest use before patient contact (54.7%). A combined use of handwashing and alcohol-based hand rub was also common (up to 28% before patient contact), while a small percentage (0.7% to 4%) reported using no method in various situations (Table 2).

Key Barriers to Adherence

The most significant barriers to hand hygiene compliance were related to workload and skin integrity. Nearly half of the nurses (46.7%) strongly agreed that high workload was a hindering factor. Skin issues were also prominent, with 32.0% strongly agreeing that skin dryness, cracking, or itching, and 30.0% strongly agreeing that skin damage from alcohol-based solutions impeded adherence. In contrast, intrinsic motivational factors, such as protecting oneself (0.7%) or one's patients (3.3%) from infection, received the lowest levels of strong agreement as barriers (Table 3).

Predictors of Adherence: Regression Analysis

A multiple logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify predictors of hand hygiene adherence. Gender was the only variable that emerged as a statistically significant predictor. The analysis yielded an unstandardized coefficient (B) of -1.323, indicating that the adherence score for male nurses was, on average, 1.323 units lower than that of female nurses (p < 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 1. Demographic and Professional Characteristics of Participants (N = 150)

| Variable | Category/Level | n | % |

| Age (years) | |||

| M (SD) | 27.91 (4.40) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 124 | 82.7 | |

| Male | 26 | 17.3 | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 80 | 53.3 | |

| Single | 70 | 46.7 | |

| Education Level | |||

| Diploma | 60 | 40.0 | |

| Associate Degree | 8 | 5.3 | |

| Bachelor's Degree | 77 | 51.3 | |

| Master's Degree | 5 | 3.3 | |

| Employment Status | |||

| Permanent | 148 | 98.7 | |

| Contractual | 2 | 1.3 | |

| Work Shift | |||

| Fixed | 115 | 76.7 | |

| Rotating | 35 | 23.3 | |

| Work Experience (years) | |||

| M (SD) | 5.05 (4.04) | ||

| Hospital of Service | |||

| Hila Teaching Hospital | 50 | 33.3 | |

| Babol Teaching Hospital | 50 | 33.3 | |

| Imam Sadeq Teaching Hospital | 50 | 33.3 | |

| History of Attending Infection Control Training Courses | |||

| Yes | 80 | 53.3 | |

| No | 70 | 46.7 | |

| History of Attending Hand Hygiene Training Courses | |||

| Yes | 89 | 59.3 | |

| No | 61 | 40.7 | |

| Awareness Level of Infection Control Methods | |||

| Poor | 19 | 12.7 | |

| Moderate | 77 | 51.3 | |

| Good | 54 | 36.0 | |

| Perceived Economic Status | |||

| Poor | 7 | 4.7 | |

| Moderate | 101 | 67.3 | |

| Good | 42 | 28.0 |

Table 2. Hand Hygiene Adherence and Method Selection Across Five Moments (N = 150)

| Adherence Level | Method | ||||||||

| Moment of Hand Hygiene | Always n (%) |

Often n (%) |

Sometimes n (%) |

Rarely n (%) |

Never n (%) |

Hand Washing n (%) |

Hand Rub n (%) |

Both n (%) |

None n (%) |

| Before touching a patient | 100 (66.7) | 26 (17.3) | 17 (11.3) | 5 (3.3) | 2 (1.3) | 82 (54.7) | 20 (13.3) | 42 (28.0) | 6 (4.0) |

| Before performing an aseptic procedure | 119 (79.3) | 20 (13.3) | 8 (5.3) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.3) | 69 (46.0) | 20 (13.3) | 56 (37.3) | 5 (3.3) |

| After exposure to body fluids | 136 (90.7) | 9 (6.0) | 4 (2.7) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 70 (46.7) | 13 (8.7) | 65 (43.3) | 2 (1.3) |

| After touching a patient | 130 (86.7) | 12 (8.0) | 8 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 65 (43.3) | 19 (12.7) | 64 (42.7) | 2 (1.3) |

| After touching the patient's surroundings | 119 (79.3) | 19 (12.7) | 10 (6.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 64 (42.7) | 21 (14.0) | 64 (42.7) | 1 (0.7) |

Table 3. Factors Associated with Hand Hygiene Adherence Among Nurses (N = 150)

| Factor | Strongly Agree n (%) |

Agree n (%) |

Neutral n (%) |

Disagree n (%) |

Strongly Disagree n (%) |

| High workload | 70 (46.7) | 44 (29.3) | 23 (15.3) | 10 (6.7) | 3 (2.0) |

| Forgetfulness | 33 (22.0) | 45 (30.0) | 36 (24.0) | 31 (20.7) | 5 (3.3) |

| Lack of time | 40 (26.7) | 40 (26.7) | 36 (24.0) | 27 (18.0) | 7 (4.7) |

| Uncertainty about when hand hygiene is necessary | 31 (20.7) | 36 (24.0) | 24 (16.0) | 32 (21.3) | 27 (18.0) |

| Unavailability of hand rub or sink | 34 (22.7) | 34 (22.7) | 40 (26.7) | 32 (21.3) | 10 (6.7) |

| Soap damages my skin | 41 (27.3) | 34 (22.7) | 26 (17.3) | 30 (20.0) | 19 (12.7) |

| Alcohol-based hand rub damages my skin | 45 (30.0) | 42 (28.0) | 22 (14.7) | 27 (18.0) | 14 (9.3) |

| I have dry, cracked, or itchy skin on my hands | 48 (32.0) | 46 (30.7) | 19 (12.7) | 27 (18.0) | 10 (6.7) |

| Hospital environment supports good hand hygiene practices | 26 (17.3) | 44 (29.3) | 75 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (3.3) |

| Ongoing training on hand hygiene is available | 29 (19.3) | 34 (22.7) | 81 (54.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (4.0) |

| Presence of reminders and posters in the ward | 27 (18.0) | 44 (29.3) | 74 (49.3) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (3.3) |

| Presence of electronic reminder systems in the ward | 28 (18.7) | 42 (28.0) | 73 (48.7) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (4.7) |

| Receiving appropriate feedback and encouragement from the system | 31 (20.7) | 50 (33.3) | 65 (43.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.7) |

| Management enforcement of hand hygiene policies and guidelines | 24 (16.0) | 47 (31.3) | 72 (48.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (4.7) |

| Receiving system feedback/encouragement for compliance | 33 (22.0) | 46 (30.7) | 68 (45.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.0) |

| Belief in the necessity of hand hygiene to prevent infection | 7 (4.7) | 29 (19.3) | 114 (76.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Confidence in my knowledge of hand hygiene techniques | 12 (8.0) | 45 (30.0) | 91 (60.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.3) |

| Workload affects my ability to consistently perform hand hygiene | 37 (24.7) | 34 (22.7) | 77 (51.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.3) |

| Motivation to follow hand hygiene guidelines | 13 (8.7) | 52 (34.7) | 84 (56.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| Sense of responsibility | 36 (24.0) | 38 (25.3) | 73 (48.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.0) |

| Protecting my patients | 5 (3.3) | 19 (12.7) | 125 (83.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| Protecting myself from infection | 1 (0.7) | 24 (16.0) | 124 (82.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| Protecting both the patient and myself | 5 (3.3) | 18 (12.0) | 126 (84.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| Fear of reprimand for non-compliance | 20 (13.3) | 33 (22.0) | 80 (53.3) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (11.3) |

| Non-compliance with hand hygiene by colleagues | 30 (20.0) | 30 (20.0) | 76 (50.7) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (9.3) |

| Hand hygiene culture among colleagues | 13 (8.7) | 48 (32.0) | 85 (56.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.7) |

Table 4. Multiple Linear Regression Analysis Predicting Hand Hygiene Adherence (N = 150)

| Variable | B | SE | β | t | p |

| Constant | 25.014 | 2.624 | 9.531 | 0.001 | |

| Age | 0.049 | 0.055 | 0.098 | 0.897 | 0.372 |

| Gender (Male) | -1.323 | 0.546 | -0.227 | -2.422 | 0.017 |

| Marital Status (Married) | 0.022 | 0.411 | 0.005 | 0.054 | 0.957 |

| Work Experience (years) | 0.077 | 0.062 | 0.142 | 1.258 | 0.211 |

| Work Shift (Rotating) | -0.016 | 0.457 | -0.003 | -0.035 | 0.972 |

| Education Level | -0.182 | 0.188 | -0.083 | -0.968 | 0.335 |

| Economic Status | -0.373 | 0.375 | -0.088 | -0.994 | 0.322 |

| Infection Control Knowledge | 0.403 | 0.295 | 0.120 | 1.369 | 0.173 |

| Hand Hygiene Training | -0.379 | 0.415 | -0.085 | -0.913 | 0.363 |

| Infection Control Training | 0.073 | 0.422 | 0.017 | 0.173 | 0.863 |

| Employment Status | -1.537 | 1.590 | -0.080 | -0.967 | 0.335 |

| Work Department | 0.289 | 0.234 | 0.107 | 1.232 | 0.220 |

Discussion

The study revealed a clear pattern of hand hygiene compliance among nurses, characterized by higher self-reported adherence in situations perceived as personally protective (e.g., after exposure to body fluids) compared to those primarily protective for the patient (e.g., before patient contact). The most significant barriers were high workload and skin problems, and gender emerged as a key predictor of adherence.

The study showed a distinct pattern of hand hygiene compliance among nurses, with the highest rates seen after potential contamination-90.7% following exposure to body fluids and 86.7% after patient contact. In contrast, compliance was much lower in preventive situations, such as before patient contact, where only 66.7% reported consistent adherence. This indicates that adherence is strongly affected by the perceived personal risk of contamination rather than the protective measures for patients.

This variability in situations aligns with international research, including studies from Norway [24]. Although the self-reported adherence rates in this study seem relatively high, they sharply differ from observational studies in other parts of Iraq, like Kurdistan, where adherence was as low as 6.8% [19]. This difference probably reflects the limitations of self-reporting, a method known to overestimate actual behavior, as shown in a Kuwaiti study [27].

The consistently lower compliance in preventive situations underscores the impact of contextual barriers. The most significant obstacles were high workload, reported by 46.7% of nurses as a major barrier, and skin issues, including dryness and damage from agents, strongly agreed upon by 32.0% and 30.0% of nurses, respectively. These include high workload, time constraints, and skin problems caused by cleaning agents; factors also identified in studies from Ethiopia [26] and other parts of Iraq [28]. Consequently, despite seemingly better adherence in Babylon, the findings highlight an urgent need for targeted interventions. These should focus on improving preventive practices through education, providing skin-friendly antiseptics, and fostering a stronger culture of patient safety.

Hand washing with soap and water was the main method used by 54.7% of nurses before patient contact and 42.7% after touching the patient's environment. Although the combined use of both handwashing and alcohol-based hand rub was fairly common (peaking at 28%), a concerning 0.7-4% of nurses used neither method in various situations.

This preference for traditional handwashing aligns with findings from Iraqi ICU studies [18], likely reflecting ingrained habits and the availability of sinks. However, it contradicts international guidelines that recommend alcohol-based hand rub as the preferred method due to its superior efficacy and skin tolerance [27]. The low utilization of hand rub suggests barriers such as inadequate access, insufficient training, or persistent misconceptions. Although some nurses demonstrated good practice by using both methods, the consistent non-adherence by a small group echoes concerning findings from observational studies in Kurdistan [19], highlighting ongoing behavioral challenges likely driven by high workload and skin problems.

The pattern observed in this study shows that while nurses generally follow hand hygiene guidelines, the quality and effectiveness of their methods need significant improvement. Promoting alcohol-based hand rub as the preferred method is crucial. This can be achieved through ongoing education to correct misconceptions, ensuring hand rub is always available at all points of care, and providing skin-care products to reduce side effects. This comprehensive approach is essential for improving infection control in Iraqi hospitals.

The pattern observed in this study shows that while nurses generally follow hand hygiene guidelines, the quality and effectiveness of their methods need significant improvement. Promoting alcohol-based hand rub as the preferred method is crucial. This can be achieved through ongoing education to correct misconceptions, ensuring hand rub is always available at all points of care, and providing skin-care products to reduce side effects. This comprehensive approach is essential for improving infection control in Iraqi hospitals.

The study identified a critical triad of failure in hand hygiene adherence, driven by systemic barriers rather than individual negligence. The primary obstacles were high workload (76%) and lack of time (53.4%), confirming work pressure as a universal challenge [20-26]. Furthermore, a significant occupational health crisis was revealed, with over half of nurses reporting skin problems from both soap (50%) and antiseptic solutions (58%), and 62.7% suffering from dryness or cracking. This explains the preference for traditional handwashing and highlights harmful products as a major physical barrier [27]. These findings demonstrate that theoretical training alone is insufficient [29]. A successful intervention requires a fundamental, multi-dimensional approach addressing three core areas simultaneously: Human Resources to reduce workload through adequate staffing; Logistics to provide skin-compatible antiseptics and moisturizers; and Organizational Culture to foster strong leadership and a supportive, blame-free environment. Ultimately, resolving this crisis depends on recognizing it as a systemic failure, requiring committed resource allocation and managerial action to create a sustainable solution.

Among all demographic and professional variables examined, gender was the only significant predictor of hand hygiene compliance, with male nurses showing notably lower adherence scores than females. However, it is important to interpret this finding with caution. The small number of male participants in our sample (17.3%) limits the generalizability and stability of this result. This finding aligns with regional studies in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait [21, 27], indicating that deeply rooted sociocultural and attitudinal factors may contribute to this ongoing gender disparity in compliance. Conversely, the absence of significance for other characteristics, such as age and education, agrees with research from Malawi [23], emphasizing that organizational and environmental barriers, like high workload and skin problems, have a much stronger impact on hand hygiene behavior than most personal traits. This pattern suggests that in resource-limited settings, systemic issues affect all staff equally, with gender being one of the few individual factors that continue to influence behavior despite these overwhelming contextual challenges.

The findings offer critical insights for strengthening preventive care. First, interventions must move beyond basic education to address the systemic barriers of workload and skin health. This includes advocating for adequate staffing and providing skin-friendly hand rubs and moisturizers. Second, promoting alcohol-based hand rubs as the gold standard is essential for improving practice quality. Finally, fostering a supportive organizational culture with strong leadership is crucial. For midwifery practice, these measures are vital to protect both healthcare workers and vulnerable patients, particularly mothers and newborns, from preventable infections.

This study has several limitations: the use of convenience sampling, which may limit the generalizability of the findings, and the cultural differences, which could have influenced nurses' understanding and responses to the questionnaires. Additionally, non-cooperation from some nurses due to workload or time constraints might have decreased the sample size and impacted data quality. Moreover, using self-report questionnaires may have introduced social desirability bias, as participants might not have reported information accurately out of concern about being judged. To address these limitations, efforts were made to minimize cultural impact by accurately translating the questionnaires into Arabic and consulting with a local advisor in Iraq. Increased cooperation was encouraged by motivating nurses and explaining the importance of the research. To reduce social desirability bias, anonymous data collection methods were used.

Conclusions

This study presents a complex view of hand hygiene adherence among nurses in Babylon, Iraq, characterized by situation-dependent compliance. Compliance was highest after risky exposures like contact with body fluids, but lowest in preventive moments such as before patient contact—showing nurses often prioritize self-protection over patient safety. The main barriers were systemic, including high workload and skin issues caused by antiseptics. Gender was a significant independent predictor, with male nurses consistently showing lower adherence. This is worsened by the common use of less effective handwashing with soap instead of preferred alcohol-based rubs.

Improving adherence requires a comprehensive approach that addresses organizational barriers such as workload, ensures the provision of skin-friendly products, conducts targeted training especially for male nurses, and promotes a strong culture of safety for both patients and staff.

Success depends on committed leadership to foster an environment where hand hygiene becomes an unavoidable standard.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in strict accordance with ethical principles, which involved obtaining formal ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUK.REC.1404.137) and securing the necessary permissions from relevant university and hospital administrations. The purpose and procedures of the research were thoroughly explained to all participating head nurses and nurses, from whom informed consent was obtained. The confidentiality of all collected data was guaranteed, participation was entirely voluntary, and a summary of the findings was made available to both participants and relevant officials upon request.

Acknowledgments

This study was derived from the first author's Master of Science in Medical-Surgical Nursing thesis. The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the nurses who participated in this study, as well as to the administrators of the teaching hospitals in Babylon city for their cooperation and support in facilitating data collection. We also extend our thanks to the International Affairs Office of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences for their assistance.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' Contributions

Abdulabbas Abdulhasan K: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft Preparation.

Mohammed Aldoori N: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – Review & Editing.

Valiee S: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing – Review & Editing.

All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Artificial Intelligence Utilization for Article Writing

We used artificial intelligence chatbots to improve the readability and language of the work.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The study revealed a clear pattern of hand hygiene compliance among nurses, characterized by higher self-reported adherence in situations perceived as personally protective (e.g., after exposure to body fluids) compared to those primarily protective for the patient (e.g., before patient contact). The most significant barriers were high workload and skin problems, and gender emerged as a key predictor of adherence.

The study showed a distinct pattern of hand hygiene compliance among nurses, with the highest rates seen after potential contamination-90.7% following exposure to body fluids and 86.7% after patient contact. In contrast, compliance was much lower in preventive situations, such as before patient contact, where only 66.7% reported consistent adherence. This indicates that adherence is strongly affected by the perceived personal risk of contamination rather than the protective measures for patients.

This variability in situations aligns with international research, including studies from Norway [24]. Although the self-reported adherence rates in this study seem relatively high, they sharply differ from observational studies in other parts of Iraq, like Kurdistan, where adherence was as low as 6.8% [19]. This difference probably reflects the limitations of self-reporting, a method known to overestimate actual behavior, as shown in a Kuwaiti study [27].

The consistently lower compliance in preventive situations underscores the impact of contextual barriers. The most significant obstacles were high workload, reported by 46.7% of nurses as a major barrier, and skin issues, including dryness and damage from agents, strongly agreed upon by 32.0% and 30.0% of nurses, respectively. These include high workload, time constraints, and skin problems caused by cleaning agents; factors also identified in studies from Ethiopia [26] and other parts of Iraq [28]. Consequently, despite seemingly better adherence in Babylon, the findings highlight an urgent need for targeted interventions. These should focus on improving preventive practices through education, providing skin-friendly antiseptics, and fostering a stronger culture of patient safety.

Hand washing with soap and water was the main method used by 54.7% of nurses before patient contact and 42.7% after touching the patient's environment. Although the combined use of both handwashing and alcohol-based hand rub was fairly common (peaking at 28%), a concerning 0.7-4% of nurses used neither method in various situations.

This preference for traditional handwashing aligns with findings from Iraqi ICU studies [18], likely reflecting ingrained habits and the availability of sinks. However, it contradicts international guidelines that recommend alcohol-based hand rub as the preferred method due to its superior efficacy and skin tolerance [27]. The low utilization of hand rub suggests barriers such as inadequate access, insufficient training, or persistent misconceptions. Although some nurses demonstrated good practice by using both methods, the consistent non-adherence by a small group echoes concerning findings from observational studies in Kurdistan [19], highlighting ongoing behavioral challenges likely driven by high workload and skin problems.

The pattern observed in this study shows that while nurses generally follow hand hygiene guidelines, the quality and effectiveness of their methods need significant improvement. Promoting alcohol-based hand rub as the preferred method is crucial. This can be achieved through ongoing education to correct misconceptions, ensuring hand rub is always available at all points of care, and providing skin-care products to reduce side effects. This comprehensive approach is essential for improving infection control in Iraqi hospitals.

The pattern observed in this study shows that while nurses generally follow hand hygiene guidelines, the quality and effectiveness of their methods need significant improvement. Promoting alcohol-based hand rub as the preferred method is crucial. This can be achieved through ongoing education to correct misconceptions, ensuring hand rub is always available at all points of care, and providing skin-care products to reduce side effects. This comprehensive approach is essential for improving infection control in Iraqi hospitals.

The study identified a critical triad of failure in hand hygiene adherence, driven by systemic barriers rather than individual negligence. The primary obstacles were high workload (76%) and lack of time (53.4%), confirming work pressure as a universal challenge [20-26]. Furthermore, a significant occupational health crisis was revealed, with over half of nurses reporting skin problems from both soap (50%) and antiseptic solutions (58%), and 62.7% suffering from dryness or cracking. This explains the preference for traditional handwashing and highlights harmful products as a major physical barrier [27]. These findings demonstrate that theoretical training alone is insufficient [29]. A successful intervention requires a fundamental, multi-dimensional approach addressing three core areas simultaneously: Human Resources to reduce workload through adequate staffing; Logistics to provide skin-compatible antiseptics and moisturizers; and Organizational Culture to foster strong leadership and a supportive, blame-free environment. Ultimately, resolving this crisis depends on recognizing it as a systemic failure, requiring committed resource allocation and managerial action to create a sustainable solution.

Among all demographic and professional variables examined, gender was the only significant predictor of hand hygiene compliance, with male nurses showing notably lower adherence scores than females. However, it is important to interpret this finding with caution. The small number of male participants in our sample (17.3%) limits the generalizability and stability of this result. This finding aligns with regional studies in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait [21, 27], indicating that deeply rooted sociocultural and attitudinal factors may contribute to this ongoing gender disparity in compliance. Conversely, the absence of significance for other characteristics, such as age and education, agrees with research from Malawi [23], emphasizing that organizational and environmental barriers, like high workload and skin problems, have a much stronger impact on hand hygiene behavior than most personal traits. This pattern suggests that in resource-limited settings, systemic issues affect all staff equally, with gender being one of the few individual factors that continue to influence behavior despite these overwhelming contextual challenges.

The findings offer critical insights for strengthening preventive care. First, interventions must move beyond basic education to address the systemic barriers of workload and skin health. This includes advocating for adequate staffing and providing skin-friendly hand rubs and moisturizers. Second, promoting alcohol-based hand rubs as the gold standard is essential for improving practice quality. Finally, fostering a supportive organizational culture with strong leadership is crucial. For midwifery practice, these measures are vital to protect both healthcare workers and vulnerable patients, particularly mothers and newborns, from preventable infections.

This study has several limitations: the use of convenience sampling, which may limit the generalizability of the findings, and the cultural differences, which could have influenced nurses' understanding and responses to the questionnaires. Additionally, non-cooperation from some nurses due to workload or time constraints might have decreased the sample size and impacted data quality. Moreover, using self-report questionnaires may have introduced social desirability bias, as participants might not have reported information accurately out of concern about being judged. To address these limitations, efforts were made to minimize cultural impact by accurately translating the questionnaires into Arabic and consulting with a local advisor in Iraq. Increased cooperation was encouraged by motivating nurses and explaining the importance of the research. To reduce social desirability bias, anonymous data collection methods were used.

Conclusions

This study presents a complex view of hand hygiene adherence among nurses in Babylon, Iraq, characterized by situation-dependent compliance. Compliance was highest after risky exposures like contact with body fluids, but lowest in preventive moments such as before patient contact—showing nurses often prioritize self-protection over patient safety. The main barriers were systemic, including high workload and skin issues caused by antiseptics. Gender was a significant independent predictor, with male nurses consistently showing lower adherence. This is worsened by the common use of less effective handwashing with soap instead of preferred alcohol-based rubs.

Improving adherence requires a comprehensive approach that addresses organizational barriers such as workload, ensures the provision of skin-friendly products, conducts targeted training especially for male nurses, and promotes a strong culture of safety for both patients and staff.

Success depends on committed leadership to foster an environment where hand hygiene becomes an unavoidable standard.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in strict accordance with ethical principles, which involved obtaining formal ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUK.REC.1404.137) and securing the necessary permissions from relevant university and hospital administrations. The purpose and procedures of the research were thoroughly explained to all participating head nurses and nurses, from whom informed consent was obtained. The confidentiality of all collected data was guaranteed, participation was entirely voluntary, and a summary of the findings was made available to both participants and relevant officials upon request.

Acknowledgments

This study was derived from the first author's Master of Science in Medical-Surgical Nursing thesis. The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the nurses who participated in this study, as well as to the administrators of the teaching hospitals in Babylon city for their cooperation and support in facilitating data collection. We also extend our thanks to the International Affairs Office of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences for their assistance.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' Contributions

Abdulabbas Abdulhasan K: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft Preparation.

Mohammed Aldoori N: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – Review & Editing.

Valiee S: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing – Review & Editing.

All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Artificial Intelligence Utilization for Article Writing

We used artificial intelligence chatbots to improve the readability and language of the work.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Type of Study: Orginal research |

Subject:

Nursing

References

1. 1. World Health Organization. Report on the Burden of Endemic Health Care-Associated Infection Worldwide: Clean Care Is Safer Care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

2. Apanga S, Adda J, Issahaku M, Amofa J, Mawufemor KRA, Bugr S. Post-Operative Surgical Site Infection in a Surgical Ward of a Tertiary Care Hospital in Northern Ghana. International Journal of Research in Health Sciences. 2014;2(2):178-85.

3. Allegranzi B, Nejad SB, Combescure C, Graafmans W, Attar H, Donaldson L, et al. Burden of Endemic Health-Care-Associated Infection in Developing Countries: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Lancet. 2011;377(9761):228-41. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61458-4] [PMID]

4. Kambale G, Feasey N, Henrion MYR, Noah P, Musaya J. Healthcare-Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Use in Surgical Wards of a Large Urban Central Hospital in Blantyre, Malawi: A Point Prevalence Survey. Infection Prevention in Practice. 2021;3(2):100163. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infpip.2021.100163] [PMID]

5. Mbim EN, Mboto CI, Agbo BE. A Review of Nosocomial Infections in Sub-Saharan Africa. British Microbiology Research Journal. 2016;15(1):1-11. [https://doi.org/10.9734/BMRJ/2016/25895]

6. Nair A, Steinberg WJ, Habib T, Saeed H, Raubenheimer JE. Prevalence of Healthcare-Associated Infection at a Tertiary Hospital in the Northern Cape Province, South Africa. South African Family Practice. 2018;60(5):162-7. [https://doi.org/10.1080/20786190.2018.1487211]

7. Hearn P, Miliya T, Seng S, Ngoun C, Day NPJ, Lubell Y, et al. Prospective Surveillance of Healthcare Associated Infections in a Cambodian Pediatric Hospital. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control. 2017;6:16. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-017-0176-1]

8. Nejad SB, Allegranzi B, Syed SB, Ellis B, Pittet D. Health-Care-Associated Infection in Africa: A Systematic Review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2011;89(10):757-65. [https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.11.088179] [PMID]

9. Al-Kharkhi MA, Zeiny SM, Ali SM. Nosocomial Infections in a Surgical Floor of the General Ba'qubah Hospital; Iraq. Journal of the Faculty of Medicine Baghdad. 2016;58(1):51-7. [https://doi.org/10.32007/med.1936/jfacmedbagdad.v58i1.11]

10. Bellissimo-Rodrigues F, Bellissimo-Rodrigues WT, Menegueti MG. Selfishness Among Healthcare Workers and Nosocomial Infections: A Causal Relationship? Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2014;47(4):407-8. [https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0191-2014] [PMID]

11. World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

12. Curtis V, Cairncross S. Effect of Washing Hands With Soap on Diarrhoea Risk in the Community: A Systematic Review. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2003;3(5):275-81. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00606-6] [PMID]

13. Ejemot-Nwadiaro RI, Ehiri JE, Arikpo D, Meremikwu MM, Critchley JA. Hand Washing Promotion for Preventing Diarrhoea. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;9:CD004265. [https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004265.pub3] [PMID]

14. Ellingson K, Haas JP, Aiello AE, Kusek L, Maragakis LL, Olmsted RN, et al. Strategies to Prevent Healthcare-Associated Infections through Hand Hygiene. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2014;35(8):937-60. [https://doi.org/10.1086/677145] [PMID]

15. World Health Organization. A Guide to the Implementation of the WHO Multimodal Hand Hygiene Improvement Strategy. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

16. Nouri B, Hajizadeh M, Bahmanpour K, Sadafi M, Rezaei S, Valiee S. Hand Hygiene Adherence Among Iranian Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nursing Practice Today. 2021;8(4):269-80. [https://doi.org/10.18502/npt.v8i1.4488]

17. Hafedh Ahmed S, Salman Khudhair AK, Haghani S, Najafi Ghezeljeh T. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Iraqi Intensive Care Nursing Staff Regarding Pressure Ulcer Prevention. Journal of Client-Centered Nursing Care. 2024;10(2):91-100. [https://doi.org/10.32598/JCCNC.10.2.463]

18. Muqdad IM, Khudhair AK, Haghani S, Najafi Ghezeljeh T. Investigating the Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Iraqi Intensive Care Nursing Staff Regarding Hand Hygiene. Journal of Client-Centered Nursing Care. 2024;10(1):65-74. [https://doi.org/10.32598/JCCNC.10.1.464]

19. Moued I, Haweizy RM, Miran LS, Mohammed MG, von Schreeb J, Älgå A. Observational Study of Hand Hygiene Compliance at a Trauma Hospital in Iraqi Kurdistan. Journal of Surgery. 2021;4(3):794-802. [https://doi.org/10.3390/j4040054]

20. World Health Organization. Monitoring Tools - Hand Hygiene [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024]. [https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/infection-prevention-control/hand-hygiene/monit]

21. Al Mohaithef M. Assessing Hand Hygiene Practices Among Nurses in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Open Public Health Journal. 2020;13(1):220-6. [DOI:10.2174/1874944502013010220]

22. Daulay FC, Sudiro S, Amirah A. Management Analysis of Infection Prevention: Nurses' Compliance in Implementing Hand Hygiene in the Inventories of Rantauprapat Hospital. Journal of Scientific Research in Medical and Biological Sciences. 2021;2(2):42-9. [https://doi.org/10.47631/jsrmbs.v2i1.218]

23. Nzanga M, Panulo M, Morse T, Chidziwisano K. Adherence to Hand Hygiene Among Nurses and Clinicians at Chiradzulu District Hospital, Southern Malawi. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(17):10981. [https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710981] [PMID]

24. Sandbekken IH, Hermansen Å, Utne I, Grov EK, Løyland B. Students' Observations of Hand Hygiene Adherence in 20 Nursing Home Wards, During the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2022;22(1):156. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07133-8] [PMID]

25. Sandbøl SG, Glassou EN, Ellermann-Eriksen S, Haagerup A. Hand Hygiene Compliance Among Healthcare Workers Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. American Journal of Infection Control. 2022;50(7):719-23. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2022.01.013] [PMID]

26. Umar H, Geremew A, Worku Kassie T, Dirirsa G, Bayu K, Mengistu DA, et al. Hand Hygiene Compliance and Associated Factors Among Nurses Working in Public Hospitals of Hararghe Zones, Oromia Region, Eastern Ethiopia. Frontiers in Public Health. 2022;10:1032167. [https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1032167] [PMID]

27. Al-Anazi S, Al-Dhefeery N, Al-Hjaili R, Al-Duwaihees A, Al-Mutairi A, Al-Saeedi R, et al. Compliance with Hand Hygiene Practices Among Nursing Staff in Secondary Healthcare Hospitals in Kuwait. BMC Health Services Research. 2022;22(1):1325. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08697-6] [PMID]

28. Kassim ZA, Al-Mulaabed SW, Younis SW, Abutiheen AA. Infection Prevention and Control Measures for COVID-19 Among Medical Staff in Nineveh Governorate, Iraq. Journal of Contemporary Medical Sciences. 2020;6(4):170-5. [https://doi.org/10.22317/jcms.v6i4.820]

29. Alhodaithy N, Alshagrawi S. Predictors of Hand Hygiene Attitudes Among Saudi Healthcare Workers of the Intensive Care Unit in Saudi Arabia. Scientific Reports. 2024;14(1):19857. [https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70806-8] [PMID]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |