Preventive Care in Nursing and Midwifery Journal

Volume 15, Issue 4 (12-2025)

Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J 2025, 15(4): 0-0 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: Confidentiality and Anonymity, Principle of Beneficence, respect for authonomy

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Jimmy Agada J, Wankasi Idubamo H. Dissemination and Implementation Strategies for Doula Support Services in Bayelsa State, Nigeria: A Quantitative Cross-Sectional Survey. Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J 2025; 15 (4)

URL: http://nmcjournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-998-en.html

URL: http://nmcjournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-998-en.html

Department of Maternal and Child Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing Sciences, Niger Delta University, Wilberforce Island Bayelsa State, Nigeria. , jessicaagada@ndu.edu.ng

Keywords: Doula Support Services, Maternal Health Services, Program Implementation, Health Knowledge, Nigeria

Full-Text [PDF 895 kb]

(5 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (49 Views)

NGO = Non-Governmental Organization; CSO = Civil Society Organization; FBO = Faith-Based Organization

Table 3. Factors Associated with Knowledge Level on the Dissemination and Implementation of Doula Support Service (N = 101)

Full-Text: (2 Views)

Introduction

Maternal and newborn outcomes have improved globally over time; however, preventable morbidity and mortality remain disproportionately concentrated in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), with Nigeria contributing substantially to the remaining burden[1]. Within Nigeria, persistent gaps in skilled attendance and the quality of intrapartum care continue to undermine maternal–newborn health gains [2]. These service delivery constraints occur alongside increasing pressures on the health workforce, particularly for nurses and midwives, driven by weak retention conditions and sustained out-migration, which reduce the capacity of facilities to deliver continuous, person-centred support during pregnancy and childbirth[3]. In riverine and hard-to-reach settings such as Bayelsa State, geographic barriers and transport limitations further intensify challenges in providing timely, respectful, and responsive maternity care.

In addition to clinical interventions and facility access, the experience of care has become a recognised determinant of childbirth outcomes and women’s satisfaction. Evidence indicates that continuous, non-clinical support during labour is associated with improved experiences and favourable obstetric outcomes, including a higher likelihood of spontaneous vaginal birth and reduced caesarean and instrumental birth rates across diverse contexts[4]. Consistent with this evidence base, the World Health Organization emphasises respectful maternity care and a positive childbirth experience as essential quality domains of intrapartum care [3]

Doula support services represent a structured, evidence-informed approach to strengthening continuous support. Doulas are trained, non-clinical personnel who provide continuous emotional, informational, and physical support to women and families during pregnancy, labour, and the immediate postpartum period. Continuous labour support delivered by doulas or trained companions has been associated with improved satisfaction and reduced use of certain interventions, particularly in contexts where maternity wards are overburdened and continuous midwifery presence may be difficult to sustain [4, 5]. As such, doula services are increasingly positioned as an implementable, person-centred complement that strengthens supportive care without replacing the clinical roles and decision-making responsibilities of skilled birth attendants.

Despite the global evidence supporting continuous non-clinical support, doula support services are not yet systematically embedded within Bayelsa State’s public maternity care system, and a clear implementation pathway for routine integration remains underdeveloped. This constitutes a measurable implementation gap in which three related deficiencies are evident. First, there is no locally tailored, stakeholder-informed implementation blueprint that clearly specifies leadership responsibilities, role boundaries between doulas and clinical teams, workflow integration at both facility and community levels, referral and escalation procedures, documentation standards, and supervision or quality assurance mechanisms. Second, there is insufficient quantitative evidence indicating which dissemination channels and implementation strategies key stakeholders, such as facility managers, maternity care providers, and regulatory or policy actors, consider most feasible, acceptable, appropriate, and impactful for integrating doula support into routine maternity care. Third, accountability structures for implementation remain inconsistently specified, particularly regarding who leads dissemination and who is responsible for facility-level adoption, supervision, and sustainability; this increases the likelihood of fragmented and non-standardised adoption. Collectively, these gaps constrain rational prioritisation of limited resources and slow the translation of an evidence-supported support model into routine practice in Bayelsa State.

The existing literature establishes the burden of maternal mortality and persistent quality gaps in LMICs, including Nigeria [1, 6] and it demonstrates that continuous support during labour can improve both experience and selected clinical outcomes [4] Nevertheless, effectiveness evidence alone does not ensure uptake at scale. Implementation frequently falters when roles are poorly specified, leadership engagement is inadequate, workflows are not adapted to the local context, training and supervision are insufficient, and monitoring systems are absent or inconsistently applied. Accordingly, the central knowledge gap in Bayelsa State is not whether continuous support can be beneficial, but rather which dissemination and implementation strategies stakeholders judge workable for this setting, and how those strategies should be structured, governed, and sustained within routine maternity services. Addressing this gap requires stakeholder-informed evidence on feasible strategy packages and leadership structures that can inform a practical implementation roadmap.

To address the identified implementation gap and ensure a structured pathway from evidence to routine practice, this study is guided by three complementary implementation-science frameworks selected for their distinct and synergistic roles in implementation planning. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) was selected as the determinant framework because it provides a comprehensive structure for assessing why implementation succeeds or fails across domains, including intervention characteristics, the outer setting, the inner setting, characteristics of individuals, and the implementation process [7]. In this study, CFIR informs the questionnaire domains and the interpretation of findings by mapping stakeholder responses to determinants such as policy integration and community demand generation within the outer setting, facility readiness and leadership engagement within the inner setting, stakeholder knowledge and beliefs about doula roles within characteristics of individuals, and planning, engagement, and iterative learning within the process domain. The RE-AIM framework (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) was selected because it supports pragmatic planning and evaluation, ensuring that interventions are designed for population impact and sustainability rather than short-term adoption alone [8, 9]. In practice, RE-AIM informs how this study conceptualises the pathway from dissemination to sustained integration by ensuring that assessed strategies address population reach through appropriate communication channels, organisational adoption by relevant facilities and governance structures, implementation fidelity through training, supervision, referral pathways, and documentation, and maintenance through policy embedding, routine monitoring, and continuous improvement mechanisms.

The ERIC compilation (Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change) was selected because it provides a standardised taxonomy of implementation strategies that can be operationalised and compared across settings [10, 11]. In this study, ERIC is used to define and group strategy options assessed in the survey, such as training and education, developing implementation blueprints, adapting to context, strengthening stakeholder interrelationships, and the use of audit and feedback so that results can directly translate into a prioritised, Bayelsa-specific strategy package.

Objectives

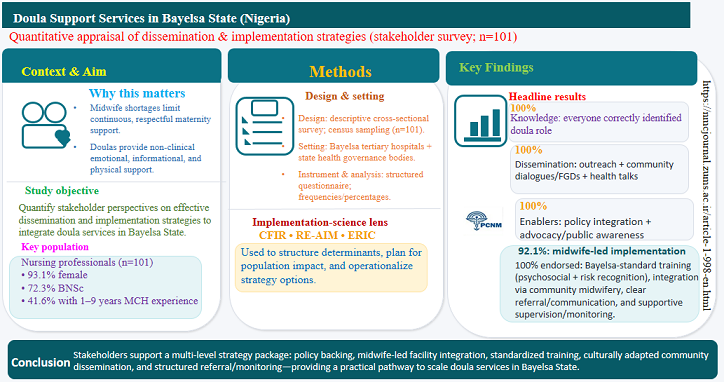

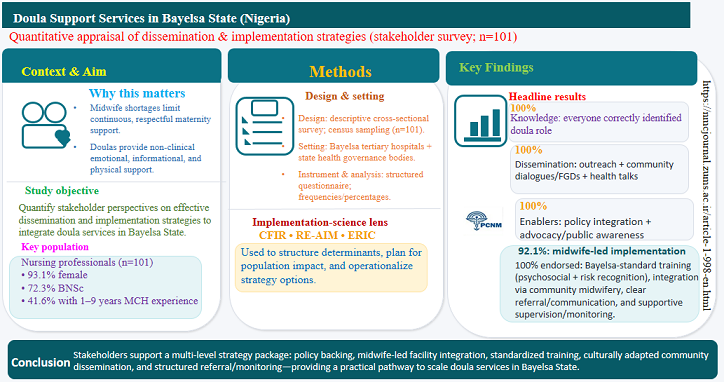

This study aimed to quantitatively appraise the knowledge and perspectives of key stakeholders to determine effective strategies for the dissemination and sustainable implementation of doula support services within the maternal healthcare system of Bayelsa State, Nigeria.

Methods

Study Design

This study adopted a descriptive cross-sectional survey design to generate quantitative evidence on stakeholders’ perspectives regarding effective dissemination and implementation strategies for integrating doula support services within Bayelsa State’s maternity care system. A cross-sectional approach was considered appropriate because it enables the systematic capture of perceptions, preferences, and institutional readiness indicators at a single point in time across multiple stakeholder groups and settings, thereby supporting priority-setting for implementation planning. This research design has been used by other researchers to explore similar areas in line with the phenomenon under study [4].

Study Settings

The study was conducted in Bayelsa State, Nigeria, within selected tertiary health institutions (Federal Medical Centre, Yenagoa, and Niger Delta University Teaching Hospital, Okolobiri) and relevant regulatory/administrative health structures such as the Bayelsa State Ministry of Health and the Bayelsa State Hospital Management Board as involved in maternal and newborn care governance and service delivery.

These settings were selected because they represent the major decision-making and service delivery nodes through which doula support services would be disseminated, adopted, supervised, and sustained if integrated into routine care. Selection bias was assessed by examining whether the chosen study settings and recruitment procedures could produce a sample whose views differ from the broader stakeholder population for doula dissemination and implementation in Bayelsa State. The study purposively selected two tertiary hospitals and two key governance/regulatory bodies to maximize policy and implementation relevance, but this may limit external representativeness because primary care, private, and community maternity stakeholders were not included, potentially skewing strategy preferences toward what is feasible in tertiary/administrative contexts. At the participant level, a census approach with predefined eligibility criteria, a four-week weekday data-collection period, immediate questionnaire retrieval, and a 100% return rate reduced non-response and improved coverage within the selected institutions. Nonetheless, some residual bias could arise if eligible staff were missed due to workload, shifts, postings, gatekeeping, or if eligibility rules excluded relevant stakeholder categories. Overall, the risk of selection bias is judged low within the defined institutional sampling frame but moderate for generalizability to the wider Bayelsa maternal and newborn care system.

Participants

The total participants of this study were 101, comprising key maternal and newborn health stakeholders drawn from selected tertiary institutions and relevant regulatory and administrative health structures in Bayelsa State, Nigeria. Specifically, midwives working in maternity wards at the Federal Medical Centre (FMC), Yenagoa (68 midwives) and Niger Delta University Teaching Hospital (NDUTH), Okolobiri (25 midwives) were included. In addition, 8 nursing directors were recruited, including one each from the Bayelsa State Ministry of Health and the Bayelsa State Hospital Management Board, as well as three nursing directors each from FMC Yenagoa and NDUTH Okolobiri. Inclusion criteria are critical for defining the study's scope, enhancing validity, and ensuring reproducibility. Inclusion criteria for the selection of respondents for this study were as follows: respondents must be between 25 and 60 years of age, must have a minimum of three (3) years’ experience post-qualification, and must be willing to participate in the study. While the exclusion criteria were midwives not working in the maternity units of the hospitals in this study, and those who were terminally sick.

Sampling Methods

A census sampling method (total population sampling) was employed, with the entire target population included in the study. Consequently, the total sample size was one hundred and one (101) respondents. This approach was selected to ensure full population inclusion, reduce sampling error, and enhance completeness of data collection as well as policy relevance within the study context.

Data Collection

Following the receipt of a letter of introduction from the Dean, Faculty of Nursing Sciences, Niger Delta University, Wilberforce Island, Bayelsa State, and ethical approvals from the research and ethics committees of the Federal Medical Centre, Yenagoa; Niger Delta University Teaching Hospital, Okolobiri; the Bayelsa State Ministry of Health; and the Bayelsa State Hospitals Management Board, the researcher proceeded to the study sites to commence data collection. The researcher formally approached the head nurses of the participating facilities and conducted appropriate introductions to facilitate access and coordination within each setting.

Two research assistants were trained to support the data collection exercise. Their training covered the purpose and objectives of the study, the procedures for engaging respondents appropriately, and the correct approach to administering and retrieving responses. The assistants were selected based on their ability to communicate effectively in English. The researcher and trained assistants explained the purpose of the study to eligible respondents and obtained information only from those who voluntarily consented to participate.

Data collection was conducted on weekdays (Mondays to Fridays) during official working hours and scheduled before the commencement of nursing and medical rounds to minimize interruptions and distractions. The data collection period spanned four weeks to ensure that all eligible respondents, including those who were on annual leave, had sufficient opportunity to participate. All administered forms were retrieved immediately after completion, resulting in a complete return rate of 100%.

Variables

In this study, sex, age, educational status, and work experience constitute the independent variables because they are respondent characteristics that may influence how stakeholders appraise doula support services. The dependent variables are the outcomes being measured in relation to these predictors, namely, stakeholders’ knowledge of doula support services, and stakeholders’ effective dissemination and implementation strategies for doula support services.

Measurement Tools

The measurement tool for this study was a researcher-developed structured questionnaire designed to quantitatively assess stakeholders’ perspectives on the dissemination and implementation of doula support services in Bayelsa State. The questionnaire was organized into four sections. Section A assessed respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics and contained four (4) items. Section B measured stakeholders’ knowledge of doula support services using one (1) item. Section C measured stakeholders’ proposed dissemination strategies for doula support services using six (6) items, while Section D assessed stakeholders’ proposed implementation strategies using thirteen (13) items. All questions were closed-ended and rated on a four-point Likert scale (Strongly Agree, Agree, Disagree, and Strongly Disagree) to ensure standardized responses and support quantitative analysis.

To ensure the tool measured what it was intended to measure, the questionnaire was subjected to face and content validity procedures. Reliability was assessed using a test-retest method with 38 participants, in which the same instrument was administered twice to the same group. Internal consistency reliability was further established using Cronbach’s alpha, yielding a coefficient of 0.93, which indicates that the questionnaire was highly reliable for the measurement of the study constructs.

Data Analysis

For this study, the researchers utilized descriptive statistics, including frequency and percentage, and inferential statistics (chi-square) for the test of hypotheses.

Result

A total of 101 nurses participated in this study. Their socio-demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. Most participants (73.3%) were between 25 and 51 years old, the vast majority (93.1%) were female, the primary educational qualification was a Bachelor of Nursing Science (72.3%), and the most common work experience in maternal and child health services was 1 to 9 years (41.6%).

In the assessment of foundational knowledge, all participants (100%) correctly identified the primary role of doulas as trained non-clinical personnel who provide physical, emotional, and informational support during pregnancy, labour, and the puerperium.

This finding indicates a universal and uniform understanding of the core definition and function of a doula among the study population.

Table 2 presents the proposed strategies for the dissemination and implementation of doula support services. In the domain of dissemination, there was strong consensus (98% to 100%) on starting with community health talks, using dialogues and focus groups to foster local ownership, tailoring messages culturally and linguistically (e.g., translation into Ijaw and Nembe languages), and employing a mixed-media approach (community radio, mobile outreach). In the domain of implementation, very strong support (97% to 100%) was found for systemic enablers such as the need for multi-stakeholder engagement, government policy, and advocacy and public awareness. Operational mechanisms like standardized, context-tailored training with an emphasis on psychosocial support, basic clinical risk identification training, integrating doulas into public facilities via a community midwifery scheme, establishing clear referral and communication pathways, and providing ongoing support and monitoring were also unanimously endorsed (100%). Regarding leadership of the process, primary responsibility was assigned to midwives (92.1% agreement), while views were more divided on the leadership roles of hospital management (54.5% agreement) and community leaders (46.5% agreement). Partnership with NGOs, CSOs, and FBOs was also widely supported (97%) for resource provision and capacity building.

An assessment of factors associated with knowledge level concerning the dissemination and implementation of doula services (Table 3) revealed that among the variables of sex, age, educational level, and years of experience, only years of work experience showed a statistically significant association with good knowledge (p = 0.045). Specifically, nurses with more than 18 years of experience were significantly more likely to have good knowledge (Odds Ratio: 1.13, 95% CI: 0.81–0.96). The other variables were not statistically significant.

Maternal and newborn outcomes have improved globally over time; however, preventable morbidity and mortality remain disproportionately concentrated in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), with Nigeria contributing substantially to the remaining burden[1]. Within Nigeria, persistent gaps in skilled attendance and the quality of intrapartum care continue to undermine maternal–newborn health gains [2]. These service delivery constraints occur alongside increasing pressures on the health workforce, particularly for nurses and midwives, driven by weak retention conditions and sustained out-migration, which reduce the capacity of facilities to deliver continuous, person-centred support during pregnancy and childbirth[3]. In riverine and hard-to-reach settings such as Bayelsa State, geographic barriers and transport limitations further intensify challenges in providing timely, respectful, and responsive maternity care.

In addition to clinical interventions and facility access, the experience of care has become a recognised determinant of childbirth outcomes and women’s satisfaction. Evidence indicates that continuous, non-clinical support during labour is associated with improved experiences and favourable obstetric outcomes, including a higher likelihood of spontaneous vaginal birth and reduced caesarean and instrumental birth rates across diverse contexts[4]. Consistent with this evidence base, the World Health Organization emphasises respectful maternity care and a positive childbirth experience as essential quality domains of intrapartum care [3]

Doula support services represent a structured, evidence-informed approach to strengthening continuous support. Doulas are trained, non-clinical personnel who provide continuous emotional, informational, and physical support to women and families during pregnancy, labour, and the immediate postpartum period. Continuous labour support delivered by doulas or trained companions has been associated with improved satisfaction and reduced use of certain interventions, particularly in contexts where maternity wards are overburdened and continuous midwifery presence may be difficult to sustain [4, 5]. As such, doula services are increasingly positioned as an implementable, person-centred complement that strengthens supportive care without replacing the clinical roles and decision-making responsibilities of skilled birth attendants.

Despite the global evidence supporting continuous non-clinical support, doula support services are not yet systematically embedded within Bayelsa State’s public maternity care system, and a clear implementation pathway for routine integration remains underdeveloped. This constitutes a measurable implementation gap in which three related deficiencies are evident. First, there is no locally tailored, stakeholder-informed implementation blueprint that clearly specifies leadership responsibilities, role boundaries between doulas and clinical teams, workflow integration at both facility and community levels, referral and escalation procedures, documentation standards, and supervision or quality assurance mechanisms. Second, there is insufficient quantitative evidence indicating which dissemination channels and implementation strategies key stakeholders, such as facility managers, maternity care providers, and regulatory or policy actors, consider most feasible, acceptable, appropriate, and impactful for integrating doula support into routine maternity care. Third, accountability structures for implementation remain inconsistently specified, particularly regarding who leads dissemination and who is responsible for facility-level adoption, supervision, and sustainability; this increases the likelihood of fragmented and non-standardised adoption. Collectively, these gaps constrain rational prioritisation of limited resources and slow the translation of an evidence-supported support model into routine practice in Bayelsa State.

The existing literature establishes the burden of maternal mortality and persistent quality gaps in LMICs, including Nigeria [1, 6] and it demonstrates that continuous support during labour can improve both experience and selected clinical outcomes [4] Nevertheless, effectiveness evidence alone does not ensure uptake at scale. Implementation frequently falters when roles are poorly specified, leadership engagement is inadequate, workflows are not adapted to the local context, training and supervision are insufficient, and monitoring systems are absent or inconsistently applied. Accordingly, the central knowledge gap in Bayelsa State is not whether continuous support can be beneficial, but rather which dissemination and implementation strategies stakeholders judge workable for this setting, and how those strategies should be structured, governed, and sustained within routine maternity services. Addressing this gap requires stakeholder-informed evidence on feasible strategy packages and leadership structures that can inform a practical implementation roadmap.

To address the identified implementation gap and ensure a structured pathway from evidence to routine practice, this study is guided by three complementary implementation-science frameworks selected for their distinct and synergistic roles in implementation planning. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) was selected as the determinant framework because it provides a comprehensive structure for assessing why implementation succeeds or fails across domains, including intervention characteristics, the outer setting, the inner setting, characteristics of individuals, and the implementation process [7]. In this study, CFIR informs the questionnaire domains and the interpretation of findings by mapping stakeholder responses to determinants such as policy integration and community demand generation within the outer setting, facility readiness and leadership engagement within the inner setting, stakeholder knowledge and beliefs about doula roles within characteristics of individuals, and planning, engagement, and iterative learning within the process domain. The RE-AIM framework (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) was selected because it supports pragmatic planning and evaluation, ensuring that interventions are designed for population impact and sustainability rather than short-term adoption alone [8, 9]. In practice, RE-AIM informs how this study conceptualises the pathway from dissemination to sustained integration by ensuring that assessed strategies address population reach through appropriate communication channels, organisational adoption by relevant facilities and governance structures, implementation fidelity through training, supervision, referral pathways, and documentation, and maintenance through policy embedding, routine monitoring, and continuous improvement mechanisms.

The ERIC compilation (Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change) was selected because it provides a standardised taxonomy of implementation strategies that can be operationalised and compared across settings [10, 11]. In this study, ERIC is used to define and group strategy options assessed in the survey, such as training and education, developing implementation blueprints, adapting to context, strengthening stakeholder interrelationships, and the use of audit and feedback so that results can directly translate into a prioritised, Bayelsa-specific strategy package.

Objectives

This study aimed to quantitatively appraise the knowledge and perspectives of key stakeholders to determine effective strategies for the dissemination and sustainable implementation of doula support services within the maternal healthcare system of Bayelsa State, Nigeria.

Methods

Study Design

This study adopted a descriptive cross-sectional survey design to generate quantitative evidence on stakeholders’ perspectives regarding effective dissemination and implementation strategies for integrating doula support services within Bayelsa State’s maternity care system. A cross-sectional approach was considered appropriate because it enables the systematic capture of perceptions, preferences, and institutional readiness indicators at a single point in time across multiple stakeholder groups and settings, thereby supporting priority-setting for implementation planning. This research design has been used by other researchers to explore similar areas in line with the phenomenon under study [4].

Study Settings

The study was conducted in Bayelsa State, Nigeria, within selected tertiary health institutions (Federal Medical Centre, Yenagoa, and Niger Delta University Teaching Hospital, Okolobiri) and relevant regulatory/administrative health structures such as the Bayelsa State Ministry of Health and the Bayelsa State Hospital Management Board as involved in maternal and newborn care governance and service delivery.

These settings were selected because they represent the major decision-making and service delivery nodes through which doula support services would be disseminated, adopted, supervised, and sustained if integrated into routine care. Selection bias was assessed by examining whether the chosen study settings and recruitment procedures could produce a sample whose views differ from the broader stakeholder population for doula dissemination and implementation in Bayelsa State. The study purposively selected two tertiary hospitals and two key governance/regulatory bodies to maximize policy and implementation relevance, but this may limit external representativeness because primary care, private, and community maternity stakeholders were not included, potentially skewing strategy preferences toward what is feasible in tertiary/administrative contexts. At the participant level, a census approach with predefined eligibility criteria, a four-week weekday data-collection period, immediate questionnaire retrieval, and a 100% return rate reduced non-response and improved coverage within the selected institutions. Nonetheless, some residual bias could arise if eligible staff were missed due to workload, shifts, postings, gatekeeping, or if eligibility rules excluded relevant stakeholder categories. Overall, the risk of selection bias is judged low within the defined institutional sampling frame but moderate for generalizability to the wider Bayelsa maternal and newborn care system.

Participants

The total participants of this study were 101, comprising key maternal and newborn health stakeholders drawn from selected tertiary institutions and relevant regulatory and administrative health structures in Bayelsa State, Nigeria. Specifically, midwives working in maternity wards at the Federal Medical Centre (FMC), Yenagoa (68 midwives) and Niger Delta University Teaching Hospital (NDUTH), Okolobiri (25 midwives) were included. In addition, 8 nursing directors were recruited, including one each from the Bayelsa State Ministry of Health and the Bayelsa State Hospital Management Board, as well as three nursing directors each from FMC Yenagoa and NDUTH Okolobiri. Inclusion criteria are critical for defining the study's scope, enhancing validity, and ensuring reproducibility. Inclusion criteria for the selection of respondents for this study were as follows: respondents must be between 25 and 60 years of age, must have a minimum of three (3) years’ experience post-qualification, and must be willing to participate in the study. While the exclusion criteria were midwives not working in the maternity units of the hospitals in this study, and those who were terminally sick.

Sampling Methods

A census sampling method (total population sampling) was employed, with the entire target population included in the study. Consequently, the total sample size was one hundred and one (101) respondents. This approach was selected to ensure full population inclusion, reduce sampling error, and enhance completeness of data collection as well as policy relevance within the study context.

Data Collection

Following the receipt of a letter of introduction from the Dean, Faculty of Nursing Sciences, Niger Delta University, Wilberforce Island, Bayelsa State, and ethical approvals from the research and ethics committees of the Federal Medical Centre, Yenagoa; Niger Delta University Teaching Hospital, Okolobiri; the Bayelsa State Ministry of Health; and the Bayelsa State Hospitals Management Board, the researcher proceeded to the study sites to commence data collection. The researcher formally approached the head nurses of the participating facilities and conducted appropriate introductions to facilitate access and coordination within each setting.

Two research assistants were trained to support the data collection exercise. Their training covered the purpose and objectives of the study, the procedures for engaging respondents appropriately, and the correct approach to administering and retrieving responses. The assistants were selected based on their ability to communicate effectively in English. The researcher and trained assistants explained the purpose of the study to eligible respondents and obtained information only from those who voluntarily consented to participate.

Data collection was conducted on weekdays (Mondays to Fridays) during official working hours and scheduled before the commencement of nursing and medical rounds to minimize interruptions and distractions. The data collection period spanned four weeks to ensure that all eligible respondents, including those who were on annual leave, had sufficient opportunity to participate. All administered forms were retrieved immediately after completion, resulting in a complete return rate of 100%.

Variables

In this study, sex, age, educational status, and work experience constitute the independent variables because they are respondent characteristics that may influence how stakeholders appraise doula support services. The dependent variables are the outcomes being measured in relation to these predictors, namely, stakeholders’ knowledge of doula support services, and stakeholders’ effective dissemination and implementation strategies for doula support services.

Measurement Tools

The measurement tool for this study was a researcher-developed structured questionnaire designed to quantitatively assess stakeholders’ perspectives on the dissemination and implementation of doula support services in Bayelsa State. The questionnaire was organized into four sections. Section A assessed respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics and contained four (4) items. Section B measured stakeholders’ knowledge of doula support services using one (1) item. Section C measured stakeholders’ proposed dissemination strategies for doula support services using six (6) items, while Section D assessed stakeholders’ proposed implementation strategies using thirteen (13) items. All questions were closed-ended and rated on a four-point Likert scale (Strongly Agree, Agree, Disagree, and Strongly Disagree) to ensure standardized responses and support quantitative analysis.

To ensure the tool measured what it was intended to measure, the questionnaire was subjected to face and content validity procedures. Reliability was assessed using a test-retest method with 38 participants, in which the same instrument was administered twice to the same group. Internal consistency reliability was further established using Cronbach’s alpha, yielding a coefficient of 0.93, which indicates that the questionnaire was highly reliable for the measurement of the study constructs.

Data Analysis

For this study, the researchers utilized descriptive statistics, including frequency and percentage, and inferential statistics (chi-square) for the test of hypotheses.

Result

A total of 101 nurses participated in this study. Their socio-demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. Most participants (73.3%) were between 25 and 51 years old, the vast majority (93.1%) were female, the primary educational qualification was a Bachelor of Nursing Science (72.3%), and the most common work experience in maternal and child health services was 1 to 9 years (41.6%).

In the assessment of foundational knowledge, all participants (100%) correctly identified the primary role of doulas as trained non-clinical personnel who provide physical, emotional, and informational support during pregnancy, labour, and the puerperium.

This finding indicates a universal and uniform understanding of the core definition and function of a doula among the study population.

Table 2 presents the proposed strategies for the dissemination and implementation of doula support services. In the domain of dissemination, there was strong consensus (98% to 100%) on starting with community health talks, using dialogues and focus groups to foster local ownership, tailoring messages culturally and linguistically (e.g., translation into Ijaw and Nembe languages), and employing a mixed-media approach (community radio, mobile outreach). In the domain of implementation, very strong support (97% to 100%) was found for systemic enablers such as the need for multi-stakeholder engagement, government policy, and advocacy and public awareness. Operational mechanisms like standardized, context-tailored training with an emphasis on psychosocial support, basic clinical risk identification training, integrating doulas into public facilities via a community midwifery scheme, establishing clear referral and communication pathways, and providing ongoing support and monitoring were also unanimously endorsed (100%). Regarding leadership of the process, primary responsibility was assigned to midwives (92.1% agreement), while views were more divided on the leadership roles of hospital management (54.5% agreement) and community leaders (46.5% agreement). Partnership with NGOs, CSOs, and FBOs was also widely supported (97%) for resource provision and capacity building.

An assessment of factors associated with knowledge level concerning the dissemination and implementation of doula services (Table 3) revealed that among the variables of sex, age, educational level, and years of experience, only years of work experience showed a statistically significant association with good knowledge (p = 0.045). Specifically, nurses with more than 18 years of experience were significantly more likely to have good knowledge (Odds Ratio: 1.13, 95% CI: 0.81–0.96). The other variables were not statistically significant.

| Variable | Category | n | % |

| Age (years) | 25–33 | 27 | 26.7 |

| 34–42 | 26 | 25.7 | |

| 43–51 | 34 | 33.7 | |

| 52–60 | 14 | 13.9 | |

| Sex | Male | 7 | 6.9 |

| Female | 94 | 93.1 | |

| Educational qualification | Diploma | 14 | 13.9 |

| BNSc | 73 | 72.3 | |

| M.SC. | 12 | 11.9 | |

| Ph.D. | 2 | 2.0 | |

| Years of experience in maternal and child health services (years) | 1–9 | 42 | 41.6 |

| 10–18 | 27 | 26.7 | |

| 19–27 | 21 | 20.8 | |

| 28–35 | 11 | 10.9 |

BNSc = Bachelor of Nursing Science.

Table 2. Strategies for Dissemination and Implementation of Doula Support Services (N = 101)

Table 2. Strategies for Dissemination and Implementation of Doula Support Services (N = 101)

| Strategy Category and Item | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) |

| Dissemination Strategies | ||

| Effective programs should employ outreach strategies | 101 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Community dialogues and focus groups foster local ownership | 101 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Best to start with community health talks | 101 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Health messages should reflect local cultural beliefs/practices | 99 (98.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| Materials/talks should be translated (e.g., Ijaw, Nembe) and tailored to literacy levels | 100 (99.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Use a mixed-media approach (community radio, mobile outreach) | 99 (98.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| Implementation Strategies | ||

| Implementation requires engagement from multiple stakeholders | 100 (99.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Government policy is essential for integration into the health system | 101 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Advocacy and public awareness are necessary for successful implementation | 101 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Midwives should take a lead position in dissemination/implementation | 93 (92.1) | 8 (7.9) |

| Hospital management should take a lead position | 55 (54.5) | 46 (45.5) |

| Community leaders should take a lead position | 47 (46.5) | 54 (53.5) |

| Doulas should undergo standardized training tailored to Bayelsa | 101 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Doulas should receive basic clinical knowledge to identify maternal risks | 101 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Emotional/psychosocial support should be the primary focus of training | 101 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Integrate doulas into public facilities via community midwifery scheme | 101 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Establish clear referral/communication pathways with providers | 101 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Doulas should be supported and monitored | 101 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Local NGOs/CSOs/FBOs can co-implement via funding, technical support, training curricula, etc. | 98 (97.0) | 3 (3.0) |

NGO = Non-Governmental Organization; CSO = Civil Society Organization; FBO = Faith-Based Organization

Table 3. Factors Associated with Knowledge Level on the Dissemination and Implementation of Doula Support Service (N = 101)

| Variable | Moderate n (%) | Good n (%) | Total n (%) | χ² (p-value) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

| Sex | 0.42 (0.518) | ||||

| Male | 1 (14.3) | 6 (85.7) | 7 (100.0) | 2.07 (0.22–19.71) | |

| Female | 7 (7.4) | 87 (92.6) | 94 (100.0) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Age (years) | 1.77 (0.184) | ||||

| ≤ 42 | 6 (11.3) | 47 (88.7) | 53 (100.0) | 2.94 (0.56–15.31) | |

| > 42 | 2 (4.2) | 46 (95.8) | 48 (100.0) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Educational level | 1.40 (0.237) | ||||

| Graduate | 8 (9.2) | 79 (90.8) | 87 (100.0) | 0.91 (0.85–0.97) | |

| Postgraduate | 0 (0.0) | 14 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Experience (years) | 4.03 (0.045)* | ||||

| ≤ 18 | 8 (11.6) | 61 (88.4) | 69 (100.0) | 1.13ᵃ (0.81–0.96) | |

| > 18 | 0 (0.0) | 32 (100.0) | 32 (100.0) | 1 [Reference] |

CI = Confidence Interval.

Discussion

The finding that all respondents correctly identify what doulas are and what they do indicates that basic knowledge and beliefs about the intervention (an individual-level construct in CFIR) are already strongly aligned. Rather than an “innovation nobody understands,” doula care is perceived as a legitimate, well-defined intervention that fits the local understanding of labour support.

This reduces the usual early implementation barrier of conceptual confusion and suggests that subsequent work can focus less on explaining the concept and more on clarifying roles, boundaries, and workflows.

The fact that respondents consistently recognized doulas as trained, non-clinical personnel who offer physical, emotional, and informational support across pregnancy, labour, and the puerperium suggests that “knowledge and beliefs about the intervention” (a key CFIR construct) are already very strong in this context [7].

From an implementation-science perspective, this widespread knowledge can be interpreted as a form of pre-implementation readiness: the intervention is seen as both advantageous (filling gaps in continuous, non-clinical support) and compatible with the existing maternity model, especially in contexts where midwives are overstretched.

Within CFIR, this strengthens the constructs of relative advantage and compatibility under intervention characteristics, and suggests that the main challenges will not be “what is a doula?” but rather “how do we embed doulas safely and sustainably into an already pressured system?”.

This is significant because global evidence shows that continuous support during labour, often delivered by doulas, is associated with better outcomes such as higher rates of spontaneous vaginal birth, shorter labours, reduced use of intrapartum analgesia, lower caesarean and instrumental birth rates, and more positive birth experiences[4].

Summaries of doula interventions likewise report improvements in maternal satisfaction, breastfeeding, and sometimes reductions in preterm birth and low birth weight, particularly among socially disadvantaged women[12].

In the Nigerian setting, where recent UN and WHO estimates suggest that the country accounts for roughly a quarter to almost a third of global maternal deaths, and where the 2018 NDHS still reports an MMR of around 512 deaths per 100,000 live births, an intervention perceived as both clearly defined and beneficial represents a strong starting point. In CFIR terms, stakeholders appear to view doula care as having a clear relative advantage over current practice and good compatibility with existing maternity services, especially given chronic midwife shortages and high case-loads in many Nigerian facilities.

However, the results also suggest that stakeholders conceptualize doulas mainly as “supportive extenders” of midwifery care rather than parallel or competing providers. This aligns with international discussions that emphasize integrating doulas into interdisciplinary teams rather than creating new silos [13,14]. The high knowledge scores among respondents can be seen less as superficial awareness and more as a sign of cognitive readiness for implementation, provided role boundaries are carefully negotiated.

Respondents’ near-unanimous support for community-embedded dissemination pathways such as health talks, community dialogues, local radio, markets, churches, and culturally tailored messages indicates a shared understanding that doula services must be socially and culturally grounded to be acceptable in Bayelsa.

This maps closely onto CFIR’s Outer setting constructs of patient needs and resources and cosmopolitanism (linkages with external organizations). Stakeholders clearly recognize that many women in Nigeria face barriers such as low health literacy, financial constraints, and geographical inaccessibility, which influence where and how they encounter information about new services [15, 16]. The respondents’ emphasis on local language, trusted community venues, and face-to-face dialogue mirrors WHO guidance that respectful intrapartum care must include effective, culturally appropriate communication and continuous emotional support [4, 17, 18].

Also, from a RE-AIM perspective, such preferences are highly relevant to Reach and Adoption. The RE-AIM framework emphasizes that public-health impact depends not just on effectiveness but also on the proportion and representativeness of people who are reached and of settings that adopt an intervention [19, 20]. By pointing to dissemination strategies that operate where women already live, trade, pray, and socialize, the respondents are implicitly specifying high-Reach channels that may also enhance equity, particularly important in Bayelsa’s riverine and hard-to-reach communities.

At the same time, because almost all strategies were endorsed, the data make it difficult to prioritize. Implementation science would typically recommend using RE-AIM not only to identify acceptable strategies, but also to rank them by feasibility and potential impact. For instance, community radio may have broad geographic reach but require external funds, whereas church-based talks may have deep relational reach but depend heavily on individual clergy champions. The overwhelmingly positive findings therefore indicate strong openness to community-engaged dissemination but limited discrimination about which strategies are most critical to start with under resource constraints.

From the findings, there is very strong support for policy integration, structured training, clear referral pathways, and the embedding of doulas into existing public-sector schemes (e.g., alongside community midwifery). These preferences align closely with CFIR’s depiction of the Outer setting as a domain that includes external policies and incentives and Inner setting constructs such as implementation climate, leadership engagement, and available resources [21, 22].

International experience suggests that formal policy recognition (through legislation, clinical guidelines or reimbursement schemes) is often a turning point for doula scale-up. In high-income settings, for instance, Medicaid coverage of doula services has become a key policy instrument to reduce maternal health inequities and institutionalize doulas as legitimate members of the maternity workforce [23-25].

In CFIR philologic, such policies reinforce external incentives and mandates, influence how organizations prioritize resources, and shape implementation climate at the facility level (e.g., whether managers see doulas as “nice to have” or “required”). [24, 26].

At the same time, the findings also indicate strong endorsement of midwife-led implementation, that is, the idea that midwives should be the principal clinical champions, supervisors, or coordinators of doula services within facilities. This resonates with CFIR’s Inner setting constructs, such as networks and communication, and readiness for implementation, where frontline clinical champions play a critical role in normalizing new practices.

Global evidence underscores that midwives are central to respectful maternity care and to enabling continuous support during labor. WHO’s intrapartum care model explicitly positions midwives as key providers of both clinical care and emotional support, often working alongside companions of choice [4]. In other LMIC contexts, initiatives integrating traditional birth attendants into formal systems have stressed the need for clear supervisory relationships with midwives or nurses to avoid unsafe practices or role conflict [27]. The findings are therefore consistent with international experience that doula or birth-companion programs function best when midwives lead day-to-day operational decisions, such as when to call a doula, how to coordinate tasks, and how to handle emergencies.

Crucially, the findings suggest that policy integration (outer setting) and midwife-led implementation (inner setting) are strongly endorsed but not yet fully aligned in terms of governance. CFIR emphasizes that successful implementation depends on alignment across domains: external policies need to be compatible with local workflows, cultures, and resource realities (21)]. However, two plausible scenarios emerge from findings: Policy without practice, such as even if state or national policies formally recognize doulas, implementation could remain superficial if midwives do not feel genuinely involved, supported, or protected. Studies of Medicaid doula benefit implementation in the US show that reimbursement policies alone are insufficient; organizational culture, workload, training, and inter-professional relationships significantly modulate actual uptake [23], and Practice without protection where midwives may be enthusiastic and begin informally collaborating with doulas but without policy backing, doula roles may lack legal clarity, funding, supervision structures and institutional sustainability. Similar tensions have been observed in efforts to integrate lay health workers and TBAs in LMICs: pilots may show promise, yet scaling is constrained without formal policies, job descriptions, and financing[27].

The respondents’ strong agreement on standardized training, referral pathways, and supervision can therefore be interpreted as a call for “bridging mechanisms” that connect outer-setting policy ambitions to inner-setting realities. In RE-AIM terms, these mechanisms are likely to shape Adoption (facility willingness to take up doula programs) and Implementation quality (fidelity, safety, and consistency).

One of the most analytically important findings in this study is the lack of clear consensus on who should lead doula implementation, beyond general agreement that midwives have a central role. Support for hospital management and community leaders as lead actors appears much more fragmented. In CFIR, leadership engagement and implementation climate are core determinants of whether an innovation is prioritized, resourced, and integrated into routine practice [21]. Research on large-scale maternal health initiatives shows that even when frontline staff are supportive, weak or ambiguous leadership can result in “islands of excellence” that fail to spread, or in pilots that collapse once external project funding ends [28].

The findings hint at competing leadership narratives: Some respondents implicitly favor a clinic-centric model, where midwives lead, managers provide minimal oversight, and communities act primarily as recipients or supporters. Others appear to expect hospital management to set the vision, allocate resources, and champion doula integration in strategic and budgetary for a. while few see community leaders as formal leads, possibly reflecting concerns about politicization or role conflicts, even though they strongly support community-based dissemination.

This ambiguity poses several risks such as diffuse accountability if everyone believes someone else is “in charge,” critical decisions about training curricula, supervision structures, remuneration, conflict resolution and data reporting may be delayed or neglected, role conflict and mistrust in contexts where obstetric violence and power asymmetries in maternity care have been documented (e.g., in Nigerian facilities) unclear leadership could exacerbate tensions between midwives, doctors, doulas and community actors, and implementation inequities where facilities with charismatic individual champions (e.g., a motivated matron or medical director) may progress quickly, while others stagnate, creating geographical inequities in access to doula support [12].

In the lens of implementation science, this would therefore interpret the leadership findings as a “warning light”: despite widespread enthusiasm for doula support, governance structures are not yet fully articulated. therefore steps, guided by CFIR and RE-AIM, would be to co-design a clear leadership and accountability model, such as (a) Policy-level leadership (Ministry/SMOH) for mandates and financing. (b) Organizational leadership (hospital/PHC management) for institutionalization and quality assurance. c) clinical leadership (midwives) for day-to-day implementation and (d) community leadership (traditional, religious, and women’s groups) for demand generation and social accountability.

Finally, this study revealed no significant association between age, gender, educational status, and work experience with knowledge of stakeholders on doula support services dissemination and implementation.

A probable explanation is that, in facility and regulatory contexts, “knowledge for implementation” is primarily shaped by organizational access-to-information pathways, formal training, guideline circulation, meetings, mentorship, and supervisory communication rather than by demographic attributes such as gender. This aligns with CFIR, which treats implementation-related knowledge as a function of inner setting readiness, learning climate, and access to knowledge and information, interacting with the “characteristics of individuals.”

Moreover, age often functions as a weak proxy for implementation knowledge because knowledge is more directly influenced by recent training, routine engagement with evidence, and access to knowledge infrastructure than by chronological age. CFIR again supports this: the mechanism is not age, but whether the organization enables learning and information access, and whether individuals are positioned to receive and use that information [7, 21].

A key explanation is that doula D&I knowledge is often practice- and system-specific, and may be acquired through workplace implementation exposure (policy discussions, program planning, SOP development, committee work, [21] inter-professional coordination) rather than from degree level alone. In CFIR terms, knowledge acquisition is enabled by access to knowledge and information, and the learning climate within the organizational conditions that can reduce the marginal effect of higher credentials [7, 21].

Implementation knowledge is commonly strengthened through cumulative exposure to real-world implementation processes such as policy translation, service integration, referral pathway design, stakeholder engagement, and continuous quality improvement activities. CFIR explicitly frames these as interacting influences across inner setting, individual characteristics, and the implementation process (planning, engaging, executing, reflecting/evaluating) [21, 29].

In combination, these strategies translate strong community buy-in into dependable, respectful, and safe service delivery. They also align with global guidance that implementation must be context-fitted, competency-based, and continuously improved.

However, the findings reveal an important methodological pattern. The data show overwhelmingly positive results across most items. While this demonstrates strong normative support for doula services, it creates a ceiling effect that limits what can be inferred. The pattern is also consistent with social desirability bias, well-recognized threats to validity in health research.

Furthermore, because almost all strategies and enabling factors receive near-universal endorsement, the survey is less able to tell which components are most critical or where respondents anticipate real trade-offs.

Implementation frameworks like RE-AIM and CFIR are powerful precisely because they help differentiate between high-priority determinants and nice-to-have features; however, the current results tend to show enthusiasm but not prioritization. This is a limitation of this study.

Conclusion

This quantitative appraisal demonstrates a strong strategic consensus among stakeholders in Bayelsa State for a multi-level framework to integrate doula support into the maternity care system. The endorsed package prioritizes formal policy backing, midwife-led clinical integration with defined roles and referral pathways, standardized local training emphasizing psychosocial support and basic risk recognition, culturally adapted community dissemination, and structured supervision.

Practically, this consensus provides a direct blueprint for action: (i) developing state-level doula guidelines, (ii) integrating doulas into existing community midwifery schemes with clear protocols, (iii) implementing a context-specific curriculum and certification, and (iv) launching tailored community outreach. Initial rollout should employ implementation-science indicators (e.g., reach, fidelity) and rapid learning cycles for adaptation.

While the study benefits from strong stakeholder alignment and a theory-informed design, its single-state scope, cross-sectional nature, and reliance on self-report limit generalizability and causal inference.

Future research should progress to mixed-methods pilot studies, employing Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles to test implementation feasibility and assess maternal and neonatal outcomes, equity impacts, and cost-effectiveness. Further qualitative inquiry is also needed to explore underlying tensions in leadership and sustainability not captured by this survey. If implemented with clear policy, prepared workforces, and community engagement, this stakeholder-informed model offers a viable pathway to institutionalize doula support as a person-centred complement to midwifery care, potentially improving the experience and outcomes of maternity services in Bayelsa State and similar contexts.

Ethics Consideration

This study received ethical approval from four relevant institutions in Bayelsa State, Nigeria: the Federal Medical Centre, Yenagoa (protocol number: 1018); the Niger Delta University Teaching Hospital, Okolobiri (NDUTH/REC/0060/2025); the Bayelsa State Ministry of Health (reference: BY/SMOH/HPRS/HP/VOL.1/2025); and the Bayelsa State Hospitals Management Board (reference: BSHMB/ADM/314/VOL.1/57). The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of respect for persons, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants after explaining the study's purpose, procedures, and their right to withdraw without consequence. Confidentiality and anonymity were maintained throughout the study, and all data were stored securely in compliance with the guidelines of the approving ethics committees

Acknowledgements

The researchers sincerely thanked all the respondents who participated in the study. Additionally, the authors also express gratitude for the support received from Federal Medical Centre Yenagoa, Niger Delta University Teaching Hospital, Okolobiri, Ministry of Health, Bayelsa State, and the Bayelsa State Hospitals’ Management Board.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study received funding from the Academic Staff :union: of Universities (ASUU).

Authors' Contributions

Jimmy Agada J: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing, Original Draft Preparation.

Wankasi Idubamo H: Conceptualization,

Supervision, Validation, Writing – Review &

Editing.

All authors read and approved the version for submission.

Artificial Intelligence Utilization

Artificial intelligence was used in correcting grammar and reference management.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The finding that all respondents correctly identify what doulas are and what they do indicates that basic knowledge and beliefs about the intervention (an individual-level construct in CFIR) are already strongly aligned. Rather than an “innovation nobody understands,” doula care is perceived as a legitimate, well-defined intervention that fits the local understanding of labour support.

This reduces the usual early implementation barrier of conceptual confusion and suggests that subsequent work can focus less on explaining the concept and more on clarifying roles, boundaries, and workflows.

The fact that respondents consistently recognized doulas as trained, non-clinical personnel who offer physical, emotional, and informational support across pregnancy, labour, and the puerperium suggests that “knowledge and beliefs about the intervention” (a key CFIR construct) are already very strong in this context [7].

From an implementation-science perspective, this widespread knowledge can be interpreted as a form of pre-implementation readiness: the intervention is seen as both advantageous (filling gaps in continuous, non-clinical support) and compatible with the existing maternity model, especially in contexts where midwives are overstretched.

Within CFIR, this strengthens the constructs of relative advantage and compatibility under intervention characteristics, and suggests that the main challenges will not be “what is a doula?” but rather “how do we embed doulas safely and sustainably into an already pressured system?”.

This is significant because global evidence shows that continuous support during labour, often delivered by doulas, is associated with better outcomes such as higher rates of spontaneous vaginal birth, shorter labours, reduced use of intrapartum analgesia, lower caesarean and instrumental birth rates, and more positive birth experiences[4].

Summaries of doula interventions likewise report improvements in maternal satisfaction, breastfeeding, and sometimes reductions in preterm birth and low birth weight, particularly among socially disadvantaged women[12].

In the Nigerian setting, where recent UN and WHO estimates suggest that the country accounts for roughly a quarter to almost a third of global maternal deaths, and where the 2018 NDHS still reports an MMR of around 512 deaths per 100,000 live births, an intervention perceived as both clearly defined and beneficial represents a strong starting point. In CFIR terms, stakeholders appear to view doula care as having a clear relative advantage over current practice and good compatibility with existing maternity services, especially given chronic midwife shortages and high case-loads in many Nigerian facilities.

However, the results also suggest that stakeholders conceptualize doulas mainly as “supportive extenders” of midwifery care rather than parallel or competing providers. This aligns with international discussions that emphasize integrating doulas into interdisciplinary teams rather than creating new silos [13,14]. The high knowledge scores among respondents can be seen less as superficial awareness and more as a sign of cognitive readiness for implementation, provided role boundaries are carefully negotiated.

Respondents’ near-unanimous support for community-embedded dissemination pathways such as health talks, community dialogues, local radio, markets, churches, and culturally tailored messages indicates a shared understanding that doula services must be socially and culturally grounded to be acceptable in Bayelsa.

This maps closely onto CFIR’s Outer setting constructs of patient needs and resources and cosmopolitanism (linkages with external organizations). Stakeholders clearly recognize that many women in Nigeria face barriers such as low health literacy, financial constraints, and geographical inaccessibility, which influence where and how they encounter information about new services [15, 16]. The respondents’ emphasis on local language, trusted community venues, and face-to-face dialogue mirrors WHO guidance that respectful intrapartum care must include effective, culturally appropriate communication and continuous emotional support [4, 17, 18].

Also, from a RE-AIM perspective, such preferences are highly relevant to Reach and Adoption. The RE-AIM framework emphasizes that public-health impact depends not just on effectiveness but also on the proportion and representativeness of people who are reached and of settings that adopt an intervention [19, 20]. By pointing to dissemination strategies that operate where women already live, trade, pray, and socialize, the respondents are implicitly specifying high-Reach channels that may also enhance equity, particularly important in Bayelsa’s riverine and hard-to-reach communities.

At the same time, because almost all strategies were endorsed, the data make it difficult to prioritize. Implementation science would typically recommend using RE-AIM not only to identify acceptable strategies, but also to rank them by feasibility and potential impact. For instance, community radio may have broad geographic reach but require external funds, whereas church-based talks may have deep relational reach but depend heavily on individual clergy champions. The overwhelmingly positive findings therefore indicate strong openness to community-engaged dissemination but limited discrimination about which strategies are most critical to start with under resource constraints.

From the findings, there is very strong support for policy integration, structured training, clear referral pathways, and the embedding of doulas into existing public-sector schemes (e.g., alongside community midwifery). These preferences align closely with CFIR’s depiction of the Outer setting as a domain that includes external policies and incentives and Inner setting constructs such as implementation climate, leadership engagement, and available resources [21, 22].

International experience suggests that formal policy recognition (through legislation, clinical guidelines or reimbursement schemes) is often a turning point for doula scale-up. In high-income settings, for instance, Medicaid coverage of doula services has become a key policy instrument to reduce maternal health inequities and institutionalize doulas as legitimate members of the maternity workforce [23-25].

In CFIR philologic, such policies reinforce external incentives and mandates, influence how organizations prioritize resources, and shape implementation climate at the facility level (e.g., whether managers see doulas as “nice to have” or “required”). [24, 26].

At the same time, the findings also indicate strong endorsement of midwife-led implementation, that is, the idea that midwives should be the principal clinical champions, supervisors, or coordinators of doula services within facilities. This resonates with CFIR’s Inner setting constructs, such as networks and communication, and readiness for implementation, where frontline clinical champions play a critical role in normalizing new practices.

Global evidence underscores that midwives are central to respectful maternity care and to enabling continuous support during labor. WHO’s intrapartum care model explicitly positions midwives as key providers of both clinical care and emotional support, often working alongside companions of choice [4]. In other LMIC contexts, initiatives integrating traditional birth attendants into formal systems have stressed the need for clear supervisory relationships with midwives or nurses to avoid unsafe practices or role conflict [27]. The findings are therefore consistent with international experience that doula or birth-companion programs function best when midwives lead day-to-day operational decisions, such as when to call a doula, how to coordinate tasks, and how to handle emergencies.

Crucially, the findings suggest that policy integration (outer setting) and midwife-led implementation (inner setting) are strongly endorsed but not yet fully aligned in terms of governance. CFIR emphasizes that successful implementation depends on alignment across domains: external policies need to be compatible with local workflows, cultures, and resource realities (21)]. However, two plausible scenarios emerge from findings: Policy without practice, such as even if state or national policies formally recognize doulas, implementation could remain superficial if midwives do not feel genuinely involved, supported, or protected. Studies of Medicaid doula benefit implementation in the US show that reimbursement policies alone are insufficient; organizational culture, workload, training, and inter-professional relationships significantly modulate actual uptake [23], and Practice without protection where midwives may be enthusiastic and begin informally collaborating with doulas but without policy backing, doula roles may lack legal clarity, funding, supervision structures and institutional sustainability. Similar tensions have been observed in efforts to integrate lay health workers and TBAs in LMICs: pilots may show promise, yet scaling is constrained without formal policies, job descriptions, and financing[27].

The respondents’ strong agreement on standardized training, referral pathways, and supervision can therefore be interpreted as a call for “bridging mechanisms” that connect outer-setting policy ambitions to inner-setting realities. In RE-AIM terms, these mechanisms are likely to shape Adoption (facility willingness to take up doula programs) and Implementation quality (fidelity, safety, and consistency).

One of the most analytically important findings in this study is the lack of clear consensus on who should lead doula implementation, beyond general agreement that midwives have a central role. Support for hospital management and community leaders as lead actors appears much more fragmented. In CFIR, leadership engagement and implementation climate are core determinants of whether an innovation is prioritized, resourced, and integrated into routine practice [21]. Research on large-scale maternal health initiatives shows that even when frontline staff are supportive, weak or ambiguous leadership can result in “islands of excellence” that fail to spread, or in pilots that collapse once external project funding ends [28].

The findings hint at competing leadership narratives: Some respondents implicitly favor a clinic-centric model, where midwives lead, managers provide minimal oversight, and communities act primarily as recipients or supporters. Others appear to expect hospital management to set the vision, allocate resources, and champion doula integration in strategic and budgetary for a. while few see community leaders as formal leads, possibly reflecting concerns about politicization or role conflicts, even though they strongly support community-based dissemination.

This ambiguity poses several risks such as diffuse accountability if everyone believes someone else is “in charge,” critical decisions about training curricula, supervision structures, remuneration, conflict resolution and data reporting may be delayed or neglected, role conflict and mistrust in contexts where obstetric violence and power asymmetries in maternity care have been documented (e.g., in Nigerian facilities) unclear leadership could exacerbate tensions between midwives, doctors, doulas and community actors, and implementation inequities where facilities with charismatic individual champions (e.g., a motivated matron or medical director) may progress quickly, while others stagnate, creating geographical inequities in access to doula support [12].

In the lens of implementation science, this would therefore interpret the leadership findings as a “warning light”: despite widespread enthusiasm for doula support, governance structures are not yet fully articulated. therefore steps, guided by CFIR and RE-AIM, would be to co-design a clear leadership and accountability model, such as (a) Policy-level leadership (Ministry/SMOH) for mandates and financing. (b) Organizational leadership (hospital/PHC management) for institutionalization and quality assurance. c) clinical leadership (midwives) for day-to-day implementation and (d) community leadership (traditional, religious, and women’s groups) for demand generation and social accountability.

Finally, this study revealed no significant association between age, gender, educational status, and work experience with knowledge of stakeholders on doula support services dissemination and implementation.

A probable explanation is that, in facility and regulatory contexts, “knowledge for implementation” is primarily shaped by organizational access-to-information pathways, formal training, guideline circulation, meetings, mentorship, and supervisory communication rather than by demographic attributes such as gender. This aligns with CFIR, which treats implementation-related knowledge as a function of inner setting readiness, learning climate, and access to knowledge and information, interacting with the “characteristics of individuals.”

Moreover, age often functions as a weak proxy for implementation knowledge because knowledge is more directly influenced by recent training, routine engagement with evidence, and access to knowledge infrastructure than by chronological age. CFIR again supports this: the mechanism is not age, but whether the organization enables learning and information access, and whether individuals are positioned to receive and use that information [7, 21].

A key explanation is that doula D&I knowledge is often practice- and system-specific, and may be acquired through workplace implementation exposure (policy discussions, program planning, SOP development, committee work, [21] inter-professional coordination) rather than from degree level alone. In CFIR terms, knowledge acquisition is enabled by access to knowledge and information, and the learning climate within the organizational conditions that can reduce the marginal effect of higher credentials [7, 21].

Implementation knowledge is commonly strengthened through cumulative exposure to real-world implementation processes such as policy translation, service integration, referral pathway design, stakeholder engagement, and continuous quality improvement activities. CFIR explicitly frames these as interacting influences across inner setting, individual characteristics, and the implementation process (planning, engaging, executing, reflecting/evaluating) [21, 29].

In combination, these strategies translate strong community buy-in into dependable, respectful, and safe service delivery. They also align with global guidance that implementation must be context-fitted, competency-based, and continuously improved.

However, the findings reveal an important methodological pattern. The data show overwhelmingly positive results across most items. While this demonstrates strong normative support for doula services, it creates a ceiling effect that limits what can be inferred. The pattern is also consistent with social desirability bias, well-recognized threats to validity in health research.

Furthermore, because almost all strategies and enabling factors receive near-universal endorsement, the survey is less able to tell which components are most critical or where respondents anticipate real trade-offs.

Implementation frameworks like RE-AIM and CFIR are powerful precisely because they help differentiate between high-priority determinants and nice-to-have features; however, the current results tend to show enthusiasm but not prioritization. This is a limitation of this study.

Conclusion

This quantitative appraisal demonstrates a strong strategic consensus among stakeholders in Bayelsa State for a multi-level framework to integrate doula support into the maternity care system. The endorsed package prioritizes formal policy backing, midwife-led clinical integration with defined roles and referral pathways, standardized local training emphasizing psychosocial support and basic risk recognition, culturally adapted community dissemination, and structured supervision.

Practically, this consensus provides a direct blueprint for action: (i) developing state-level doula guidelines, (ii) integrating doulas into existing community midwifery schemes with clear protocols, (iii) implementing a context-specific curriculum and certification, and (iv) launching tailored community outreach. Initial rollout should employ implementation-science indicators (e.g., reach, fidelity) and rapid learning cycles for adaptation.

While the study benefits from strong stakeholder alignment and a theory-informed design, its single-state scope, cross-sectional nature, and reliance on self-report limit generalizability and causal inference.