Preventive Care in Nursing and Midwifery Journal

Volume 15, Issue 1 (1-2025)

Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J 2025, 15(1): 30-36 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: 400.14.5.4/13.248/102.9/2024

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Nikentari L A, Kristianto H, Yuliatun L, Haedar A, Irawan P L T. Blood glucose and neurological status: Dual predictors of survival in diabetic emergencies. Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J 2025; 15 (1) :30-36

URL: http://nmcjournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-944-en.html

URL: http://nmcjournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-944-en.html

Lintang Arum Nikentari

, Heri Kristianto *

, Heri Kristianto *

, Laily Yuliatun

, Laily Yuliatun

, Ali Haedar

, Ali Haedar

, Paulus Lucky Tirma Irawan

, Paulus Lucky Tirma Irawan

, Heri Kristianto *

, Heri Kristianto *

, Laily Yuliatun

, Laily Yuliatun

, Ali Haedar

, Ali Haedar

, Paulus Lucky Tirma Irawan

, Paulus Lucky Tirma Irawan

Nursing Department, Faculty of Health Sciences, Brawijaya University, Malang, Indonesia , heri.kristianto@ub.ac.id

Keywords: Diabetic Ketoacidosis, Glasgow Coma Scale, Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic Syndrome, Blood Glucose, Emergency Care

Full-Text [PDF 1024 kb]

(745 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1115 Views)

Knowledge Translation Statement

Audience: Emergency Department managers, emergency nurses, and clinical policymakers.

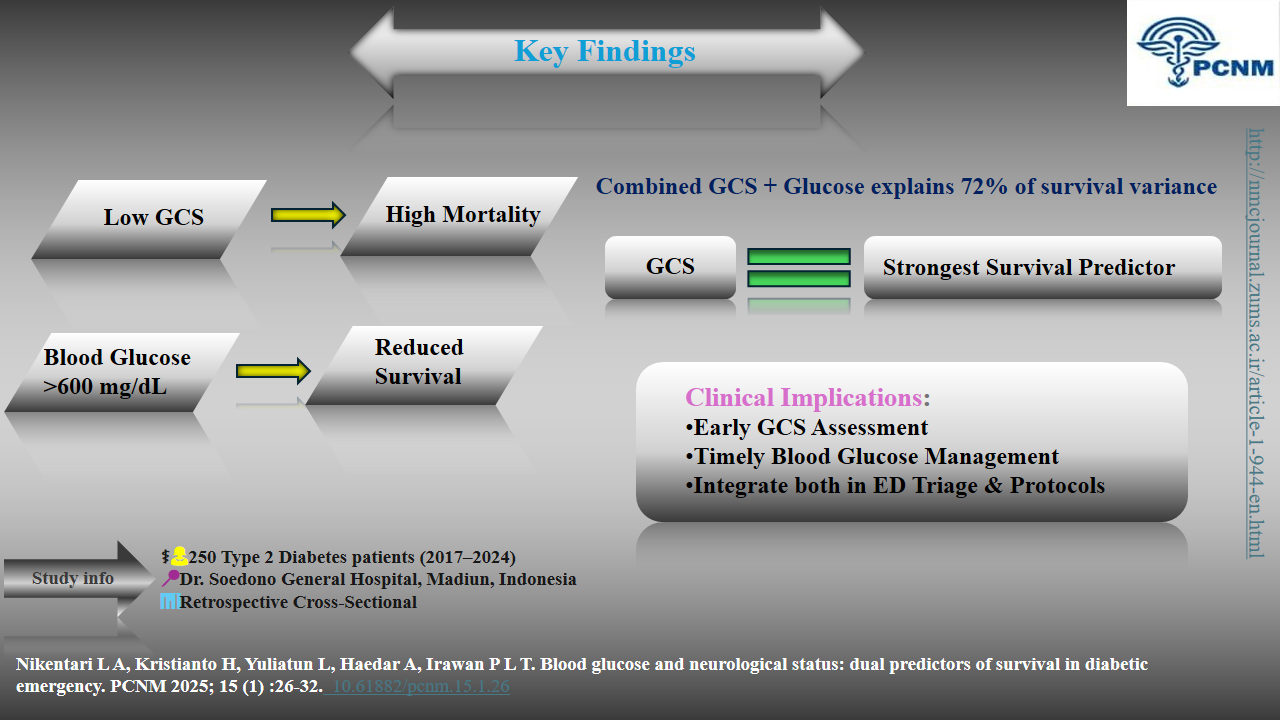

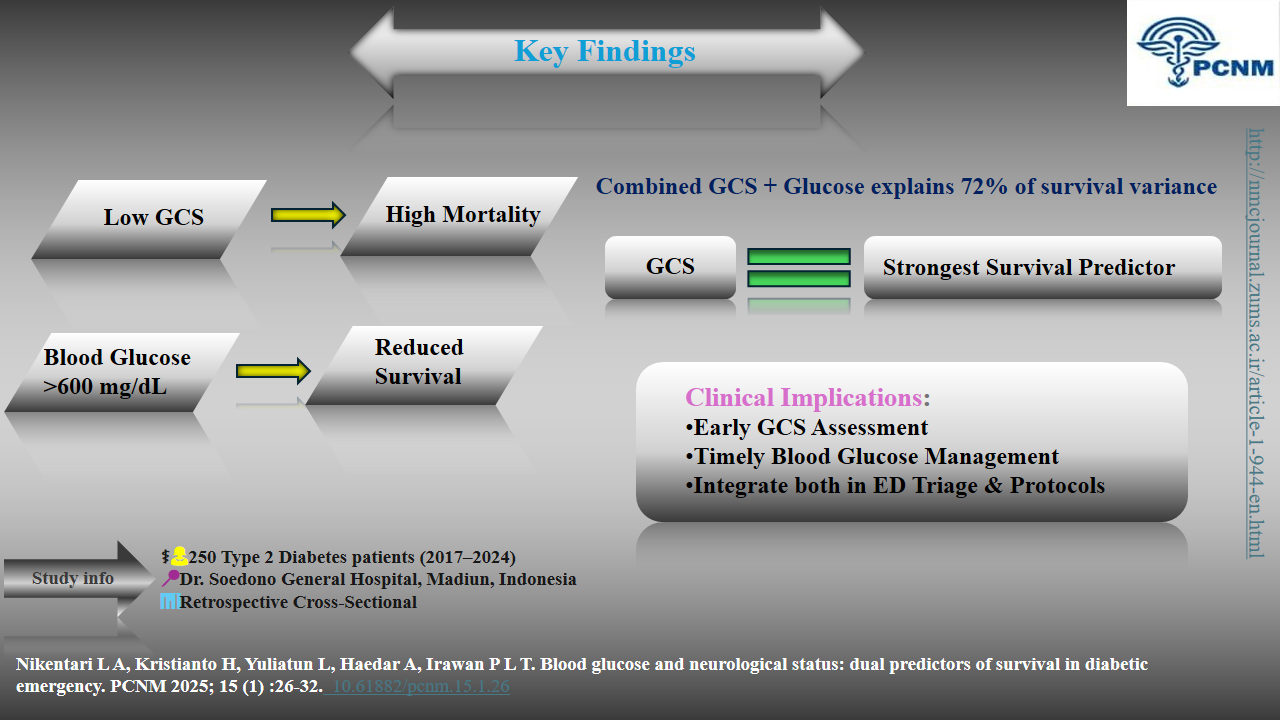

In diabetic emergencies, a low Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score is the strongest predictor of mortality, even more critical than extreme blood glucose levels. Triage protocols must prioritize immediate neurological assessment alongside glucose management to identify high-risk patients and guide life-saving interventions.

*p<0.05

Knowledge Translation Statement

Audience: Emergency Department managers, emergency nurses, and clinical policymakers.

In diabetic emergencies, a low Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score is the strongest predictor of mortality, even more critical than extreme blood glucose levels. Triage protocols must prioritize immediate neurological assessment alongside glucose management to identify high-risk patients and guide life-saving interventions.

Full-Text: (37 Views)

Introduction

Diabetic emergencies, including diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state (HHS), and hypoglycaemia, represent life-threatening conditions that require urgent medical intervention to prevent mortality and long-term complications [1].

These emergencies arise due to severe metabolic imbalances, which not only disrupt normal physiological functions but also significantly impact neurological status. Neurological dysfunction in diabetic emergencies often results from prolonged hyperglycaemia, cerebral edema, or hypoglycaemic-induced This study aims to investigate the dual predictive role of blood glucose levels and neurological status indetermining survival outcomes among diabetic emergency patients.neuronal damage, leading to altered levels of consciousness and increased morbidity [2]. Therefore, understanding the relationship between metabolic disturbances and neurological status is critical in improving patient outcomes. Previous studies have established a strong association between severe hyperglycaemia and poor clinical outcomes, with blood glucose levels exceeding 600 mg/dL being a significant predictor of mortality in diabetic emergencies [3]. Similarly, neurological impairment, as measured by GCS, has been shown to independently predict survival, with lower GCS scores correlating with an increased risk of death due to severe cerebral dysfunction and diminished recovery capacity [4]. The interplay between these two factors suggests that an integrated assessment of blood glucose levels and GCS can enhance prognostic accuracy and guide clinical decision-making in diabetic emergencies [5]. Despite advancements in emergency diabetes care, the prognostic role of combined metabolic and neurological assessments remains underexplored. While hyperglycaemia-induced metabolic stress exacerbates systemic complications, concomitant neurological deterioration may further reduce survival chances, necessitating an early and comprehensive evaluation of both parameters [6].

Objectives

This study aims to investigate the dual predictive role of blood glucose levels and neurological status in determining survival outcomes among diabetic emergency patients. By establishing the significance of these variables, the findings may contribute to the development of more refined clinical protocols and predictive models, ultimately improving emergency management strategies for diabetes-related complications.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This study employed a retrospective cross-sectional design. It was conducted at the Emergency Department (ED) of Dr. Soedono General Hospital, a Regional General Hospital (RSUD) in East Java, Indonesia. Data collection was carried out between July and September 2024.

Study Population and Sampling

The study population comprised medical records of patients aged over 30 years with a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus, who had been treated in the ED for hypoglycemia, hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS), or diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) over the preceding eight years (2017–2024).

Inclusion criteria were limited to patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus, selected through a time sampling method within this predefined period to ensure a representative dataset. This approach aimed to capture variations in patient characteristics, disease severity, and treatment outcomes while minimizing selection bias.

Exclusion criteria included patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes to maintain population homogeneity, as these conditions have distinct pathophysiologies and management strategies that could confound the analysis. Additionally, incomplete medical records were excluded to ensure data accuracy and reliability in assessing survival factors in diabetic emergency patients.

Sampling was performed using the time sampling method, resulting in a final sample of 250 patient medical records.

Data Collection

The medical records were retrieved from the hospital's electronic medical record database. The key variables extracted included:

Diabetic emergencies, including diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state (HHS), and hypoglycaemia, represent life-threatening conditions that require urgent medical intervention to prevent mortality and long-term complications [1].

These emergencies arise due to severe metabolic imbalances, which not only disrupt normal physiological functions but also significantly impact neurological status. Neurological dysfunction in diabetic emergencies often results from prolonged hyperglycaemia, cerebral edema, or hypoglycaemic-induced This study aims to investigate the dual predictive role of blood glucose levels and neurological status indetermining survival outcomes among diabetic emergency patients.neuronal damage, leading to altered levels of consciousness and increased morbidity [2]. Therefore, understanding the relationship between metabolic disturbances and neurological status is critical in improving patient outcomes. Previous studies have established a strong association between severe hyperglycaemia and poor clinical outcomes, with blood glucose levels exceeding 600 mg/dL being a significant predictor of mortality in diabetic emergencies [3]. Similarly, neurological impairment, as measured by GCS, has been shown to independently predict survival, with lower GCS scores correlating with an increased risk of death due to severe cerebral dysfunction and diminished recovery capacity [4]. The interplay between these two factors suggests that an integrated assessment of blood glucose levels and GCS can enhance prognostic accuracy and guide clinical decision-making in diabetic emergencies [5]. Despite advancements in emergency diabetes care, the prognostic role of combined metabolic and neurological assessments remains underexplored. While hyperglycaemia-induced metabolic stress exacerbates systemic complications, concomitant neurological deterioration may further reduce survival chances, necessitating an early and comprehensive evaluation of both parameters [6].

Objectives

This study aims to investigate the dual predictive role of blood glucose levels and neurological status in determining survival outcomes among diabetic emergency patients. By establishing the significance of these variables, the findings may contribute to the development of more refined clinical protocols and predictive models, ultimately improving emergency management strategies for diabetes-related complications.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This study employed a retrospective cross-sectional design. It was conducted at the Emergency Department (ED) of Dr. Soedono General Hospital, a Regional General Hospital (RSUD) in East Java, Indonesia. Data collection was carried out between July and September 2024.

Study Population and Sampling

The study population comprised medical records of patients aged over 30 years with a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus, who had been treated in the ED for hypoglycemia, hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS), or diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) over the preceding eight years (2017–2024).

Inclusion criteria were limited to patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus, selected through a time sampling method within this predefined period to ensure a representative dataset. This approach aimed to capture variations in patient characteristics, disease severity, and treatment outcomes while minimizing selection bias.

Exclusion criteria included patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes to maintain population homogeneity, as these conditions have distinct pathophysiologies and management strategies that could confound the analysis. Additionally, incomplete medical records were excluded to ensure data accuracy and reliability in assessing survival factors in diabetic emergency patients.

Sampling was performed using the time sampling method, resulting in a final sample of 250 patient medical records.

Data Collection

The medical records were retrieved from the hospital's electronic medical record database. The key variables extracted included:

- Demographic characteristics (age, gender)

- Blood glucose levels (mg/dL) at admission

- Neurological status assessed using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score

- Survival outcome (alive or deceased at discharge)

- Year of admission (from 2017 to 2024)

A trained medical records team was responsible for data entry and verification. Any records with incomplete or missing data for the key variables were excluded from the analysis.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Bivariate analysis was conducted using the chi-square test with a significance threshold of p < 0.25 to identify variables associated with survival. Multivariate analysis was then performed using binomial logistic regression with a significance level of p < 0.05 to determine the independent predictors of survival. The model's explanatory power was assessed using the R Square value.

Results

The trend in the incidence of diabetic emergency cases from 2017 to 2024 is illustrated in Figure 1, with data presented clearly to facilitate interpretation. Notable fluctuations in case numbers were observed across the years, which may correlate with advancements in diabetes management and changes in patient health status. In 2017 and 2018, the cases remained relatively stable at approximately 2.96% and 2.20%, respectively. However, a significant rise of 21.97% occurred in 2019, followed by a reduction in subsequent years, with cases dropping to 10.70% in 2020 and 8.40% in 2021. The decline in cases during this period may reflect improvements in diabetes management strategies. In 2022, a sharp decline to 2.29% was recorded, yet a dramatic increase was observed in 2023, reaching 35.82%. This surge may be linked to the escalating incidence of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state (HHS), possibly due to deteriorating patient health or delays in seeking treatment. By 2024, the percentage of cases fell to 15.66%, though it remained higher than in the early years of the study period, suggesting that challenges in diabetic emergency management persisted. Additionally, the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was identified as a significant predictor of survival, with low GCS scores strongly associated with mortality (OR = 0.002, 95% CI: 0.000–0.012, p < 0.05). Blood glucose levels >600 mg/dl were also linked to reduced survival rates (OR=0.113, 95% CI: 0.074–4.304, p<0.05). The model accounted for 72.1% of the variance in patient outcomes. Given its crucial role in patient prognosis, further analysis was conducted to assess potential confounding factors, such as comorbidities and treatment variability, which could influence survival outcomes. Detailed percentages for each year are provided in Figure 1.

The characteristics of patients experiencing diabetic emergencies from 2017 to 2024 are summarized in Table 1. The majority of patients were elderly (71.3 %) and predominantly male (69.3 %). Blood glucose levels varied widely, with a substantial proportion experiencing severe hypoglycemia or extreme hyperglycemia. Neurological status, assessed using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), showed a distribution across low, moderate, and high categories. In terms of survival, more than half of the patients survived, while a significant proportion did not. Further details on age distribution, gender, blood glucose levels, GCS scores, and survival rates are provided in Table 1.

Tabel 1. Characteristics, Blood Glucose Levels, and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) Scores of Diabetic Emergency Patients 2017–2024 (N=250)

Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Bivariate analysis was conducted using the chi-square test with a significance threshold of p < 0.25 to identify variables associated with survival. Multivariate analysis was then performed using binomial logistic regression with a significance level of p < 0.05 to determine the independent predictors of survival. The model's explanatory power was assessed using the R Square value.

Results

The trend in the incidence of diabetic emergency cases from 2017 to 2024 is illustrated in Figure 1, with data presented clearly to facilitate interpretation. Notable fluctuations in case numbers were observed across the years, which may correlate with advancements in diabetes management and changes in patient health status. In 2017 and 2018, the cases remained relatively stable at approximately 2.96% and 2.20%, respectively. However, a significant rise of 21.97% occurred in 2019, followed by a reduction in subsequent years, with cases dropping to 10.70% in 2020 and 8.40% in 2021. The decline in cases during this period may reflect improvements in diabetes management strategies. In 2022, a sharp decline to 2.29% was recorded, yet a dramatic increase was observed in 2023, reaching 35.82%. This surge may be linked to the escalating incidence of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state (HHS), possibly due to deteriorating patient health or delays in seeking treatment. By 2024, the percentage of cases fell to 15.66%, though it remained higher than in the early years of the study period, suggesting that challenges in diabetic emergency management persisted. Additionally, the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was identified as a significant predictor of survival, with low GCS scores strongly associated with mortality (OR = 0.002, 95% CI: 0.000–0.012, p < 0.05). Blood glucose levels >600 mg/dl were also linked to reduced survival rates (OR=0.113, 95% CI: 0.074–4.304, p<0.05). The model accounted for 72.1% of the variance in patient outcomes. Given its crucial role in patient prognosis, further analysis was conducted to assess potential confounding factors, such as comorbidities and treatment variability, which could influence survival outcomes. Detailed percentages for each year are provided in Figure 1.

The characteristics of patients experiencing diabetic emergencies from 2017 to 2024 are summarized in Table 1. The majority of patients were elderly (71.3 %) and predominantly male (69.3 %). Blood glucose levels varied widely, with a substantial proportion experiencing severe hypoglycemia or extreme hyperglycemia. Neurological status, assessed using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), showed a distribution across low, moderate, and high categories. In terms of survival, more than half of the patients survived, while a significant proportion did not. Further details on age distribution, gender, blood glucose levels, GCS scores, and survival rates are provided in Table 1.

Tabel 1. Characteristics, Blood Glucose Levels, and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) Scores of Diabetic Emergency Patients 2017–2024 (N=250)

| Characteristics | n = 250 | % | |

| Age | Adults (30 – 59 years) | 115 | 28.7 |

| Elderly (>60 years) | 135 | 71.3 | |

| Gender | Female | 123 | 30.7 |

| Male | 127 | 69.3 | |

| Blood Sugar Levels | <54 mg/dl | 161 | 64.4 |

| >250 mg/dl | 15 | 6.0 | |

| >600mg/dl | 74 | 29.6 | |

| GCS | Low (3 – 8) | 99 | 39.6 |

| Moderate (9 – 12) | 38 | 15.2 | |

| High (13 – 15) | 113 | 45.2 | |

| Survival Rate | Deceased | 91 | 36.4 |

| Alive | 159 | 63.6 | |

Tabel 2. Blood Glucose and Neurological Status in Survival Diabetic Emergency

| S.E. | df | p | R Square | Chi-Square (p <0.25) |

Multivariate (p <0.05) |

95% CI Exp (B) |

|

| Blood Sugar Levels | 0.028 | 0.073 | 0.113 | 0.002 (0.000–0.012) | |||

| <54 mg/dl | 0.528 | 2 | < 0.001 | ||||

| >250 mg/dl | 0.623 | 1 | < 0.001 | ||||

| >600mg/dl | 1.038 | 1 | 0.004 | ||||

| GCS | 0.721 | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | 0.113 (0.074–4.304) | |||

| Low | 0.842 | 2 | 0.113 | ||||

| Moderate | 0.840 | 1 | 0.098 | ||||

| High | 0.863 | 1 | 0.580 |

These findings highlight the critical role of neurological status in predicting survival outcomes among diabetic emergency patients. The strong association between low GCS scores and mortality suggests that impaired consciousness significantly increases the risk of poor prognosis (Table 2). This emphasizes the need for early neurological assessment in diabetic emergencies to guide clinical interventions. Although blood glucose levels were associated with survival in the bivariate analysis their significance diminished in the multivariate model, indicating that other factors, such as neurological status, play a more dominant role.

Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that neurological status, as assessed by the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), serves as the primary predictor of survival in patients experiencing diabetic emergencies. This is consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated a strong correlation between GCS scores and patient outcomes in acute metabolic conditions [7,4,8]. Additionally, blood glucose levels play a significant role, particularly when exceeding 600 mg/dL, which has been previously linked to increased mortality in hyperglycaemic crises. These findings emphasize the critical importance of prompt and continuous neurological assessment in the management of patients within the emergency department (ED) [9,10]. Patients exhibiting low GCS scores face an exceptionally high risk of mortality, aligning with previous research that identifies severe neurological impairment as a key determinant of adverse outcomes in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state (HHS)[10,11]. This underscores the need for early intervention strategies aimed at stabilizing the patient’s neurological condition to improve survival rates [12,13]. Moreover, both extreme hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia necessitate particularly careful attention [14]. Severe hyperglycaemia (above 600 mg/dL) has been strongly associated with a heightened risk of mortality, while hypoglycaemia (below 54 mg/dL) also presents substantial potential for serious complications, corroborating earlier studies that emphasize the dangers of extreme blood glucose fluctuations [15,16]. Consequently, close monitoring of blood glucose levels from the point of initial triage in the ED is essential to enhancing patient survival. These findings carry significant implications for the formulation of more comprehensive ED protocols, which should incorporate a combined evaluation of blood glucose levels and neurological status as a key component of the early triage process for diabetic emergency patients [17,18]. By adopting this approach, healthcare providers can allocate resources more effectively to those patients at the greatest risk, thereby improving clinical outcomes [19,20]. From a preventive standpoint, public health education plays a pivotal role in reducing the incidence of diabetic emergencies. This initiative involves educating patients and their families on effective home blood glucose management, early identification of complications such as DKA or HHS, and reinforcing the significance of regular health check-ups [21]. Community-based preventive programs that encourage healthy lifestyles, including balanced diets and regular physical activity, also play a crucial role in preventing acute complications [22]. This study provides valuable insights into the critical role of GCS in predicting survival in diabetic emergencies, reinforcing its importance in clinical decision-making. The integration of blood glucose levels as an additional predictor further enhances the study’s applicability to emergency care settings. However, there are limitations to consider. As a retrospective study conducted at a single institution, the findings may not be generalizable to other settings or populations. Additionally, the lack of longitudinal data prevents an assessment of long-term outcomes post-emergency treatment. Furthermore, while GCS and blood glucose levels are highlighted, other potential confounding factors influencing survival rates, such as comorbidities and treatment variations, warrant further investigation. Future research should be conducted with a larger population and a broader range of care conditions to validate these findings and aid in the development of risk prediction algorithms. By doing so, these results not only offer fresh insights into the management of diabetic emergencies but also provide a foundation for the creation of more effective preventive measures, ultimately enhancing the quality of life for diabetic patients.

Conclusion

This study highlights the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) as the primary predictor of survival in diabetic emergencies, with blood glucose levels also playing a significant role. Patients with low GCS scores are at an exceptionally high risk of mortality, emphasizing the importance of early neurological assessment and intervention in emergency care. The integration of both GCS and blood glucose levels in triage protocols can enhance patient outcomes by facilitating timely and appropriate medical interventions. Additionally, public health education on blood glucose management and early recognition of complications is essential in reducing the incidence of diabetic emergencies. Future studies should expand on these findings by incorporating larger sample sizes and exploring long-term patient outcomes to develop more precise risk prediction models.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Dr. Soedono General Hospital, Madiun (No. 400.14.5.4/23377/102.9/2024). As a retrospective analysis of anonymized medical records, informed consent was waived. All data were handled confidentially, with patient identifiers removed to ensure privacy.

Acknowledgments

The researchers extend their gratitude to Dr. Soedono General Hospital in Madiun for the support and permission to conduct this study. Appreciation is also given to all medical staff and personnel who contributed to data collection and provided valuable information. It is hoped that the results of this study can benefit the improvement of healthcare services at this hospital.

Conflict of Interest

The authors hereby declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors proudly acknowledge the funding for this research, authorship, and/or publication of this article under the 2024 Non-Head Lecturer Doctoral Grant Scheme, grant number 10993.1/UN10.F17/PT.01.03/2024, provided by Universitas Brawijaya.

Authors' Contributions

Nikentari L.A. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, data collection, and manuscript writing. Kristianto H. supervised the study, performed data analysis, reviewed the manuscript, and handled correspondence. Yuliatun L. conducted literature review, statistical analysis, manuscript editing, data interpretation, validation, and final approval. Haedar A. and Irawan P.L.T. provided administrative and technical support. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Artificial Intelligence Utilization

The authors declare that no generative AI technologies were used in the creation of this manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that neurological status, as assessed by the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), serves as the primary predictor of survival in patients experiencing diabetic emergencies. This is consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated a strong correlation between GCS scores and patient outcomes in acute metabolic conditions [7,4,8]. Additionally, blood glucose levels play a significant role, particularly when exceeding 600 mg/dL, which has been previously linked to increased mortality in hyperglycaemic crises. These findings emphasize the critical importance of prompt and continuous neurological assessment in the management of patients within the emergency department (ED) [9,10]. Patients exhibiting low GCS scores face an exceptionally high risk of mortality, aligning with previous research that identifies severe neurological impairment as a key determinant of adverse outcomes in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state (HHS)[10,11]. This underscores the need for early intervention strategies aimed at stabilizing the patient’s neurological condition to improve survival rates [12,13]. Moreover, both extreme hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia necessitate particularly careful attention [14]. Severe hyperglycaemia (above 600 mg/dL) has been strongly associated with a heightened risk of mortality, while hypoglycaemia (below 54 mg/dL) also presents substantial potential for serious complications, corroborating earlier studies that emphasize the dangers of extreme blood glucose fluctuations [15,16]. Consequently, close monitoring of blood glucose levels from the point of initial triage in the ED is essential to enhancing patient survival. These findings carry significant implications for the formulation of more comprehensive ED protocols, which should incorporate a combined evaluation of blood glucose levels and neurological status as a key component of the early triage process for diabetic emergency patients [17,18]. By adopting this approach, healthcare providers can allocate resources more effectively to those patients at the greatest risk, thereby improving clinical outcomes [19,20]. From a preventive standpoint, public health education plays a pivotal role in reducing the incidence of diabetic emergencies. This initiative involves educating patients and their families on effective home blood glucose management, early identification of complications such as DKA or HHS, and reinforcing the significance of regular health check-ups [21]. Community-based preventive programs that encourage healthy lifestyles, including balanced diets and regular physical activity, also play a crucial role in preventing acute complications [22]. This study provides valuable insights into the critical role of GCS in predicting survival in diabetic emergencies, reinforcing its importance in clinical decision-making. The integration of blood glucose levels as an additional predictor further enhances the study’s applicability to emergency care settings. However, there are limitations to consider. As a retrospective study conducted at a single institution, the findings may not be generalizable to other settings or populations. Additionally, the lack of longitudinal data prevents an assessment of long-term outcomes post-emergency treatment. Furthermore, while GCS and blood glucose levels are highlighted, other potential confounding factors influencing survival rates, such as comorbidities and treatment variations, warrant further investigation. Future research should be conducted with a larger population and a broader range of care conditions to validate these findings and aid in the development of risk prediction algorithms. By doing so, these results not only offer fresh insights into the management of diabetic emergencies but also provide a foundation for the creation of more effective preventive measures, ultimately enhancing the quality of life for diabetic patients.

Conclusion

This study highlights the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) as the primary predictor of survival in diabetic emergencies, with blood glucose levels also playing a significant role. Patients with low GCS scores are at an exceptionally high risk of mortality, emphasizing the importance of early neurological assessment and intervention in emergency care. The integration of both GCS and blood glucose levels in triage protocols can enhance patient outcomes by facilitating timely and appropriate medical interventions. Additionally, public health education on blood glucose management and early recognition of complications is essential in reducing the incidence of diabetic emergencies. Future studies should expand on these findings by incorporating larger sample sizes and exploring long-term patient outcomes to develop more precise risk prediction models.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Dr. Soedono General Hospital, Madiun (No. 400.14.5.4/23377/102.9/2024). As a retrospective analysis of anonymized medical records, informed consent was waived. All data were handled confidentially, with patient identifiers removed to ensure privacy.

Acknowledgments

The researchers extend their gratitude to Dr. Soedono General Hospital in Madiun for the support and permission to conduct this study. Appreciation is also given to all medical staff and personnel who contributed to data collection and provided valuable information. It is hoped that the results of this study can benefit the improvement of healthcare services at this hospital.

Conflict of Interest

The authors hereby declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors proudly acknowledge the funding for this research, authorship, and/or publication of this article under the 2024 Non-Head Lecturer Doctoral Grant Scheme, grant number 10993.1/UN10.F17/PT.01.03/2024, provided by Universitas Brawijaya.

Authors' Contributions

Nikentari L.A. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, data collection, and manuscript writing. Kristianto H. supervised the study, performed data analysis, reviewed the manuscript, and handled correspondence. Yuliatun L. conducted literature review, statistical analysis, manuscript editing, data interpretation, validation, and final approval. Haedar A. and Irawan P.L.T. provided administrative and technical support. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Artificial Intelligence Utilization

The authors declare that no generative AI technologies were used in the creation of this manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Type of Study: Orginal research |

Subject:

Nursing

References

1. Saifullah H. Diabetic emergency: diabetic ketoacidosis, hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state, euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis and hypoglycemia. International Journal of Contemporary Research. 2024;3(1):31-37. [https://multiarticlesjournal.com/counter/d/3-1-7/IJCRM-2024-3-1-7.pdf.]

2. Rusdi MS. Hipoglikemia pada pasien diabetes melitus. Journal Syifa Science and Clinical Research. 2020;2(September):83-90. [https://doi.org/10.37311/jsscr.v2i2.4575]

3. Muneer M, Akbar I. Acute metabolic emergencies in diabetes: DKA, HHS and EDKA. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2021;1307:85-114. [https://doi.org/10.1007/5584_2020_545] [PMID]

4. Lotter N, Lahri S, van Hoving DJ. The burden of diabetic emergencies on the resuscitation area of a district-level public hospital in Cape Town. African Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2021;11(4):416-421. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2021.05.004] [PMID]

5. Braine ME, Cook N. The Glasgow coma scale and evidence-informed practice: a critical review of where we are and where we need to be. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2017;26(1-2):280-293. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2021.05.004] [PMID]

6. Pawils S, Heumann S, Schneider SA, Metzner F, Mays D. The current state of international research on the effectiveness of school nurses in promoting the health of children and adolescents: an overview of reviews. PLOS One. 2023;18(4). [https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275724] [PMID]

7. Sarang B, Bhandarkar P, Raykar N, O'Reilly GM, Soni KD, Wärnberg MG, et al. Associations of on-arrival vital signs with 24-hour in-hospital mortality in adult trauma patients admitted to four public university hospitals in urban India: a prospective multi-centre cohort study. Injury. 2021;52(5):1158-1163. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2021.02.075] [PMID]

8. Akram Z, Inayat M, Akhtar S, Perveen R, Saeed R, Abid J, et al. Fasting influence on diabetic emergency visits in a tertiary care hospital throughout Ramadan and other lunar months. Pakistan Journal of Medical and Health Sciences. 2023;17(3):588-590. [https://doi.org/10.53350/pjmhs2023173588]

9. Maharjan J, Pandit S, Johansson KA, Khanal P, Karmacharya B, Kaur G, et al. Effectiveness of interventions for emergency care of hypoglycaemia and diabetic ketoacidosis: a systematic review. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2024;207. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2023.111078] [PMID]

10. Tamzil R, Yaacob N, Noor N, Baharuddin K. Comparing the clinical effects of balanced electrolyte solutions versus normal saline in managing diabetic ketoacidosis: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Turkish Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2023;23(3):131-138. [https://doi.org/10.4103/tjem.tjem_355_22] [PMID]

11. Blank SP, Blank RM, Ziegenfuss MD. The importance of hyperosmolarity in diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetic Medicine. 2020;37(12):2001-2008. [https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.14277] [PMID]

12. Watta R, Masi G, Katuuk ME. Screening faktor resiko diabetes melitus pada individu dengan riwayat keluarga diabetes melitus di RSUD Jailolo. Jurnal Keperawatan. 2020;8(1):44. [https://doi.org/10.35790/jkp.v8i1.28410]

13. Chen J, Zeng H, Ouyang X, Zhu M, Huang Q, Yu W, et al. The incidence, risk factors, and long-term outcomes of acute kidney injury in hospitalized diabetic ketoacidosis patients. BMC Nephrology. 2020;21(1):1-9. [https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-7-1] [PMID]

14. Banday MZ, Sameer AS, Nissar S. Pathophysiology of diabetes: an overview. Avicenna Journal of Medicine. 2020;10(4):174-188. [https://doi.org/10.4103/ajm.ajm_53_20] [PMID]

15. Gelaw NB, Muche AA, Alem AZ, Gebi NB, Chekol YM, Tesfie TK, et al. Development and validation of risk prediction model for diabetic neuropathy among diabetes mellitus patients at selected referral hospitals, in Amhara regional state Northwest Ethiopia, 2005-2021. PLOS One. 2023;18(8):e0276472. [https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276472] [PMID]

16. Wu XY, She DM, Wang F, Guo G, Li R, Fang P, et al. Clinical profiles, outcomes and risk factors among type 2 diabetic inpatients with diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state: a hospital-based analysis over a 6-year period. BMC Endocrine Disorders. 2020;20(1):1-9. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-020-00659-5] [PMID]

17. Katuuk ME, Sitorus R, Sukmarini L. Penerapan teori self care Orem dalam asuhan keperawatan pasien diabetes melitus. Jurnal Keperawatan. 2020;8(1):1-22. [https://doi.org/10.35790/jkp.v8i1.28405]

18. Barski L, Golbets E, Jotkowitz A, Schwarzfuchs D. Management of diabetic ketoacidosis. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2023;117:38-44. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2023.07.005] [PMID]

19. Jitraknatee J, Ruengorn C, Nochaiwong S. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic kidney disease among type 2 diabetes patients: a cross-sectional study in primary care practice. Scientific Reports. 2020;10(1):1-10. [https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63443-4] [PMID]

20. Dhatariya KK. The management of diabetic ketoacidosis in adults-an updated guideline from the Joint British Diabetes Society for Inpatient Care. Diabetic Medicine. 2022;39(6):e14788. [https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.14788] [PMID]

21. Wu F, Wu C, Wu Q, Yan F, Xiao Y, Du C. Prediction of death in intracerebral hemorrhage patients after minimally invasive surgery by vital signs and blood glucose. World Neurosurgery. 2024;184:e84-e94. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2024.01.061] [PMID]

22. Mohajan D, Mohajan HK. Hypoglycaemia among diabetes patients: a preventive approach. Journal of Innovative Medical Research. 2023;2(9):29-35. [https://doi.org/10.56397/JIMR/2023.09.05]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |