Preventive Care in Nursing and Midwifery Journal

Volume 15, Issue 3 (10-2025)

Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J 2025, 15(3): 50-60 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.SSU.REC.1398.070.

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Hosseini S E, setavand M, javadi M. Explaining the competencies required for intensive care unit nurses: A delphi study. Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J 2025; 15 (3) :50-60

URL: http://nmcjournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-972-en.html

URL: http://nmcjournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-972-en.html

Assistant professor, Department of Medical- Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing & Midwifery, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran , esmat.hosseini_110@yahoo.com

Full-Text [PDF 758 kb]

(119 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (335 Views)

The average age of the study subjects was 43.73 (13.23) years, with a total work experience of 17.1 (8.42) years (ICU work experience: 10.67 (4.98)). Weekly work hours were 49 (43.5-62.5). The most significant number of participants belonged to the group of nurses with a bachelor's degree, and the smallest to the group of intensive care fellows. The demographic characteristics of the populations are presented in Table 2.

At the stage of developing the questionnaire, items introduced by the interviewees as competencies or skills were coded. After merging similar codes, a total of 80 items were extracted. 24 articles and 5 theses that were most relevant to the topic were selected in the systematic review stage, and a total of 198 items were extracted.

After re-evaluating the 278 items obtained from the two systematic and interview stages, 71 items were removed due to overlap and repetition. A final questionnaire comprising 207 items was then formed (supplementary data). A content analysis of existing nursing role descriptions was conducted to identify the competencies required by intensive care unit nurses, yielding 17 competency domains (Table 3).

Table 2. Demographic Characteristics of the Delphi Panel Experts (N = 32)

Table 3. Competency Categories for Nurses Working in Intensive Care Units, with Example Items and Ratings

Knowledge Translation Statement

Audience: ICU nurse managers, hospital nursing directors, clinical nurse educators, and policymakers in critical care

A Delphi study establishes that ICU nurse competency is a multi-dimensional construct requiring both advanced technical skills and essential non-technical skills in ethics, communication, and family care. To ensure a proficient workforce, healthcare institutions must develop and implement standardized, evidence-based competency frameworks that move beyond task-checklists to holistically assess and train nurses in this full spectrum of skills.

Audience: ICU nurse managers, hospital nursing directors, clinical nurse educators, and policymakers in critical care

A Delphi study establishes that ICU nurse competency is a multi-dimensional construct requiring both advanced technical skills and essential non-technical skills in ethics, communication, and family care. To ensure a proficient workforce, healthcare institutions must develop and implement standardized, evidence-based competency frameworks that move beyond task-checklists to holistically assess and train nurses in this full spectrum of skills.

Full-Text: (122 Views)

Introduction

The nursing profession within a country's healthcare system is critically important, as nurses are at the forefront of delivering healthcare services. One of the most essential parts of the hospital, where specialized nursing services hold particular importance, is the intensive care unit (ICU) [1]. Intensive care is founded on continuous monitoring, the preservation of vital body functions, and the continuity of care; therefore, nursing care in the ICU is highly specialized in nature [1,2]. Nurses working in intensive care units must possess the appropriate knowledge, skills, experience, and qualifications to adequately assess and respond to the complex needs of critically ill patients [3].

Since hospitalized patients have very complex clinical conditions, all aspects of care and treatment are addressed in a more detailed and specialized manner [4]. Thus, nursing care in these settings must be accompanied by professional competencies, which include the judicious and consistent application of technical and communication skills, clinical knowledge and reasoning, emotions, and values in clinical environments [5]. Furthermore, evaluating these competencies is essential to ensure adherence to minimum professional standards and readiness to fulfill the role effectively. The development of nurses' competencies is, in essence, an investment in ensuring the safety, quality, and efficiency of patient care [6]. The term "competence" is a complex concept in nursing, and various professional and academic institutions have provided different definitions and classifications regarding it. For instance, Sheribante (1996) identified three main categories of competence: professional competence, cognitive competence, and interpersonal skills [6]. The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) emphasizes eight competencies: clinical judgment, ethical advocacy, caring practices, collaboration, systems thinking, responsiveness to diversity, clinical curiosity, creativity, assessment, and facilitation of learning [7,8].

Two groups of individual factors, such as knowledge and skills, adherence to ethical and professional standards, respect for oneself and others, work experience, effective communication, interest in the profession, responsibility and accountability, and organizational factors, such as clinical and educational environment, retraining programs, control and supervision, and an efficient educational system, are effective in the process of nurses acquiring clinical competence [9]. Research has shown that one of the significant factors influencing clinical competence is work experience [10,11].

Another critical point is that the field of nursing is constantly evolving and growing. Based on the information obtained from the types of competencies and their respective priorities, educational program objectives are identified, and necessary actions are taken to develop appropriate curricula [12,13]. This includes determining the type and amount of resources needed to achieve these objectives and planning for suitable training [14].

A recent scoping review reveals significant variation in the use of competencies and the level of performance expected of intensive care nurses [15]. Recent syntheses demonstrate substantial heterogeneity in how competencies for intensive care nursing are defined, operationalised, and assessed across settings, undermining international consensus on expected performance levels for ICU nurses. Consequently, several national and local initiatives have sought to develop context-specific competency frameworks [16].

The increasing acuity and complexity of critically ill patients, together with advances in personalised, technology-driven care, further necessitate the delineation of advanced nursing competencies to support autonomous clinical decision-making in the ICU [17]. Importantly, translating internationally derived competency frameworks into local practice requires attention to country-specific constraints. In Iran, national surveys and qualitative studies report the following: (a) regulatory constraints: lack of a unified and nationally approved set of critical care nursing standards; (b) educational constraints: limited access to formal competency-based training programs at higher levels for critical care nurses; and (c) diversity of resources and work environment: heterogeneity in equipment, staffing levels, and workload across institutions, all of which may hinder implementation [18].

Objectives

This Delphi study was conducted to develop an expert-validated and context-sensitive competency framework for ICU nurses.

Methods

We conducted a three-round Delphi study to identify and explain the competencies required for intensive care unit (ICU) nurses. The Delphi method is a systematic and iterative technique used to achieve consensus among subject matter experts through a series of questionnaires and controlled feedback rounds (REF) [19]. To ensure transparency and methodological rigor, the study followed the CREDES guideline for the conduct and reporting of Delphi studies (REF) [20].

To allow critical appraisal of the methodology and the recommendations generated, our research adhered to CREDES, a guideline for the conduct and reporting of Delphi studies [20].

This study was conducted between January 2020 and December 2021.

The selection of 32 panel members was based on methodological recommendations for Delphi studies, which emphasize that an expert panel typically ranges from 8 to 50 participants, depending on the study scope and heterogeneity of expertise [21]. In Delphi research, the inclusion of a heterogeneous group of experts is essential to capture a wide range of perspectives, generate high-quality responses, and achieve a reliable consensus [22].

Considering the multidimensional nature of intensive care nursing and the aim to ensure representation of clinical, managerial, and educational viewpoints, a purposive sampling strategy with maximum variation was employed. The number of panel members exceeded the minimum requirement to compensate for potential attrition between Delphi rounds, which is a recognized limitation of electronic Delphi designs [22].

Participants

Considering the multidisciplinary nature of ICU care and the need for heterogeneity, 32 experts were purposively selected to ensure representation of clinical, managerial, and educational perspectives. The panel included: two intensive care fellowship physicians, three nursing faculty members, three head nurses, eight master 's-level ICU nurses, eleven bachelor-level ICU nurses, and five postgraduate ICU nursing students (third semester and above). Inclusion criteria were: a minimum of five years of continuous ICU experience, current employment in adult general ICUs, and willingness to participate through all rounds. Nurses working primarily in neonatal or pediatric ICUs were excluded.

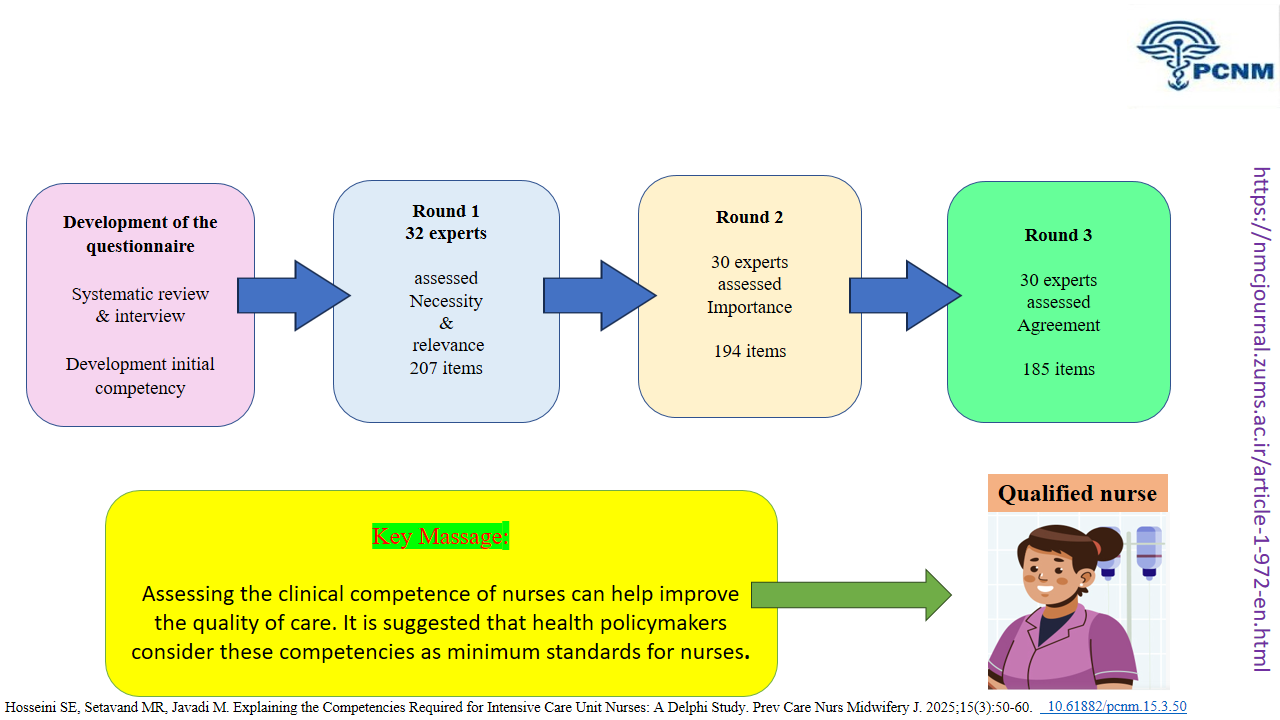

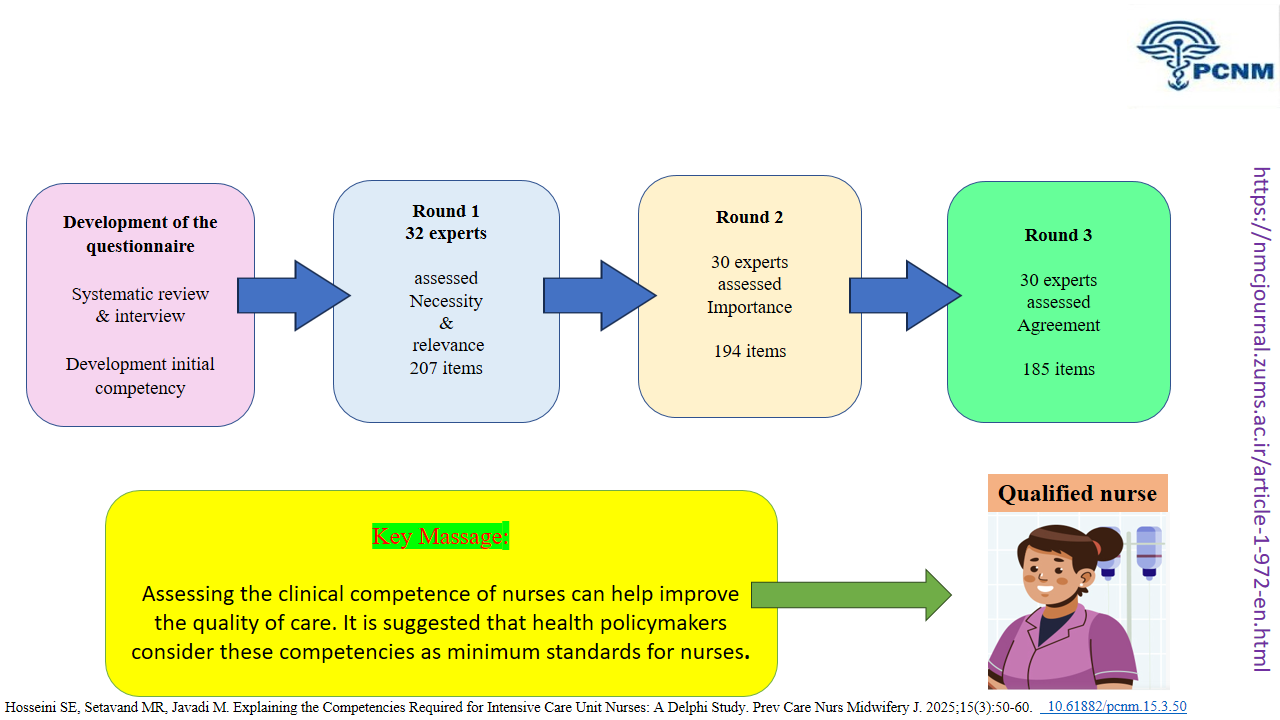

This study was conducted in four stages: Development of the questionnaire (qualitative interviews and systematic review), first round (presentation of the questionnaire formed in the preliminary stage, scoring the "necessity" and "relevance" of the items), second round (presentation of the results of the first round, presentation of the questionnaire for scoring the "importance" of the items), and third round (presentation of the results of the second round, presentation of the questionnaire in terms of "agreement" of the items)

Development of the questionnaire

This stage included qualitative interviews and systematic reviews. Interviews were conducted with three nurses and two head nurses who had a master's degree in critical care nursing and were working in the critical care unit.

Data were collected through in-depth, semi-structured individual interviews using a conventional content analysis approach as described by Hsieh and Shannon [23]. This approach was chosen because it allows categories and themes to emerge inductively from the data without imposing preconceived frameworks. Interviews were conducted by the first author, who was trained in qualitative research, in a quiet room within the ICU to ensure participants’ comfort and confidentiality. Each interview lasted between 40 and 70 minutes, depending on the participant’s willingness to elaborate on their experiences.

The interview guide included open-ended questions such as, “What competencies do you consider essential for nurses working in the ICU?” and “How do you demonstrate professional competence in critical situations?” Follow-up probes were used to encourage clarification and elaboration. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim immediately after each session, and reviewed for accuracy against the recordings.

Data analysis began simultaneously with data collection. Transcripts were read several times to achieve immersion in the data. Meaning units were identified, condensed, and labeled with codes, which were then grouped into subcategories and categories based on similarities and differences. Coding and categorization were performed manually and verified by two independent researchers to enhance analytic rigor.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted to identify studies published between January 1990 to September 2020. English databases, including SCOPUS, PubMed, OVID, ScienceDirect, ProQuest, and Persian databases such as Magiran and Google Scholar for grey literature. The following keywords were used: (“competency” OR “competencies” OR “clinical competence” OR “core competencies”) AND (“nurse*” OR “intensive care nurse*”) AND (“ICU” OR “intensive care unit”) AND (“professionalism” OR “clinical performance” OR “Professional Behavior” OR “criteria” OR “Professional Behavior”). Boolean operators AND and OR were used to combine the keywords.Data Integration and Saturation Criteria

To ensure methodological rigor, data saturation and integration procedures were carefully defined. Data saturation was achieved when no new competencies or themes emerged from the final two interviews, indicating that the qualitative data had sufficient depth and comprehensiveness.

To integrate the results of the qualitative phase with findings from the systematic review, all extracted competencies and skill items were organized in a unified comparison matrix. The research team independently reviewed and coded overlapping or conceptually similar items through iterative discussions until complete consensus was reached. This process ensured that both empirically derived competencies from the literature and contextually grounded insights from expert interviews were merged into a single, comprehensive competency framework. The integrated list of competencies subsequently served as the basis for constructing the preliminary Delphi questionnaire.

First round

In the first Delphi round, demographic and competency questionnaires were sent to 32 participants via email, allowing a two-week response period with two reminders to enhance the response rate. Participants rated each item on a Likert scale for necessity (1 = not necessary, 2 = useful but not necessary, 3 = necessary) and relevance (1 = not relevant, 2 = somewhat relevant, 3 = relevant, 4 = completely relevant). A consensus threshold of 75% agreement was applied for relevance ratings, while items with an average score ≥2.25 for necessity (75% of maximum) and ≥3 for relevance (75% of maximum) were retained [24,25]. The qualitative data were analyzed using conventional content analysis, identifying meaning units, coding, and categorizing them into preliminary competency items. This process ensured that all insights from participant interviews, including clarifications from follow-up interviews, were reflected in the questionnaire. All interviews were conducted and coded by a nurse. The data were reviewed and validated by three nursing professors. Integrating qualitative data into the Delphi rounds strengthened the comprehensiveness and validity of the competency items, in line with contemporary best practices for health research [24,25]. Credibility and dependability were ensured through peer debriefing and expert validation by three nursing professors.

Second round

At this stage, the items were assessed by participants based on their importance (unimportant = 1, slightly important = 2, important = 3, very important = 4). The objectives of the second round, instructions on how to complete the questionnaire, contact information for facilitators to resolve ambiguities, and the deadline for responding were provided to participants in both paper and email formats.

The response rate for the questionnaires at this stage was 94%. Items that received an average score of 3 or higher were included in the third round. Nine items did not meet the required score in this stage and were removed from the eligibility list.

Third round

At this stage, the questionnaire was reviewed by the participants for agreement (disagree = 0, agree = 1). The questionnaire return rate in this stage was 100%. Items that received an average score of 0.75 or higher were considered final items.

Quantitative data from the Delphi rounds were analyzed using SPSS version 16. Descriptive statistics, including mean, median, standard deviation, and interquartile range (IQR), were calculated for each competency item. The percentage of agreement among participants was calculated to determine consensus, with items achieving ≥75% agreement considered to have reached consensus. For necessity and relevance ratings, mean scores were compared against predefined thresholds (≥2.25 for necessity and ≥3 for relevance) to decide item retention. The interquartile range was also examined to assess dispersion of responses, providing insight into the degree of agreement among participants.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistical analyses were employed to summarize the panel responses across the Delphi rounds. Mean scores for necessity, relevance, and importance were calculated for each item, and item retention was determined according to predefined consensus thresholds. In the first round, items with ≥75% agreement, a mean necessity score ≥2.25, and a relevance score ≥3.0 were retained. In the second round, items with a mean importance score of 3.0 or higher advanced to the next round. In the final round, items with a mean agreement score of 0.75 or higher (representing 75% consensus) were accepted as final. Items not meeting these criteria were excluded from subsequent rounds. High mean agreement across rounds indicated a stable consensus among experts on the essential competencies required for ICU nurses.

Results

Out of 32 participants invited, 30 completed all Delphi rounds. Two ICU nurses did not respond in the first round and were consequently excluded from subsequent rounds (Table 1).

The reduction did not materially affect the results, as the remaining panel’s heterogeneity and adherence to the predefined consensus criteria remained unchanged. Data saturation was achieved after the fifth interview, with no new competency categories emerging thereafter. Similar or overlapping competency items identified from the interviews and the systematic review were systematically merged by the research team through iterative discussions before being presented to participants in the first Delphi round. The integrated pool of competencies, derived from both the systematic review and the qualitative interviews, formed the foundation for the Delphi questionnaire, ensuring that all items reflected both evidence-based and experiential aspects of ICU nursing competence.

The nursing profession within a country's healthcare system is critically important, as nurses are at the forefront of delivering healthcare services. One of the most essential parts of the hospital, where specialized nursing services hold particular importance, is the intensive care unit (ICU) [1]. Intensive care is founded on continuous monitoring, the preservation of vital body functions, and the continuity of care; therefore, nursing care in the ICU is highly specialized in nature [1,2]. Nurses working in intensive care units must possess the appropriate knowledge, skills, experience, and qualifications to adequately assess and respond to the complex needs of critically ill patients [3].

Since hospitalized patients have very complex clinical conditions, all aspects of care and treatment are addressed in a more detailed and specialized manner [4]. Thus, nursing care in these settings must be accompanied by professional competencies, which include the judicious and consistent application of technical and communication skills, clinical knowledge and reasoning, emotions, and values in clinical environments [5]. Furthermore, evaluating these competencies is essential to ensure adherence to minimum professional standards and readiness to fulfill the role effectively. The development of nurses' competencies is, in essence, an investment in ensuring the safety, quality, and efficiency of patient care [6]. The term "competence" is a complex concept in nursing, and various professional and academic institutions have provided different definitions and classifications regarding it. For instance, Sheribante (1996) identified three main categories of competence: professional competence, cognitive competence, and interpersonal skills [6]. The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) emphasizes eight competencies: clinical judgment, ethical advocacy, caring practices, collaboration, systems thinking, responsiveness to diversity, clinical curiosity, creativity, assessment, and facilitation of learning [7,8].

Two groups of individual factors, such as knowledge and skills, adherence to ethical and professional standards, respect for oneself and others, work experience, effective communication, interest in the profession, responsibility and accountability, and organizational factors, such as clinical and educational environment, retraining programs, control and supervision, and an efficient educational system, are effective in the process of nurses acquiring clinical competence [9]. Research has shown that one of the significant factors influencing clinical competence is work experience [10,11].

Another critical point is that the field of nursing is constantly evolving and growing. Based on the information obtained from the types of competencies and their respective priorities, educational program objectives are identified, and necessary actions are taken to develop appropriate curricula [12,13]. This includes determining the type and amount of resources needed to achieve these objectives and planning for suitable training [14].

A recent scoping review reveals significant variation in the use of competencies and the level of performance expected of intensive care nurses [15]. Recent syntheses demonstrate substantial heterogeneity in how competencies for intensive care nursing are defined, operationalised, and assessed across settings, undermining international consensus on expected performance levels for ICU nurses. Consequently, several national and local initiatives have sought to develop context-specific competency frameworks [16].

The increasing acuity and complexity of critically ill patients, together with advances in personalised, technology-driven care, further necessitate the delineation of advanced nursing competencies to support autonomous clinical decision-making in the ICU [17]. Importantly, translating internationally derived competency frameworks into local practice requires attention to country-specific constraints. In Iran, national surveys and qualitative studies report the following: (a) regulatory constraints: lack of a unified and nationally approved set of critical care nursing standards; (b) educational constraints: limited access to formal competency-based training programs at higher levels for critical care nurses; and (c) diversity of resources and work environment: heterogeneity in equipment, staffing levels, and workload across institutions, all of which may hinder implementation [18].

Objectives

This Delphi study was conducted to develop an expert-validated and context-sensitive competency framework for ICU nurses.

Methods

We conducted a three-round Delphi study to identify and explain the competencies required for intensive care unit (ICU) nurses. The Delphi method is a systematic and iterative technique used to achieve consensus among subject matter experts through a series of questionnaires and controlled feedback rounds (REF) [19]. To ensure transparency and methodological rigor, the study followed the CREDES guideline for the conduct and reporting of Delphi studies (REF) [20].

To allow critical appraisal of the methodology and the recommendations generated, our research adhered to CREDES, a guideline for the conduct and reporting of Delphi studies [20].

This study was conducted between January 2020 and December 2021.

The selection of 32 panel members was based on methodological recommendations for Delphi studies, which emphasize that an expert panel typically ranges from 8 to 50 participants, depending on the study scope and heterogeneity of expertise [21]. In Delphi research, the inclusion of a heterogeneous group of experts is essential to capture a wide range of perspectives, generate high-quality responses, and achieve a reliable consensus [22].

Considering the multidimensional nature of intensive care nursing and the aim to ensure representation of clinical, managerial, and educational viewpoints, a purposive sampling strategy with maximum variation was employed. The number of panel members exceeded the minimum requirement to compensate for potential attrition between Delphi rounds, which is a recognized limitation of electronic Delphi designs [22].

Participants

Considering the multidisciplinary nature of ICU care and the need for heterogeneity, 32 experts were purposively selected to ensure representation of clinical, managerial, and educational perspectives. The panel included: two intensive care fellowship physicians, three nursing faculty members, three head nurses, eight master 's-level ICU nurses, eleven bachelor-level ICU nurses, and five postgraduate ICU nursing students (third semester and above). Inclusion criteria were: a minimum of five years of continuous ICU experience, current employment in adult general ICUs, and willingness to participate through all rounds. Nurses working primarily in neonatal or pediatric ICUs were excluded.

This study was conducted in four stages: Development of the questionnaire (qualitative interviews and systematic review), first round (presentation of the questionnaire formed in the preliminary stage, scoring the "necessity" and "relevance" of the items), second round (presentation of the results of the first round, presentation of the questionnaire for scoring the "importance" of the items), and third round (presentation of the results of the second round, presentation of the questionnaire in terms of "agreement" of the items)

Development of the questionnaire

This stage included qualitative interviews and systematic reviews. Interviews were conducted with three nurses and two head nurses who had a master's degree in critical care nursing and were working in the critical care unit.

Data were collected through in-depth, semi-structured individual interviews using a conventional content analysis approach as described by Hsieh and Shannon [23]. This approach was chosen because it allows categories and themes to emerge inductively from the data without imposing preconceived frameworks. Interviews were conducted by the first author, who was trained in qualitative research, in a quiet room within the ICU to ensure participants’ comfort and confidentiality. Each interview lasted between 40 and 70 minutes, depending on the participant’s willingness to elaborate on their experiences.

The interview guide included open-ended questions such as, “What competencies do you consider essential for nurses working in the ICU?” and “How do you demonstrate professional competence in critical situations?” Follow-up probes were used to encourage clarification and elaboration. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim immediately after each session, and reviewed for accuracy against the recordings.

Data analysis began simultaneously with data collection. Transcripts were read several times to achieve immersion in the data. Meaning units were identified, condensed, and labeled with codes, which were then grouped into subcategories and categories based on similarities and differences. Coding and categorization were performed manually and verified by two independent researchers to enhance analytic rigor.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted to identify studies published between January 1990 to September 2020. English databases, including SCOPUS, PubMed, OVID, ScienceDirect, ProQuest, and Persian databases such as Magiran and Google Scholar for grey literature. The following keywords were used: (“competency” OR “competencies” OR “clinical competence” OR “core competencies”) AND (“nurse*” OR “intensive care nurse*”) AND (“ICU” OR “intensive care unit”) AND (“professionalism” OR “clinical performance” OR “Professional Behavior” OR “criteria” OR “Professional Behavior”). Boolean operators AND and OR were used to combine the keywords.Data Integration and Saturation Criteria

To ensure methodological rigor, data saturation and integration procedures were carefully defined. Data saturation was achieved when no new competencies or themes emerged from the final two interviews, indicating that the qualitative data had sufficient depth and comprehensiveness.

To integrate the results of the qualitative phase with findings from the systematic review, all extracted competencies and skill items were organized in a unified comparison matrix. The research team independently reviewed and coded overlapping or conceptually similar items through iterative discussions until complete consensus was reached. This process ensured that both empirically derived competencies from the literature and contextually grounded insights from expert interviews were merged into a single, comprehensive competency framework. The integrated list of competencies subsequently served as the basis for constructing the preliminary Delphi questionnaire.

First round

In the first Delphi round, demographic and competency questionnaires were sent to 32 participants via email, allowing a two-week response period with two reminders to enhance the response rate. Participants rated each item on a Likert scale for necessity (1 = not necessary, 2 = useful but not necessary, 3 = necessary) and relevance (1 = not relevant, 2 = somewhat relevant, 3 = relevant, 4 = completely relevant). A consensus threshold of 75% agreement was applied for relevance ratings, while items with an average score ≥2.25 for necessity (75% of maximum) and ≥3 for relevance (75% of maximum) were retained [24,25]. The qualitative data were analyzed using conventional content analysis, identifying meaning units, coding, and categorizing them into preliminary competency items. This process ensured that all insights from participant interviews, including clarifications from follow-up interviews, were reflected in the questionnaire. All interviews were conducted and coded by a nurse. The data were reviewed and validated by three nursing professors. Integrating qualitative data into the Delphi rounds strengthened the comprehensiveness and validity of the competency items, in line with contemporary best practices for health research [24,25]. Credibility and dependability were ensured through peer debriefing and expert validation by three nursing professors.

Second round

At this stage, the items were assessed by participants based on their importance (unimportant = 1, slightly important = 2, important = 3, very important = 4). The objectives of the second round, instructions on how to complete the questionnaire, contact information for facilitators to resolve ambiguities, and the deadline for responding were provided to participants in both paper and email formats.

The response rate for the questionnaires at this stage was 94%. Items that received an average score of 3 or higher were included in the third round. Nine items did not meet the required score in this stage and were removed from the eligibility list.

Third round

At this stage, the questionnaire was reviewed by the participants for agreement (disagree = 0, agree = 1). The questionnaire return rate in this stage was 100%. Items that received an average score of 0.75 or higher were considered final items.

Quantitative data from the Delphi rounds were analyzed using SPSS version 16. Descriptive statistics, including mean, median, standard deviation, and interquartile range (IQR), were calculated for each competency item. The percentage of agreement among participants was calculated to determine consensus, with items achieving ≥75% agreement considered to have reached consensus. For necessity and relevance ratings, mean scores were compared against predefined thresholds (≥2.25 for necessity and ≥3 for relevance) to decide item retention. The interquartile range was also examined to assess dispersion of responses, providing insight into the degree of agreement among participants.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistical analyses were employed to summarize the panel responses across the Delphi rounds. Mean scores for necessity, relevance, and importance were calculated for each item, and item retention was determined according to predefined consensus thresholds. In the first round, items with ≥75% agreement, a mean necessity score ≥2.25, and a relevance score ≥3.0 were retained. In the second round, items with a mean importance score of 3.0 or higher advanced to the next round. In the final round, items with a mean agreement score of 0.75 or higher (representing 75% consensus) were accepted as final. Items not meeting these criteria were excluded from subsequent rounds. High mean agreement across rounds indicated a stable consensus among experts on the essential competencies required for ICU nurses.

Results

Out of 32 participants invited, 30 completed all Delphi rounds. Two ICU nurses did not respond in the first round and were consequently excluded from subsequent rounds (Table 1).

The reduction did not materially affect the results, as the remaining panel’s heterogeneity and adherence to the predefined consensus criteria remained unchanged. Data saturation was achieved after the fifth interview, with no new competency categories emerging thereafter. Similar or overlapping competency items identified from the interviews and the systematic review were systematically merged by the research team through iterative discussions before being presented to participants in the first Delphi round. The integrated pool of competencies, derived from both the systematic review and the qualitative interviews, formed the foundation for the Delphi questionnaire, ensuring that all items reflected both evidence-based and experiential aspects of ICU nursing competence.

| Subjects | First Round | Second Round | Third Round | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Intensive care fellowship physicians | 2 | 6.25 | 2 | 6.66 | 2 | 6.66 |

| Nursing faculty members | 3 | 9.38 | 3 | 10.00 | 3 | 10.00 |

| Head nurses | 3 | 9.38 | 3 | 10.00 | 3 | 10.00 |

| Master's in Intensive Care Nursing | 8 | 25.00 | 8 | 26.60 | 8 | 26.60 |

| Master's student in intensive care | 5 | 15.63 | 5 | 16.66 | 5 | 16.66 |

| Bachelor's nurses | 11 | 34.40 | 9 | 30.00 | 9 | 30.00 |

| Total | 32 | 100.00 | 30 | 100.00 | 30 | |

The average age of the study subjects was 43.73 (13.23) years, with a total work experience of 17.1 (8.42) years (ICU work experience: 10.67 (4.98)). Weekly work hours were 49 (43.5-62.5). The most significant number of participants belonged to the group of nurses with a bachelor's degree, and the smallest to the group of intensive care fellows. The demographic characteristics of the populations are presented in Table 2.

At the stage of developing the questionnaire, items introduced by the interviewees as competencies or skills were coded. After merging similar codes, a total of 80 items were extracted. 24 articles and 5 theses that were most relevant to the topic were selected in the systematic review stage, and a total of 198 items were extracted.

After re-evaluating the 278 items obtained from the two systematic and interview stages, 71 items were removed due to overlap and repetition. A final questionnaire comprising 207 items was then formed (supplementary data). A content analysis of existing nursing role descriptions was conducted to identify the competencies required by intensive care unit nurses, yielding 17 competency domains (Table 3).

Table 2. Demographic Characteristics of the Delphi Panel Experts (N = 32)

| Demographic Variables | n | % |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 18 | 56.25 |

| Female | 14 | 43.75 |

| Academic Education Related to ICU | ||

| Yes | 21 | 65.62 |

| No | 11 | 34.38 |

| Highest Educational Degree | ||

| ICU Specialist | 2 | 6.25 |

| Doctor of Philosophy | 1 | 3.13 |

| Master's | 13 | 40.63 |

| Bachelor's | 16 | 50.00 |

| ICU Short Course | ||

| Yes | 28 | 87.50 |

| No | 4 | 12.50 |

Table 3. Competency Categories for Nurses Working in Intensive Care Units, with Example Items and Ratings

| Category | Example Item | Necessity | Relevance | Importance | Agreement | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| 1. Personality Traits | Have honesty, altruism, and confidentiality. | 3.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Have sufficient motivation for patient care. | 2.97 | 0.18 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| 2. Nursing Process | Perform comprehensive patient assessment. | 2.67 | 0.61 | 3.30 | 0.99 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 0.93 | 0.25 |

| Identify correct nursing diagnoses. | 2.67 | 0.61 | 3.26 | 1.02 | 3.12 | 1.05 | 0.97 | 0.18 | |

| 3. Comprehensive Therapeutic Care | Provide comprehensive care to varied patients. | 2.77 | 0.50 | 3.07 | 1.14 | 3.17 | 1.25 | 0.93 | 0.25 |

| Modify care plans to improve quality. | 2.57 | 0.77 | 3.14 | 1.23 | 3.15 | 1.22 | 0.93 | 0.25 | |

| 4. Evidence-Based Care | Apply current research to practice. | 2.90 | 0.30 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Critically appraise evidence. | 2.80 | 0.48 | 3.90 | 0.10 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.18 | |

| 5. Safe Care/Safety | Implement infection control guidelines. | 2.70 | 0.65 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Identify and minimize safety risks. | 2.83 | 0.46 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| 6. Professionalism | Demonstrate professional conduct. | 2.83 | 0.46 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Maintain up-to-date knowledge. | 2.87 | 0.43 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 0.93 | 0.25 | |

| 7. Ethics/Conscience | Apply nursing code of ethics. | 2.70 | 0.60 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 0.93 | 0.25 |

| Respect patient dignity and privacy. | 2.67 | 0.61 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.18 | |

| 8. Communication Skills | Communicate effectively. | 2.90 | 0.30 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Demonstrate active listening. | 2.83 | 0.46 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| 9. Teamwork and Collaboration | Cooperate with healthcare team. | 2.80 | 0.41 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Respect team opinions. | 2.83 | 0.38 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 3.90 | 0.10 | 0.97 | 0.18 | |

| 10. Critical Thinking | Analyze complex situations. | 2.80 | 0.41 | 3.90 | 0.10 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.18 |

| Make sound clinical decisions. | 2.83 | 0.46 | 3.93 | 0.18 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| 11. Leadership and Management | Coordinate care in emergencies. | 2.87 | 0.43 | 3.97 | 0.10 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Delegate tasks appropriately. | 2.80 | 0.48 | 3.90 | 0.10 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.18 | |

| 12. Teaching and Mentoring | Educate patients and families. | 2.77 | 0.50 | 3.87 | 0.20 | 3.97 | 0.10 | 0.97 | 0.18 |

| Mentor novice nurses. | 2.73 | 0.64 | 3.90 | 0.10 | 3.97 | 0.10 | 0.93 | 0.25 | |

| 13. Research and Development | Participate in research. | 2.67 | 0.61 | 3.70 | 0.45 | 3.87 | 0.30 | 0.90 | 0.30 |

| Use research to improve practice. | 2.80 | 0.48 | 3.87 | 0.20 | 3.97 | 0.10 | 0.97 | 0.18 | |

| 14. Professional Development | Engage in continuous education. | 2.87 | 0.35 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Reflect on personal performance. | 2.83 | 0.38 | 3.97 | 0.10 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.18 | |

| 15. Legal Awareness | Recognize legal aspects. | 2.77 | 0.50 | 3.83 | 0.37 | 3.90 | 0.30 | 0.93 | 0.25 |

| Report incidents legally. | 2.80 | 0.48 | 3.97 | 0.10 | 3.93 | 0.25 | 0.97 | 0.18 | |

| 16. Cultural/Spiritual Competence | Respect diverse beliefs. | 2.83 | 0.46 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.18 |

| Provide culturally sensitive care. | 2.77 | 0.57 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.18 | |

| 17. Documentation and Reporting | Record information accurately. | 2.87 | 0.43 | 3.97 | 0.10 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Maintain complete and timely reports. | 2.83 | 0.46 | 3.93 | 0.18 | 3.97 | 0.10 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

Discussion

The present study identified 17 core competency categories as essential qualifications for nurses working in intensive care units (ICUs). Among these, competencies related to professionalism, patient safety, communication skills, critical thinking, and evidence-based care received the highest priority scores, reflecting the multidimensional nature of ICU nursing practice. These findings are consistent with previous research highlighting the critical role of cognitive, ethical, and interpersonal skills in ensuring high-quality and safe care in critical settings. For example, an Iranian study reported that both individual characteristics (such as work experience, education level, and emotional intelligence) and organizational-environmental factors (such as cultural understanding, job satisfaction, and collaboration with colleagues) influence nurses’ clinical competence. Similar to the current results, these studies emphasize that professional competence in ICUs extends beyond technical expertise and encompasses personal and contextual capabilities essential for effective performance [26].

Possible differences arising from the main categories of the present study may be attributed to other sources for various reasons. The working conditions in the intensive care unit are different from other departments (such as emergency rooms and inpatient wards). Therefore, it is not far-fetched to expect that the qualifications of nurses working in intensive care units will be different from those of nurses in other clinical departments. The nature of intensive care units (ICUs) indicates that the characteristics of the work environment and the structure of the unit significantly influence patient care practices [27].

Differences in equipment and facilities used in intensive care units compared to other units can also lead to some variations in findings. A study by Nobahar et al. showed that the structure of the ward and its facilities affect the quality of care [28]. Nursing care in a highly technological setting should be viewed as complex in terms of its impact on the experiences of Critical Care Nurses (CCNs). The sophisticated care provided in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) relies heavily on advanced medical equipment, yet it also depends on effective interpersonal communication and foundational nursing practices. While technology serves as a crucial resource, it can also pose challenges to delivering patient-centered care [29]. Given the advancement of science and technology, the equipment and facilities used in intensive care units are also evolving. Therefore, it is necessary for nurses working in these units to receive training on how to operate the devices and care for patients. In-service training, focusing on the use of facilities and equipment, and enhancing the technical knowledge of nurses, is mandatory. Therefore, head nurses and nursing managers should make the necessary plans in planning the training of nurses in this field [30,31].

The possession of specific skills before admission in many countries is a requirement for employment in the intensive care sector (in addition to a clinical competence license). In contrast, Iran lacks a written standard or guideline for recruitment in these areas. The prerequisites and competencies that individuals should possess have been overlooked. The inappropriate distribution of nursing staff is evident, as nurses who have studied for a Master's degree in Intensive Care Nursing often work in unrelated fields and typically do not transition to intensive care units after graduation.

The introduction of training programs specifically designed for critical care nurses proved advantageous for both the nurses themselves and the healthcare system. These training initiatives concentrated on enhancing the skills and knowledge relevant to various phases of their careers [32].

Critical thinking/clinical judgment were other clinical competencies in this study. Nurses are making decisions every 30 seconds in one of the areas of nursing interventions, assessing patients' clinical status, and communication processes [33]. About 34% of what happens to patients in hospitals in the UK is due to poor decision-making by nurses, of which 6% of patients suffer permanent disability and 8% die. While a quarter of these deaths could have been prevented by timely decision-making by nurses [34]. Critical thinking and clinical decision-making are part of the recommended nursing competencies [35].

It should be noted that nursing graduates need to be aware of the roles and responsibilities of nurses, in addition to acquiring the competence to care for patients, how to adapt to issues such as organizing care efficiently and effectively, performing nursing tasks promptly, and how to work with new colleagues [36].

From a management perspective, the competence of nurses is an effective factor in ensuring the quality of care provided to patients and obtaining their satisfaction, and in today's competitive world, it is a key component in the survival of hospitals [37]. In the clinical field, changes in the roles and responsibilities of nurses, which have transformed nursing into a complex profession requiring diverse skills, have led to increased attention to clinical competence.

The findings of this study help address several existing limitations in the Iranian context of intensive care nursing. In Iran, there is currently no formal guideline or standardized requirement for recruitment into critical care units, resulting in inappropriate distribution of nursing staff and a lack of clarity regarding the competencies expected of ICU nurses. By identifying 17 core competency categories, this study provides a comprehensive framework that defines the essential skills, knowledge, and attributes required for effective ICU practice.

This framework highlights areas for targeted training, professional development, and workforce planning, ensuring that nurses possess the necessary competencies before employment or advancement in critical care settings. Establishing these standards not only supports optimal patient care and safety but also guides nursing managers in quality assurance, educational planning, and human resource management, thereby addressing key gaps previously observed in Iranian critical care nursing practice.

Conclusion

the present study provides a comprehensive framework of 185 competency items across 17 categories that define the essential skills, knowledge, and attitudes required for nurses in intensive care units. These competencies encompass both technical and non-technical domains, reflecting the complex and high-stakes nature of ICU practice. The findings emphasize that ensuring clinical competence is not only critical for patient safety and quality of care but also central to workforce planning, educational curriculum design, and ongoing professional development. Structured training programs, targeted in-service education, and management support are crucial to equip nurses with the necessary competencies, particularly in rapidly evolving and technologically advanced ICU environments. By establishing a standardized competency framework, this study contributes to evidence-based guidance for nursing practice, addresses gaps in current clinical standards, and facilitates the preparation of nurses to meet the increasing demands and challenges of critical care. Our study has limitations. We had two attrations in the second and third rounds, which is familiar with the prolonged nature of the Delphi process. Additionally, due to the study's length, the competencies achieved by nurses were not validated; therefore, it is recommended that a pilot study be conducted in the future. Furthermore, there is a lack of clear guidance and standardized criteria for interpreting and analyzing the Delphi results, as well as universally accepted definitions of consensus and established methods for participant selection.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of YAZD University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.SSU.REC.1398.070). All participants entered this study with their personal and informed consent.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to all participants. The article is extracted from the thesis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

No

Authors' contributions

Data collection: Setavand MR, Jvadi M; Writing the original draft, review, and editing:Hosseini SE; Conceptualization, study design, data analysis, data interpretation, and final approval: All authors

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

The article was not written using artificial intelligence.

Data availability statement

The data are available from the corresponding author.

The present study identified 17 core competency categories as essential qualifications for nurses working in intensive care units (ICUs). Among these, competencies related to professionalism, patient safety, communication skills, critical thinking, and evidence-based care received the highest priority scores, reflecting the multidimensional nature of ICU nursing practice. These findings are consistent with previous research highlighting the critical role of cognitive, ethical, and interpersonal skills in ensuring high-quality and safe care in critical settings. For example, an Iranian study reported that both individual characteristics (such as work experience, education level, and emotional intelligence) and organizational-environmental factors (such as cultural understanding, job satisfaction, and collaboration with colleagues) influence nurses’ clinical competence. Similar to the current results, these studies emphasize that professional competence in ICUs extends beyond technical expertise and encompasses personal and contextual capabilities essential for effective performance [26].

Possible differences arising from the main categories of the present study may be attributed to other sources for various reasons. The working conditions in the intensive care unit are different from other departments (such as emergency rooms and inpatient wards). Therefore, it is not far-fetched to expect that the qualifications of nurses working in intensive care units will be different from those of nurses in other clinical departments. The nature of intensive care units (ICUs) indicates that the characteristics of the work environment and the structure of the unit significantly influence patient care practices [27].

Differences in equipment and facilities used in intensive care units compared to other units can also lead to some variations in findings. A study by Nobahar et al. showed that the structure of the ward and its facilities affect the quality of care [28]. Nursing care in a highly technological setting should be viewed as complex in terms of its impact on the experiences of Critical Care Nurses (CCNs). The sophisticated care provided in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) relies heavily on advanced medical equipment, yet it also depends on effective interpersonal communication and foundational nursing practices. While technology serves as a crucial resource, it can also pose challenges to delivering patient-centered care [29]. Given the advancement of science and technology, the equipment and facilities used in intensive care units are also evolving. Therefore, it is necessary for nurses working in these units to receive training on how to operate the devices and care for patients. In-service training, focusing on the use of facilities and equipment, and enhancing the technical knowledge of nurses, is mandatory. Therefore, head nurses and nursing managers should make the necessary plans in planning the training of nurses in this field [30,31].

The possession of specific skills before admission in many countries is a requirement for employment in the intensive care sector (in addition to a clinical competence license). In contrast, Iran lacks a written standard or guideline for recruitment in these areas. The prerequisites and competencies that individuals should possess have been overlooked. The inappropriate distribution of nursing staff is evident, as nurses who have studied for a Master's degree in Intensive Care Nursing often work in unrelated fields and typically do not transition to intensive care units after graduation.

The introduction of training programs specifically designed for critical care nurses proved advantageous for both the nurses themselves and the healthcare system. These training initiatives concentrated on enhancing the skills and knowledge relevant to various phases of their careers [32].

Critical thinking/clinical judgment were other clinical competencies in this study. Nurses are making decisions every 30 seconds in one of the areas of nursing interventions, assessing patients' clinical status, and communication processes [33]. About 34% of what happens to patients in hospitals in the UK is due to poor decision-making by nurses, of which 6% of patients suffer permanent disability and 8% die. While a quarter of these deaths could have been prevented by timely decision-making by nurses [34]. Critical thinking and clinical decision-making are part of the recommended nursing competencies [35].

It should be noted that nursing graduates need to be aware of the roles and responsibilities of nurses, in addition to acquiring the competence to care for patients, how to adapt to issues such as organizing care efficiently and effectively, performing nursing tasks promptly, and how to work with new colleagues [36].

From a management perspective, the competence of nurses is an effective factor in ensuring the quality of care provided to patients and obtaining their satisfaction, and in today's competitive world, it is a key component in the survival of hospitals [37]. In the clinical field, changes in the roles and responsibilities of nurses, which have transformed nursing into a complex profession requiring diverse skills, have led to increased attention to clinical competence.

The findings of this study help address several existing limitations in the Iranian context of intensive care nursing. In Iran, there is currently no formal guideline or standardized requirement for recruitment into critical care units, resulting in inappropriate distribution of nursing staff and a lack of clarity regarding the competencies expected of ICU nurses. By identifying 17 core competency categories, this study provides a comprehensive framework that defines the essential skills, knowledge, and attributes required for effective ICU practice.

This framework highlights areas for targeted training, professional development, and workforce planning, ensuring that nurses possess the necessary competencies before employment or advancement in critical care settings. Establishing these standards not only supports optimal patient care and safety but also guides nursing managers in quality assurance, educational planning, and human resource management, thereby addressing key gaps previously observed in Iranian critical care nursing practice.

Conclusion

the present study provides a comprehensive framework of 185 competency items across 17 categories that define the essential skills, knowledge, and attitudes required for nurses in intensive care units. These competencies encompass both technical and non-technical domains, reflecting the complex and high-stakes nature of ICU practice. The findings emphasize that ensuring clinical competence is not only critical for patient safety and quality of care but also central to workforce planning, educational curriculum design, and ongoing professional development. Structured training programs, targeted in-service education, and management support are crucial to equip nurses with the necessary competencies, particularly in rapidly evolving and technologically advanced ICU environments. By establishing a standardized competency framework, this study contributes to evidence-based guidance for nursing practice, addresses gaps in current clinical standards, and facilitates the preparation of nurses to meet the increasing demands and challenges of critical care. Our study has limitations. We had two attrations in the second and third rounds, which is familiar with the prolonged nature of the Delphi process. Additionally, due to the study's length, the competencies achieved by nurses were not validated; therefore, it is recommended that a pilot study be conducted in the future. Furthermore, there is a lack of clear guidance and standardized criteria for interpreting and analyzing the Delphi results, as well as universally accepted definitions of consensus and established methods for participant selection.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of YAZD University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.SSU.REC.1398.070). All participants entered this study with their personal and informed consent.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to all participants. The article is extracted from the thesis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

No

Authors' contributions

Data collection: Setavand MR, Jvadi M; Writing the original draft, review, and editing:Hosseini SE; Conceptualization, study design, data analysis, data interpretation, and final approval: All authors

Artificial intelligence utilization for article writing

The article was not written using artificial intelligence.

Data availability statement

The data are available from the corresponding author.

Type of Study: Orginal research |

Subject:

Nursing

References

1. Tajari M, Ashktorab T, Ebadi A. Components of safe nursing care in the intensive care units: a qualitative study. BMC Nursing. 2024;23(1):613. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02180-9] [PMID]

2. Goñi-Viguria R. Experience of an advanced practice nurse in an intensive care unit. Enfermería Intensiva (English Edition). 2025;36(1):100482. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfie.2025.100482] [PMID]

3. Zarei F, Dehghan M, Shahrbabaki PM. The relationship between perception of good death with clinical competence of end-of-life care in critical care nurses. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying. 2025;91(1):401-417.

https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228221134721 [https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228231155321] [PMID]

4. Pashaee S, Lakdizaji S, Rahmani A, Zamanzadeh V. Priorities of caring behaviors from critical care nurses viewpoints. Preventive Care in Nursing & Midwifery Journal. 2014;4(1):65-73. [http://pcnmj.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-155-en.html]

5. Perez-Gonzalez S, Marques-Sanchez P, Pinto-Carral A, Gonzalez-Garcia A, Liebana-Presa C, Benavides C. Characteristics of leadership competency in nurse managers: a scoping review. Journal of Nursing Management. 2024;2024(1):5594154. [https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/5594154] [PMID]

6. Coventry TH, Maslin-Prothero SE, Smith G. Organizational impact of nurse supply and workload on nurses continuing professional development opportunities: an integrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2015;71(12):2715-2727. [https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12724] [PMID]

7. Bahreini M, Moattari M, Kaveh MH, Ahmadi F. A Comparison of Nurses' Clinical Competences in Two Hospitals Affiliated to Shiraz and Boushehr Universities of Medical Sciences: A Self-Assessment. Iranian Journal of Medical Education. 2010;10(2):155-163. [http://ijme.mui.ac.ir/article-1-1253-en.html]

8. Zaitoun RA. Assessing nurses' professional competency: a cross-sectional study in Palestine. BMC Nursing. 2024;23(1):379. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02064-y] [PMID]

9. Baik D, Yi N, Han O, Kim Y. Trauma nursing competency in the emergency department: a concept analysis. BMJ Open. 2024;14(6):e079259. [https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-079259] [PMID]

10. Rizany I, Hariyati RTS, Handayani H. Factors that affect the development of nurses' competencies: a systematic review. Enfermeria Clinica. 2018;28:154-157. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfcli.2018.04.007] [PMID]

11. Almarwani AM, Alzahrani NS. Factors affecting the development of clinical nurses' competency: A systematic review. Nurse Education in Practice. 2023;73:103826. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2023.103826] [PMID]

12. Vafaee Najar A, Habashizade A, Karimi H, Ebrahimzade S. The effect of improvement of nursing managers' professional competencies based on performance on their productivity: An interventional study. Daneshvar Medicine. 2011;19(3):63-72. [http://daneshvarmed.shahed.ac.ir/article-1-456-en.html]

13. Kim HW, Kim MG. The relationship among academic achievement, clinical competence, and confidence in clinical performance of nursing students. The Journal of Korean Academic Society of Nursing Education. 2021;27(1):49-58. [https://doi.org/10.5977/jkasne.2021.27.1.49]

14. Le TTH, Aliswag EG. Quality of nursing care, compassionate care and patient satisfaction: A multiple regression in path analysis model. Journal of Nursing Science. 2025;8(01):17-28. [https://doi.org/10.54436/jns.2025.01.940]

15. Egerod I, Kaldan G, Nordentoft S, Larsen A, Herling SF, Thomsen T, et al. Skills, competencies, and policies for advanced practice critical care nursing in Europe: A scoping review. Nurse Education in Practice. 2021;54:103142. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103142] [PMID]

16. Kaldan G, Nordentoft S, Herling SF, Larsen A, Thomsen T, Egerod I. Evidence characterising skills, competencies and policies in advanced practice critical care nursing in Europe: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e031504. [https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031504] [PMID]

17. Saqib M. Trends in Critical Care Medicine: Innovations Shaping the Future. In: Advances in Medical Technology. Springer; 2025:45-62. [https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.1010714]

18. Farsi Z, Nasiri M, Sajadi SA, Khavasi M. Comparison of Iran's nursing education with developed and developing countries: a review on descriptive-comparative studies. BMC Nursing. 2022;21(1):105. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-022-00880-8] [PMID]

19. Keeney S, McKenna HP, Hasson F. The Delphi Technique in Nursing and Health Research. John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444392029]

20. Jünger S, Payne SA, Brine J, Radbruch L, Brearley SG. Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: Recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliative Medicine. 2017;31(8):684-706. [https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216317690685] [PMID]

21. Hohmann E, Beaufils P, Beiderbeck D, Chahla J, Geeslin A, Hasan S, et al. Guidelines for designing and conducting Delphi consensus studies: an expert consensus Delphi study. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2025;41(1):12-25. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2024.08.045] [PMID]

22. Shang Z. Use of Delphi in health sciences research: a narrative review. Medicine. 2023;102(7):e32829. [https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000032829] [PMID]

23. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277-1288. [https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687] [PMID]

24. Lim WM. What is qualitative research? An overview and guidelines. Australasian Marketing Journal. 2025;33(2):199-229. [https://doi.org/10.1177/14413582241264619]

25. del Pozo-Herce P, Martínez-Sabater A, Chover-Sierra E, Gea-Caballero V, Satústegui-Dordá PJ, Saus-Ortega C, et al. Application of the Delphi method for content validity analysis of a questionnaire to determine the risk factors of the Chemsex. Healthcare. 2023;11(5):742. [https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11050742] [PMID]

26. Najafi B, Nakhaei M. Clinical competence of nurses: a systematic review study. Journal of Nursing Education. 2022;11(2):45-56. [https://doi.org/10.21859/ijn-11025]

27. Yoo HJ, Lim OB, Shim JL. Critical care nurses' communication experiences with patients and families in an intensive care unit: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0235694. [https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235694] [PMID]

28. Nobahar M. Care quality in critical cardiac units from nurses perspective: A content analysis. Journal of Qualitative Research in Health Sciences. 2014;3(2):149-161. [http://jqr1.kmu.ac.ir/article-1-256-en.html]

29. Tunlind A, Granström J, Engström Å. Nursing care in a high-technological environment: Experiences of critical care nurses. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2015;31(2):116-123. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2014.11.005] [PMID]

30. Kanjakaya P. Nurses perceptions regarding the use of technological equipment in the intensive care unit setting of a public sector hospital in Johannesburg [master's thesis]. University of the Witwatersrand; 2014. [http://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/handle/10539/15347]

31. O'Connell M, Reid B, O'Loughlin K. An exploration of the education and training experiences of ICU nurses in using computerised equipment. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;25(2):46-52. [https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.838909887356254]

32. Santana-Padilla YG, Bernat-Adell MD, Santana-Cabrera L. Nurses' perception on competency requirement and training demand for intensive care nurses. International Journal of Nursing Sciences. 2022;9(3):350-356. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2022.06.004] [PMID]

33. Bucknall TK. Critical care nurses' decision-making activities in the natural clinical setting. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2000;9(1):25-36. [https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2702.2000.00360.x] [PMID]

34. Thompson C, Aitken L, Doran D, Dowding D. An agenda for clinical decision making and judgement in nursing research and education. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2013;50(12):1720-1726. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.07.005] [PMID]

35. Hwang GJ, Cheng PY, Chang CY. Facilitating students' critical thinking, metacognition and problem-solving tendencies in geriatric nursing class: A mixed-method study. Nurse Education in Practice. 2025;83:104266. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2025.104266] [PMID]

36. Baharum H, Ismail A, McKenna L, Mohamed Z, Ibrahim R, Hassan NH. Success factors in adaptation of newly graduated nurses: a scoping review. BMC Nursing. 2023;22(1):125. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01279-9] [PMID]

37. Ortega-Lapiedra R, Barrado-Narvión MJ, Bernués-Oliván J. Acquisition of competencies of nurses: improving the performance of the healthcare system. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023;20(5):4510. [https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054510] [PMID]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |