Preventive Care in Nursing and Midwifery Journal

Volume 15, Issue 4 (10-2025)

Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J 2025, 15(4): 6-18 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.ZUMS.REC.1396.334

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Azadi Z, Kharghani R, Emamgholi khooshehchin T, Ebrahimi L. The Effect of Cognitive Behavioral Counseling on Stress and Quality of Life of Pregnant Women with a History of Spontaneous Abortion: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J 2025; 15 (4) :6-18

URL: http://nmcjournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-980-en.html

URL: http://nmcjournal.zums.ac.ir/article-1-980-en.html

Department of Midwifery, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Iran , khoosheh@zums.ac.ir

Keywords: Individual Counseling, Cognitive-Behavioral Approach, Stress, Quality of Life, Spontaneous Abortion

Full-Text [PDF 1067 kb]

(58 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (190 Views)

Table 4. Post-hoc Comparisons of Stress and Quality of Life Scores across Time Points Using the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test

For the physical domain, a significant improvement was found only at the two-month follow-up compared to baseline (p = 0.004). No significant differences were observed between the post-intervention and two-month follow-up scores for any variable in the intervention group (all p > 0.05), indicating the improvements were sustained.

In contrast, within the control group, none of the pairwise comparisons between the three time points reached statistical significance for any of the measured variables (all p > 0.05) (Table 4).

Discussion

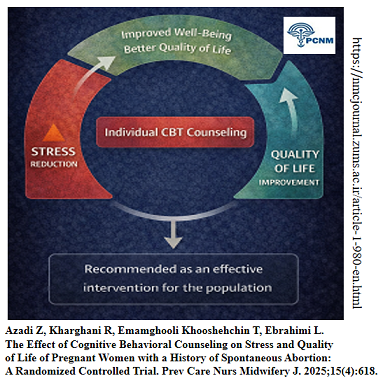

The findings of this clinical trial demonstrate that individually administered cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) significantly reduced stress and improved quality of life among pregnant women with a history of spontaneous abortion. Significant differences between the intervention and control groups were observed post-intervention immediately and were sustained at the two-month follow-up across stress levels and most quality-of-life domains. The intervention yielded a very large effect on stress reduction (Kendall’s W = 0.771) and a large effect on improving psychological well-being (Kendall’s W = 0.607), with medium effects observed for the social domain and small-to-medium effects for the environmental domain. This provides robust evidence for the durable efficacy of a structured, face-to-face CBT protocol in enhancing psychological health during a subsequent pregnancy.

The observed reduction in stress aligns with findings from other studies that employed various counseling approaches for pregnant women with a history of pregnancy loss [12, 22, 23]. While the literature confirms that psychological interventions can alleviate stress, many prior studies have focused on women with recurrent miscarriage, and interventions have often been educational or lacked a standardized theoretical foundation [12,22]. This study addresses notable gaps by targeting women with a single prior miscarriage, an often-overlooked population, and implementing a manualized CBT protocol. The inclusion of a two-month follow-up further demonstrates the sustainability of the benefits, suggesting the acquisition of lasting coping skills.

The positive impact of CBT on multiple quality of life domains is consistent with prior research. Heratzadeh et al. reported similar benefits on quality of life from self-compassion training [24], while Silva et al. found CBT improved quality of life and social functioning post-miscarriage [18]. Furthermore, Hiltunen et al. indicated that CBT could enhance quality of life even when delivered by less experienced therapists [32]. The mechanism through which CBT confers benefit can be explained by its focus on modifying cognitive and behavioral responses to stress. Through cognitive restructuring, individuals develop rational self-talk, which reduces psychological distress in anxiety-provoking situations [33]. Techniques such as behavioral activation help counteract depression and amotivation by increasing engagement in pleasurable activities, thereby revitalizing motivation and life satisfaction through the modification of core beliefs [34].

The lack of a significant effect in the physical domain of quality of life may be attributable to the predominant hormonal and physiological changes of pregnancy, which are less amenable to psychosocial intervention. However, as the primary challenges for this population are psychological, CBT remains a highly suitable supportive approach. This study has several limitations that should be considered. First, the reliance on self-report measures may introduce response bias. Second, participant retention challenges occurred, and the small sample size, drawn from a specific geographic area, limits the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. The small sample size also restricted our ability to conduct more robust analyses of interaction effects and to report a comprehensive range of effect size measures. Third, the inability to blind participants to the intervention and the lack of blinding for outcome assessors may have introduced performance and measurement bias, particularly for self-reported outcomes like quality of life. Finally, the lack of an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, due to dropout, may have influenced the effect size estimates, potentially overstating the intervention's efficacy. Despite these limitations, a key strength is the use of individual, face-to-face CBT counseling, which facilitated open emotional expression, personalized feedback, and structured between-session assignments to promote skill acquisition and reflection.In conclusion, individual CBT counseling appears to be an effective and sustainable intervention for reducing stress and improving quality of life in pregnant women with a prior miscarriage. Future research with larger, more diverse samples and rigorous methodological designs, including blinded outcome assessment and ITT analysis, is recommended to confirm these findings and facilitate the integration of this approach into standard perinatal mental health pathways.

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that individual cognitive-behavioral counseling may help reduce stress and improve most domains of quality of life in pregnant women with a history of spontaneous abortion. These findings contribute to the growing body of evidence supporting the potential benefits of cognitive-behavioral approaches for maternal mental health. Further research with larger and more diverse samples is needed to confirm these effects and inform clinical practice.

Ethical Consideration

This article is derived from a Master’s thesis in Midwifery Counseling with ethics code (IR. ZUMS.REC.1396.334) and is registered in the Clinical Trials Registry with code IRCT20160521027994N4. Additionally, all methods were carried out according to relevant guidelines and regulations, and participants provided consent to participate in the study.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to sincerely thank the Deputy of Research and Technology at Zanjan University of Medical Sciences for their financial support of this study. The authors also extend their heartfelt appreciation to all mothers who participated in this study.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

Funding

The present article has been derived from the master’s thesis of the first author in Midwifery

Counseling (code: A-11-108-5), financially supported by the Research and Technology Vice-Chancellor of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' Contributions

Azadi Z: The study conception and design; data collection, interpretation, and manuscript preparation. Kharaghani R: The study design, the manuscript preparation, reading, revision, and approval, Ebrahimi L: The study design, the manuscript preparation, reading, revision, and approval, Emamgholi Khooshehchin T: The study was conceived and designed, analyzed, and interpreted, with manuscript preparation, reading, revision, and approval. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agreed to be personally accountable for their contributions.

Artificial Intelligence Utilization

During manuscript preparation, minor assistance from artificial intelligence (AI) tools was utilized to enhance English phrasing and improve the clarity of scientific writing. All analytical decisions and final editing were performed by the authors. The use of AI complied with ethical standards of academic publishing and did not replace the author's responsibility.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the corresponding author.

Full-Text: (89 Views)

Introduction

Abortion is defined as the termination of an intrauterine pregnancy up to the 20th week of gestation. Early pregnancy loss, which occurs during the first trimester (up to approximately the 13th week), is the most common type [1]. This experience is widely recognized as both a physically and emotionally distressing event [2]. Individuals with a history of early pregnancy loss exhibit a higher prevalence of mental disorders compared to those with normal pregnancies [3], constituting a significant risk to maternal mental health [4]. It can precipitate a range of psychological disorders, including depression, anxiety, and diminished satisfaction across various life domains [2,5]. Although the medical management of abortion often receives considerable attention, its psychological sequelae are frequently overlooked [6].

Stress represents a primary psychological consequence of abortion [7]. It can be defined as an individual's reaction to internal, external, or self-imposed pressure, resulting in physiological, psychological, and behavioral changes [8]. While not inherently negative and sometimes yielding potentially positive outcomes [9], persistent stress during pregnancy is particularly concerning. It triggers the release of hormones that, upon crossing the placental barrier, can induce irreversible effects on fetal psychological development [10]. Research further indicates that maternal anxiety or depressive symptomatology may be associated with an elevated risk of miscarriage [11]. Consequently, miscarriage is an established risk factor for the development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in affected women [12].

The loss of a pregnancy is thus one of the most profound emotional stressors a woman can endure, typically accompanied by a significant grief reaction [13]. Miscarriage or perinatal loss frequently initiates a substantial bereavement process. This mourning period serves as a vital adaptive mechanism for coping with the loss; however, inadequate psychological processing during this time can lead to complicated grief and associated psychopathologies, including anxiety, depression, and PTSD [13]. Grief plays a pivotal role in the development of these conditions, with psychological disorders often emerging as part of, or alongside, the natural grieving process [12]. In most affected women, depressive symptoms are most pronounced in the initial months following the loss and tend to attenuate over time [14].

The experience of abortion can also substantially diminish the quality of life. The World Health Organization defines quality of life as an individual's perception of their position in life within the context of their culture and value systems, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns [15]. It is a multidimensional, complex construct reflecting a personal evaluation of various life aspects, encompassing emotional responses, attitudes, fulfillment, life satisfaction, and contentment with work and relationships [16]. A key characteristic, widely acknowledged in social science, is its multidimensional and dynamic nature [17]. Pregnancy itself alters quality of life, often in ways perceived as unsatisfactory by pregnant women [18].

Women frequently experience diverse psychological complications after miscarriage that significantly impair their quality of life [19], with the poorest reported outcomes typically in the psychological domain [20]. Various interventions have been implemented to mitigate stress and enhance the quality of life in this population. These include psychological interventions, pharmacological approaches, and counseling, all of which have demonstrated efficacy in stress alleviation [21]. Although supportive counseling may not be universally recommended for all women post-abortion, it can be particularly beneficial for those experiencing high levels of psychological distress [22]. Correspondingly, Abu Shreida et al. demonstrated that psychological interventions reduce post-traumatic stress symptoms in women with a history of abortion [23]. Additionally, self-compassion training [24] and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) have shown positive impacts on quality of life in pregnant women with a history of pregnancy loss [25].

Cognitive-behavioral counseling represents an innovative and widely accepted approach in psychological treatment. Its core premise is that directly altering emotions is challenging; therefore, it focuses on modifying maladaptive thoughts and behaviors to effectively target distressing emotions. CBT equips individuals with skills to enhance awareness of their thoughts and feelings, and to understand the interplay between situations, cognitions, behaviors, and emotions [26].

A review of the existing literature reveals that most studies investigating post-abortion psychological challenges have focused on women with recurrent pregnancy loss, while the struggles of those experiencing a single abortion remain comparatively neglected. Furthermore, the majority of supportive interventions have been educational, and among the limited studies implementing counseling, a standardized, protocol-driven approach is often lacking.

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of individual cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) counseling on stress and quality of life in pregnant women with a history of spontaneous miscarriage, given the high psychological impact and limited support

Methods

Study Design

This study was a parallel, randomized controlled trial with a 1:1 allocation ratio. It was conducted after obtaining approval from the Deputy of Research at the University of Medical Sciences and registration on the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) with the code IRCT20160521027994N4. This trial was conducted in urban and rural health centers in Khodabandeh County and Zanjan City between 2018 and 2019.

Participants

Inclusion criteria comprised willingness to participate, a score of 19–37 on the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), pregnant women between 6 and 10 weeks of intrauterine pregnancy confirmed by ultrasound, absence of physical or mental illnesses, education level of at least middle school, and no exposure to major stressful events (e.g., death of a loved one, accidents, severe family conflicts, divorce, migration, or financial bankruptcy) in the six months before the study. Exclusion criteria included withdrawal from the study, pregnancy-related complications such as bleeding and abdominal pain as signs of miscarriage, or experiencing major stressful events during the research.

First, written consent was obtained from pregnant mothers to participate in the study.

Randomization

Sampling was initially conducted using a convenience method. Out of 821 pregnant women with a history of one abortion and a PSS score of 19–37, 72 eligible participants were enrolled. They were randomly assigned to intervention (A) and control (B) groups using block randomization. Eighteen blocks of four participants each were created, with possible combinations of AABB, BBAA, ABAB, BABA, ABBA, or BAAB. Blocks were randomly selected using a random number table, resulting in 36 participants per group. Post-intervention, three participants from the intervention group and three from each group during follow-up were excluded. Final analysis included data from 30 intervention and 31 control participants (Figure 1).To prevent bias, the intervention and control groups were identified only by numbers at the time of data entry, and the data analyst was unaware of the nature of the groups.

Blinding

Although participants were not blinded, group assignments were coded during data entry, and the analyst remained blinded to these codes throughout the data analysis.

Sample Size

Based on the methodology outlined by Jabari et al. [27], the sample size was calculated using a standard deviation of 1.7 for the intervention group and 2.3 for the control group for post-intervention outcomes, a mean difference of 1.5 units, a 95% confidence level (α = 0.05), and 80% statistical power. This calculation indicated a requirement of 29 participants per group. To account for a potential attrition rate of 20%, the sample size was increased, resulting in 36 participants per group. The total sample was therefore set at 72 pregnant women at 6–10 weeks of gestation. This determination was further corroborated by applying Cochran's formula with identical parameters (α = 0.05, power = 0.8, 95% CI), which yielded a minimum sample size of 60. After incorporating an additional 12 participants (six per group) to offset potential attrition, the final sample size remained 72 individuals.

Interventions:

Cognitive-behavioral counseling sessions were conducted following Antony et al.'s (2007) protocol [28]. The program consisted of 10 sessions designed to identify, challenge, and modify negative cognitions in individuals experiencing emotional difficulties such as depression, anxiety, stress, or excessive anger. The sessions included:

Due to the nature of the intervention, participants and the therapist were aware of group allocation. However, blinding of outcome assessors and the data analyst was not implemented, which is acknowledged as a limitation of the study.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were stress and quality of life. Data collection tools included:

Statistical Methods:

Data from the remaining participants were entered into SPSS-16, cleaned, and checked for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test, confirming a non-normal distribution (p < 0.05). Non-parametric tests were applied, including Mann-Whitney U for group comparisons, Friedman for repeated measures ranking, and chi-square for categorical variables.

Six participants were lost to follow-up (three from the intervention group and three from the control group), resulting in slightly unequal final sample sizes (30 vs. 31). An intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was not performed, which is acknowledged as a study limitation. Due to the small sample size, additional analyses to assess time and group effects or to report effect sizes were not feasible, and this limitation is discussed in the manuscript.

Results

The mean (standard deviation) age of participants in the intervention group was 28.1 (5.8) years, while in the control group, it was 27.7 (5.9) years. The cause of the previous miscarriage in all mothers was spontaneous abortion. A history of infertility was reported in 6.7% of both groups. Most mothers in the intervention group (43.3%) had a high school diploma, and similarly, the highest percentage in the control group (40%) also held a high school diploma. Based on the results of statistical tests, there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of demographic and obstetric characteristics before the intervention (Table 1).

Before the intervention, the highest mean quality of life in the intervention group was related to the social domain, with a score of 63.5 (14.8), while in the control group, it was also the social domain, with a score of 63.5 (12.8). Stress levels in the intervention group were 28.3 (4.2), compared to 28.0 (3.5) in the control group. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in any of the quality-of-life subscales or stress levels.

Immediately after the intervention, the highest mean quality of life in the intervention group was related to overall quality of life and general health, with a score of 70.8 (9.4), whereas in the control group, it was the psychological domain, with a score of 59.4 (16.9). Stress levels in the intervention group decreased to 19.9 (3.9), while in the control group, they remained at 28.0 (3.5). A statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups in the psychological domain (p = 0.016), social domain (p = 0.034), overall quality of life and general health (p < 0.001), and stress levels (p < 0.001). However, no significant differences were found in the physical or environmental domains. Two months after the intervention, the highest mean quality of life in the intervention group remained in the overall quality of life and general health domain, with a score of 71.2 (6.6), while in the control group, it was the social domain, with a score of 63.2 (11.7).

Table1. Comparison of Demographic and Obstetric Characteristics between the Intervention and Control Groups

Table 2. Comparison of Quality-of-Life Domain Scores and Stress Levels between the Intervention and Control Groups

Abortion is defined as the termination of an intrauterine pregnancy up to the 20th week of gestation. Early pregnancy loss, which occurs during the first trimester (up to approximately the 13th week), is the most common type [1]. This experience is widely recognized as both a physically and emotionally distressing event [2]. Individuals with a history of early pregnancy loss exhibit a higher prevalence of mental disorders compared to those with normal pregnancies [3], constituting a significant risk to maternal mental health [4]. It can precipitate a range of psychological disorders, including depression, anxiety, and diminished satisfaction across various life domains [2,5]. Although the medical management of abortion often receives considerable attention, its psychological sequelae are frequently overlooked [6].

Stress represents a primary psychological consequence of abortion [7]. It can be defined as an individual's reaction to internal, external, or self-imposed pressure, resulting in physiological, psychological, and behavioral changes [8]. While not inherently negative and sometimes yielding potentially positive outcomes [9], persistent stress during pregnancy is particularly concerning. It triggers the release of hormones that, upon crossing the placental barrier, can induce irreversible effects on fetal psychological development [10]. Research further indicates that maternal anxiety or depressive symptomatology may be associated with an elevated risk of miscarriage [11]. Consequently, miscarriage is an established risk factor for the development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in affected women [12].

The loss of a pregnancy is thus one of the most profound emotional stressors a woman can endure, typically accompanied by a significant grief reaction [13]. Miscarriage or perinatal loss frequently initiates a substantial bereavement process. This mourning period serves as a vital adaptive mechanism for coping with the loss; however, inadequate psychological processing during this time can lead to complicated grief and associated psychopathologies, including anxiety, depression, and PTSD [13]. Grief plays a pivotal role in the development of these conditions, with psychological disorders often emerging as part of, or alongside, the natural grieving process [12]. In most affected women, depressive symptoms are most pronounced in the initial months following the loss and tend to attenuate over time [14].

The experience of abortion can also substantially diminish the quality of life. The World Health Organization defines quality of life as an individual's perception of their position in life within the context of their culture and value systems, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns [15]. It is a multidimensional, complex construct reflecting a personal evaluation of various life aspects, encompassing emotional responses, attitudes, fulfillment, life satisfaction, and contentment with work and relationships [16]. A key characteristic, widely acknowledged in social science, is its multidimensional and dynamic nature [17]. Pregnancy itself alters quality of life, often in ways perceived as unsatisfactory by pregnant women [18].

Women frequently experience diverse psychological complications after miscarriage that significantly impair their quality of life [19], with the poorest reported outcomes typically in the psychological domain [20]. Various interventions have been implemented to mitigate stress and enhance the quality of life in this population. These include psychological interventions, pharmacological approaches, and counseling, all of which have demonstrated efficacy in stress alleviation [21]. Although supportive counseling may not be universally recommended for all women post-abortion, it can be particularly beneficial for those experiencing high levels of psychological distress [22]. Correspondingly, Abu Shreida et al. demonstrated that psychological interventions reduce post-traumatic stress symptoms in women with a history of abortion [23]. Additionally, self-compassion training [24] and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) have shown positive impacts on quality of life in pregnant women with a history of pregnancy loss [25].

Cognitive-behavioral counseling represents an innovative and widely accepted approach in psychological treatment. Its core premise is that directly altering emotions is challenging; therefore, it focuses on modifying maladaptive thoughts and behaviors to effectively target distressing emotions. CBT equips individuals with skills to enhance awareness of their thoughts and feelings, and to understand the interplay between situations, cognitions, behaviors, and emotions [26].

A review of the existing literature reveals that most studies investigating post-abortion psychological challenges have focused on women with recurrent pregnancy loss, while the struggles of those experiencing a single abortion remain comparatively neglected. Furthermore, the majority of supportive interventions have been educational, and among the limited studies implementing counseling, a standardized, protocol-driven approach is often lacking.

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of individual cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) counseling on stress and quality of life in pregnant women with a history of spontaneous miscarriage, given the high psychological impact and limited support

Methods

Study Design

This study was a parallel, randomized controlled trial with a 1:1 allocation ratio. It was conducted after obtaining approval from the Deputy of Research at the University of Medical Sciences and registration on the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) with the code IRCT20160521027994N4. This trial was conducted in urban and rural health centers in Khodabandeh County and Zanjan City between 2018 and 2019.

Participants

Inclusion criteria comprised willingness to participate, a score of 19–37 on the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), pregnant women between 6 and 10 weeks of intrauterine pregnancy confirmed by ultrasound, absence of physical or mental illnesses, education level of at least middle school, and no exposure to major stressful events (e.g., death of a loved one, accidents, severe family conflicts, divorce, migration, or financial bankruptcy) in the six months before the study. Exclusion criteria included withdrawal from the study, pregnancy-related complications such as bleeding and abdominal pain as signs of miscarriage, or experiencing major stressful events during the research.

First, written consent was obtained from pregnant mothers to participate in the study.

Randomization

Sampling was initially conducted using a convenience method. Out of 821 pregnant women with a history of one abortion and a PSS score of 19–37, 72 eligible participants were enrolled. They were randomly assigned to intervention (A) and control (B) groups using block randomization. Eighteen blocks of four participants each were created, with possible combinations of AABB, BBAA, ABAB, BABA, ABBA, or BAAB. Blocks were randomly selected using a random number table, resulting in 36 participants per group. Post-intervention, three participants from the intervention group and three from each group during follow-up were excluded. Final analysis included data from 30 intervention and 31 control participants (Figure 1).To prevent bias, the intervention and control groups were identified only by numbers at the time of data entry, and the data analyst was unaware of the nature of the groups.

Blinding

Although participants were not blinded, group assignments were coded during data entry, and the analyst remained blinded to these codes throughout the data analysis.

Sample Size

Based on the methodology outlined by Jabari et al. [27], the sample size was calculated using a standard deviation of 1.7 for the intervention group and 2.3 for the control group for post-intervention outcomes, a mean difference of 1.5 units, a 95% confidence level (α = 0.05), and 80% statistical power. This calculation indicated a requirement of 29 participants per group. To account for a potential attrition rate of 20%, the sample size was increased, resulting in 36 participants per group. The total sample was therefore set at 72 pregnant women at 6–10 weeks of gestation. This determination was further corroborated by applying Cochran's formula with identical parameters (α = 0.05, power = 0.8, 95% CI), which yielded a minimum sample size of 60. After incorporating an additional 12 participants (six per group) to offset potential attrition, the final sample size remained 72 individuals.

Interventions:

Cognitive-behavioral counseling sessions were conducted following Antony et al.'s (2007) protocol [28]. The program consisted of 10 sessions designed to identify, challenge, and modify negative cognitions in individuals experiencing emotional difficulties such as depression, anxiety, stress, or excessive anger. The sessions included:

- Introduction to stress and pregnancy-related reactions.

- Pregnancy stressors and their consequences.

- Physiological stress responses and management techniques.

- Psychological stress responses and cognitive restructuring strategies.

- Autogenic training for relaxation and rational thinking.

- Autogenic training focusing on heart rate, breathing, and coping strategies.

- Guided imagery and development of effective coping responses.

- Mantra meditation and anger management techniques.

- Breathing exercises and assertiveness training.

- Integration of imagery, meditation, social support, and session summaries.

Due to the nature of the intervention, participants and the therapist were aware of group allocation. However, blinding of outcome assessors and the data analyst was not implemented, which is acknowledged as a limitation of the study.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were stress and quality of life. Data collection tools included:

- Demographic and obstetric checklist (age, time since abortion, infertility history, education, spouse’s education/occupation, economic status).

- Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) [29], scoring 0–56 (0–18: low stress; 19–37: moderate; 38–56: high). Cronbach’s alpha: 0.73.

- WHO Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL) [30], with 24 items across physical (7–35), psychological (6–30), social (3–15), environmental (8–40), and general health (2–10) domains. Raw scores were converted to a 0–100 scale. Persian version reliability: Cronbach’s alpha 0.7.

- General Health Questionnaire: General Health Questionnaire: The 28-question version of this questionnaire has the highest validity, sensitivity, and specificity. This questionnaire assesses symptoms of mental disorder within the past month up to the time of the test. The General Health Questionnaire is a screening questionnaire based on a self-report method that is used to identify people with a mental disorder. The individual's score on each of the subscales will range from 0 to 21, and the entire questionnaire will range from 0 to 84. In this study, this questionnaire was used to exclude people with mental disorders [31].

Statistical Methods:

Data from the remaining participants were entered into SPSS-16, cleaned, and checked for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test, confirming a non-normal distribution (p < 0.05). Non-parametric tests were applied, including Mann-Whitney U for group comparisons, Friedman for repeated measures ranking, and chi-square for categorical variables.

Six participants were lost to follow-up (three from the intervention group and three from the control group), resulting in slightly unequal final sample sizes (30 vs. 31). An intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was not performed, which is acknowledged as a study limitation. Due to the small sample size, additional analyses to assess time and group effects or to report effect sizes were not feasible, and this limitation is discussed in the manuscript.

Results

The mean (standard deviation) age of participants in the intervention group was 28.1 (5.8) years, while in the control group, it was 27.7 (5.9) years. The cause of the previous miscarriage in all mothers was spontaneous abortion. A history of infertility was reported in 6.7% of both groups. Most mothers in the intervention group (43.3%) had a high school diploma, and similarly, the highest percentage in the control group (40%) also held a high school diploma. Based on the results of statistical tests, there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of demographic and obstetric characteristics before the intervention (Table 1).

Before the intervention, the highest mean quality of life in the intervention group was related to the social domain, with a score of 63.5 (14.8), while in the control group, it was also the social domain, with a score of 63.5 (12.8). Stress levels in the intervention group were 28.3 (4.2), compared to 28.0 (3.5) in the control group. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in any of the quality-of-life subscales or stress levels.

Immediately after the intervention, the highest mean quality of life in the intervention group was related to overall quality of life and general health, with a score of 70.8 (9.4), whereas in the control group, it was the psychological domain, with a score of 59.4 (16.9). Stress levels in the intervention group decreased to 19.9 (3.9), while in the control group, they remained at 28.0 (3.5). A statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups in the psychological domain (p = 0.016), social domain (p = 0.034), overall quality of life and general health (p < 0.001), and stress levels (p < 0.001). However, no significant differences were found in the physical or environmental domains. Two months after the intervention, the highest mean quality of life in the intervention group remained in the overall quality of life and general health domain, with a score of 71.2 (6.6), while in the control group, it was the social domain, with a score of 63.2 (11.7).

Table1. Comparison of Demographic and Obstetric Characteristics between the Intervention and Control Groups

| Variable | Intervention Group | Control Group | p |

| Age, M (SD) | 28.1 (5.8) | 27.7 (5.9) | 0.847 |

| Infertility | |||

| Yes | 2 (6.7%) | 2 (6.7%) | 1 |

| No | 28 (93.3%) |

28 (93.3%) |

|

| Education | |||

| Secondary School | 9 (30.0%) | 11 (36.7%) | 1 |

| Diploma | 13 (43.3%) |

12 (40.0%) |

|

| Bachelor’s Degree | 6 (20.0%) | 5 (16.7%) | |

| Master’s Degree | 2 (6.7%) | 2 (6.7%) | |

| Spouse’s Education | |||

| Secondary School | 8 (26.7%) | 5 (16.7%) | 0.36 |

| Diploma | 16 (53.3%) |

17 (56.7%) |

|

| Bachelor’s Degree | 4 (13.3%) | 6 (20.0%) | |

| Master’s Degree | 2 (6.7%) | 2 (6.7%) | |

| Occupation | |||

| Unemployed | 19 (63.3%) |

19 (63.3%) |

0.918 |

| Part-time | 3 (10.0%) | 5 (16.7%) | |

| Full-time | 7 (23.3%) | 4 (13.3%) | |

| Student | 1 (3.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | |

| Spouse’s Occupation | |||

| Part-time | 6 (20.0%) | 5 (16.7%) | 0.741 |

| Full-time | 24 (80.0%) |

25(83.3%) |

|

| Economic Status | |||

| Poor | 1 (3.3%) | 1 (3.3%) | 0.982 |

| Moderate | 22 (73.3%) | 23 (76.7%) | |

| Good | 7 (23.3%) | 6 (20.0%) |

| Time Point | Domain | Intervention Group, M (SD) | Control Group, M (SD) | p |

| Before Intervention | ||||

| Physical Health | 43.6 (22.2) | 46.4 (24.6) | 0.474 | |

| Psychological | 56.0 (20.8) | 60.0 (19.1) | 0.464 | |

| Social Relationships | 63.5 (14.8) | 63.8 (12.8) | 0.916 | |

| Environment | 54.0 (12.7) | 53.5 (13.1) | 0.982 | |

| Overall QoL & General Health | 60.4 (22.9) | 60.8 (26.0) | 0.827 | |

| Stress | 28.3 (4.2) | 28.2 (3.4) | 0.929 | |

| After Intervention | ||||

| Physical Health | 46.3 (21.1) | 46.8 (23.9) | 0.770 | |

| Psychological | 67.8 (15.2) | 59.4 (16.9) | 0.016 | |

| Social Relationships | 71.3 (9.3) | 64.2 (12.2) | 0.034 | |

| Environment | 57.3 (10.8) | 53.1 (12.2) | 0.261 | |

| Overall QoL & General Health | 70.8 (9.4) | 55.4 (16.9) | <0.001 | |

| Stress | 19.9 (3.9) | 28.0 (3.5) | <0.001 | |

| Two Months After Intervention | ||||

| Physical Health | 49.8 (19.8) | 46.4 (24.2) | 0.707 | |

| Psychological | 69.3 (15.2) | 59.4 (18.1) | 0.013 | |

| Social Relationships | 69.1 (11.6) | 63.2 (11.7) | 0.022 | |

| Environment | 59.2 (11.7) | 51.9 (11.7) | 0.026 | |

| Overall QoL & General Health | 71.2 (6.6) | 52.0 (13.9) | <0.001 | |

| Stress | 19.7 (3.5) | 27.9 (3.5) | <0.001 |

Table 3. Results of the Friedman Test for Intra-Group Changes across Measurement Time Points

| Variable | Group | Mean Rank (Before) | Mean Rank (After) | Mean Rank (2-Month Follow-up) | χ² | df | p | Kendall's W |

| Stress | Intervention | 2.98 | 1.48 | 1.53 | 46.248 | 2 | < 0.001 | 0.771 |

| Control | 2.18 | 1.97 | 1.85 | 2.040 | 2 | 0.361 | 0.034 | |

| Overall Quality of Life | Intervention | 1.72 | 2.13 | 2.15 | 5.106 | 2 | 0.078 | 0.085 |

| Control | 2.22 | 1.98 | 1.80 | 3.376 | 2 | 0.185 | 0.056 | |

| Physical Domain | Intervention | 1.63 | 2.03 | 2.33 | 13.455 | 2 | 0.001 | 0.224 |

| Control | 1.93 | 2.08 | 1.98 | 1.000 | 2 | 0.607 | 0.017 | |

| Psychological Domain | Intervention | 1.27 | 2.33 | 2.40 | 36.400 | 2 | < 0.001 | 0.607 |

| Control | 2.12 | 1.93 | 1.95 | 1.104 | 2 | 0.576 | 0.018 | |

| Social Domain | Intervention | 1.55 | 2.32 | 2.13 | 19.233 | 2 | < 0.001 | 0.321 |

| Control | 2.02 | 2.10 | 1.88 | 1.755 | 2 | 0.416 | 0.029 | |

| Environmental Domain | Intervention | 1.63 | 2.12 | 2.25 | 9.475 | 2 | 0.009 | 0.158 |

| Control | 2.07 | 2.03 | 1.90 | 0.982 | 2 | 0.612 | 0.016 |

Stress levels in the intervention group were 19.7 (3.5), compared to 27.9 (3.5) in the control group. Significant differences were observed between the two groups in the psychological domain (p = 0.013), social domain (p= 0.022), environmental domain (p= 0.026), overall quality of life and general health (p< 0.001), and stress levels (p < 0.001). However, no significant difference was found in the physical domain.

The results of the Friedman test indicate that the intervention group experienced statistically significant improvements over time in most variables, with large effect sizes observed for stress (Kendall's W = 0.771) and the psychological domain (Kendall's W = 0.607), reflecting substantial reductions in stress and enhancements in psychological well-being. Medium effects were noted for the social domain (Kendall's W = 0.321), while small to medium effects were found for the physical domain (Kendall's W = 0.224) and environmental domain (Kendall's W = 0.158). In contrast, no significant changes occurred in the control group, with all effect sizes negligible (Kendall's W < 0.05), demonstrating that the intervention had a meaningful and sustained impact on the intervention group without similar effects in the control group (Table 3).

Following the significant results of the Friedman test (Table 3), post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to identify the specific time points where significant changes occurred within each group (Table 4).

The results of the Friedman test indicate that the intervention group experienced statistically significant improvements over time in most variables, with large effect sizes observed for stress (Kendall's W = 0.771) and the psychological domain (Kendall's W = 0.607), reflecting substantial reductions in stress and enhancements in psychological well-being. Medium effects were noted for the social domain (Kendall's W = 0.321), while small to medium effects were found for the physical domain (Kendall's W = 0.224) and environmental domain (Kendall's W = 0.158). In contrast, no significant changes occurred in the control group, with all effect sizes negligible (Kendall's W < 0.05), demonstrating that the intervention had a meaningful and sustained impact on the intervention group without similar effects in the control group (Table 3).

Following the significant results of the Friedman test (Table 3), post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to identify the specific time points where significant changes occurred within each group (Table 4).

Table 4. Post-hoc Comparisons of Stress and Quality of Life Scores across Time Points Using the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test

| Measure | Comparison | Group | Z | p (two-tailed) |

| Stress | Before vs. Immediately After | Intervention | -4.711 | < 0.001 |

| Control | -0.550 | 0.582 | ||

| Before vs. 2 Months After | Intervention | -4.787 | < 0.001 | |

| Control | -0.505 | 0.614 | ||

| Immediately After vs. 2 Months After | Intervention | -0.509 | 0.611 | |

| Control | -0.160 | 0.873 | ||

| Overall QoL | Before vs. Immediately After | Intervention | -2.679 | 0.007 |

| Control | -1.803 | 0.071 | ||

| Before vs. 2 Months After | Intervention | -2.652 | 0.008 | |

| Control | -1.910 | 0.056 | ||

| Immediately After vs. 2 Months After | Intervention | -0.258 | 0.796 | |

| Control | -1.537 | 0.124 | ||

| Physical QoL | Before vs. Immediately After | Intervention | -1.836 | 0.066 |

| Control | -0.789 | 0.430 | ||

| Before vs. 2 Months After | Intervention | -2.847 | 0.004 | |

| Control | -0.368 | 0.713 | ||

| Immediately After vs. 2 Months After | Intervention | -1.933 | 0.053 | |

| Control | -1.000 | 0.317 | ||

| Psychological QoL | Before vs. Immediately After | Intervention | -4.248 | < 0.001 |

| Control | -0.264 | 0.791 | ||

| Before vs. 2 Months After | Intervention | -4.180 | < 0.001 | |

| Control | -0.183 | 0.855 | ||

| Immediately After vs. 2 Months After | Intervention | -1.109 | 0.268 | |

| Control | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Social QoL | Before vs. Immediately After | Intervention | -3.558 | < 0.001 |

| Control | -0.575 | 0.565 | ||

| Before vs. 2 Months After | Intervention | -2.678 | 0.007 | |

| Control | -0.408 | 0.683 | ||

| Immediately After vs. 2 Months After | Intervention | -1.634 | 0.102 | |

| Control | -0.780 | 0.436 | ||

| Environmental QoL | Before vs. Immediately After | Intervention | -2.368 | 0.018 |

| Control | -0.240 | 0.810 | ||

| Before vs. 2 Months After | Intervention | -3.029 | 0.002 | |

| Control | -0.168 | 0.867 | ||

| Immediately After vs. 2 Months After | Intervention | -1.622 | 0.105 | |

| Control | -0.458 | 0.647 |

In the intervention group, significant improvements were observed from baseline to post-intervention and from baseline to the two-month follow-up for stress (both p < 0.001), the psychological domain (both p < 0.001), the social domain (p < 0.001 and p = 0.007, respectively), the environmental domain (p = 0.018 and p = 0.002, respectively), and overall quality of life (p = 0.007 and p = 0.008, respectively).

For the physical domain, a significant improvement was found only at the two-month follow-up compared to baseline (p = 0.004). No significant differences were observed between the post-intervention and two-month follow-up scores for any variable in the intervention group (all p > 0.05), indicating the improvements were sustained.

In contrast, within the control group, none of the pairwise comparisons between the three time points reached statistical significance for any of the measured variables (all p > 0.05) (Table 4).

Discussion

The findings of this clinical trial demonstrate that individually administered cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) significantly reduced stress and improved quality of life among pregnant women with a history of spontaneous abortion. Significant differences between the intervention and control groups were observed post-intervention immediately and were sustained at the two-month follow-up across stress levels and most quality-of-life domains. The intervention yielded a very large effect on stress reduction (Kendall’s W = 0.771) and a large effect on improving psychological well-being (Kendall’s W = 0.607), with medium effects observed for the social domain and small-to-medium effects for the environmental domain. This provides robust evidence for the durable efficacy of a structured, face-to-face CBT protocol in enhancing psychological health during a subsequent pregnancy.

The observed reduction in stress aligns with findings from other studies that employed various counseling approaches for pregnant women with a history of pregnancy loss [12, 22, 23]. While the literature confirms that psychological interventions can alleviate stress, many prior studies have focused on women with recurrent miscarriage, and interventions have often been educational or lacked a standardized theoretical foundation [12,22]. This study addresses notable gaps by targeting women with a single prior miscarriage, an often-overlooked population, and implementing a manualized CBT protocol. The inclusion of a two-month follow-up further demonstrates the sustainability of the benefits, suggesting the acquisition of lasting coping skills.

The positive impact of CBT on multiple quality of life domains is consistent with prior research. Heratzadeh et al. reported similar benefits on quality of life from self-compassion training [24], while Silva et al. found CBT improved quality of life and social functioning post-miscarriage [18]. Furthermore, Hiltunen et al. indicated that CBT could enhance quality of life even when delivered by less experienced therapists [32]. The mechanism through which CBT confers benefit can be explained by its focus on modifying cognitive and behavioral responses to stress. Through cognitive restructuring, individuals develop rational self-talk, which reduces psychological distress in anxiety-provoking situations [33]. Techniques such as behavioral activation help counteract depression and amotivation by increasing engagement in pleasurable activities, thereby revitalizing motivation and life satisfaction through the modification of core beliefs [34].

The lack of a significant effect in the physical domain of quality of life may be attributable to the predominant hormonal and physiological changes of pregnancy, which are less amenable to psychosocial intervention. However, as the primary challenges for this population are psychological, CBT remains a highly suitable supportive approach. This study has several limitations that should be considered. First, the reliance on self-report measures may introduce response bias. Second, participant retention challenges occurred, and the small sample size, drawn from a specific geographic area, limits the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. The small sample size also restricted our ability to conduct more robust analyses of interaction effects and to report a comprehensive range of effect size measures. Third, the inability to blind participants to the intervention and the lack of blinding for outcome assessors may have introduced performance and measurement bias, particularly for self-reported outcomes like quality of life. Finally, the lack of an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, due to dropout, may have influenced the effect size estimates, potentially overstating the intervention's efficacy. Despite these limitations, a key strength is the use of individual, face-to-face CBT counseling, which facilitated open emotional expression, personalized feedback, and structured between-session assignments to promote skill acquisition and reflection.In conclusion, individual CBT counseling appears to be an effective and sustainable intervention for reducing stress and improving quality of life in pregnant women with a prior miscarriage. Future research with larger, more diverse samples and rigorous methodological designs, including blinded outcome assessment and ITT analysis, is recommended to confirm these findings and facilitate the integration of this approach into standard perinatal mental health pathways.

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that individual cognitive-behavioral counseling may help reduce stress and improve most domains of quality of life in pregnant women with a history of spontaneous abortion. These findings contribute to the growing body of evidence supporting the potential benefits of cognitive-behavioral approaches for maternal mental health. Further research with larger and more diverse samples is needed to confirm these effects and inform clinical practice.

Ethical Consideration

This article is derived from a Master’s thesis in Midwifery Counseling with ethics code (IR. ZUMS.REC.1396.334) and is registered in the Clinical Trials Registry with code IRCT20160521027994N4. Additionally, all methods were carried out according to relevant guidelines and regulations, and participants provided consent to participate in the study.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to sincerely thank the Deputy of Research and Technology at Zanjan University of Medical Sciences for their financial support of this study. The authors also extend their heartfelt appreciation to all mothers who participated in this study.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

Funding

The present article has been derived from the master’s thesis of the first author in Midwifery

Counseling (code: A-11-108-5), financially supported by the Research and Technology Vice-Chancellor of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' Contributions

Azadi Z: The study conception and design; data collection, interpretation, and manuscript preparation. Kharaghani R: The study design, the manuscript preparation, reading, revision, and approval, Ebrahimi L: The study design, the manuscript preparation, reading, revision, and approval, Emamgholi Khooshehchin T: The study was conceived and designed, analyzed, and interpreted, with manuscript preparation, reading, revision, and approval. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agreed to be personally accountable for their contributions.

Artificial Intelligence Utilization

During manuscript preparation, minor assistance from artificial intelligence (AI) tools was utilized to enhance English phrasing and improve the clarity of scientific writing. All analytical decisions and final editing were performed by the authors. The use of AI complied with ethical standards of academic publishing and did not replace the author's responsibility.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the corresponding author.

Type of Study: Orginal research |

Subject:

Midwifery

References

1. Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Spong CY, Dash JS, Hoffman BL, et al. Williams Obstetrics. 26th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2022.

2. Huss B. Well-being before and after pregnancy termination: the consequences of abortion and miscarriage on satisfaction with various domains of life. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2021;22(6):2803-28. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00350-5]

3. Hosseini Haji Z, Aradmehr M, Irani M, Namazi Nia M. Comparison of the relative risk of stress, anxiety, and depression in women after miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, and normal pregnancy: A cross-sectional study. Iranian Journal of Gynecology, Obstetrics And Infertility. 2023;26(5):49-60. [https://doi.org/10.22038/ijogi.2023.22960]

4. Herbert D, Young K, Pietrusińska M, MacBeth A. The mental health impact of perinatal loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2022;297:118-29. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.026] [PMID]

5. Masten M, Campbell O, Horvath S, Zahedi-Spung L. Abortion and Mental Health and Wellbeing: A Contemporary Review of the Literature. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2024;26(12):877-84. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-024-01557-6] [PMID]

6. Carthew J, Gannon K. Barriers to Accessing Psychological Support Following Early Miscarriage: Perspectives of the IAPT Perinatal Champion. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2024 Nov 21;23:1-17. [https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2024.2433155] [PMID]

7. Kukulskienė M, Žemaitienė N. Postnatal depression and post-traumatic stress risk following miscarriage. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(11):6515. [https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116515] [PMID]

8. Cranwell-Ward J, Abbey A. What is Stress? In: Organizational Stress. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2005. p. 27-38. [https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230522800]

9. Updegraff JA, Taylor SE. From vulnerability to growth: Positive and negative effects of stressful life events. In: Loss and trauma. Routledge; 2021. p. 3-28. [https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315783345-2]

10. Collins JM, Keane JM, Deady C, Khashan AS, McCarthy FP, O'Keeffe GW, et al. Prenatal stress impacts foetal neurodevelopment: Temporal windows of gestational vulnerability. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2024;164:105793. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2024.105793] [PMID]

11. Kulathilaka S, Hanwella R, De Silva V. Depressive Disorder and Grief Following Spontaneous Abortion. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:100. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0812-y] [PMID]

12. Campillo ISL, Meaney S, McNamara K, O'Donoghue K. Psychological and support interventions to reduce levels of stress, anxiety or depression on women's subsequent pregnancy with a history of miscarriage: an empty systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e017802. [https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017802] [PMID]

13. Díaz-Pérez E, Haro G, Echeverria I. Psychopathology Present in Women after Miscarriage or Perinatal Loss: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry International. 2023;4(2):126-35. [https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint4020015]

14. Mergl R, Quaatz SM, Lemke V, Allgaier AK. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms in women with previous miscarriages or stillbirths - A systematic review. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2024;169:84-96. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.11.021] [PMID]

15. Melo-Oliveira ME, Sá-Caputo D, Bachur JA, Paineiras-Domingos LL, Sonza A, Lacerda AC, et al. Reported quality of life in countries with cases of COVID19: a systematic review. Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine. 2021;15(2):213-20. [https://doi.org/10.1080/17476348.2021.1826315] [PMID]

16. Theofilou P. Quality of life: definition and measurement. Europe's Journal of Psychology. 2013;9(1):150-62. [https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v9i1.337]

17. Santacreu M, Bustillos A, Fernandez-Ballesteros R. Multidimensional/multisystems/multinature indicators of quality of life: Cross-cultural evidence from Mexico and Spain. Social Indicators Research. 2016;126(2):467-82. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0906-9]

18. Lagadec N, Steinecker M, Kapassi A, Magnier AM, Chastang J, Robert S, et al. Factors influencing the quality of life of pregnant women: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2018;18(1):455. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2087-4] [PMID]

19. Salarfard M, Ghannadkafi M, Vaghee S, Behnam Vashani H, Mirzakhani K. Investigating the effect of emotional disclosure on the quality of life of women after abortion: a randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Psychology. 2025;13(1):1051. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-03355-y] [PMID]

20. Iwanowicz-Palus G, Mróz M, Bień A. Quality of life, social support and self-efficacy in women after a miscarriage. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):16. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01662-z] [PMID]

21. Nikčević AV, Kuczmierczyk AR, Nicolaides KH. The influence of medical and psychological interventions on women's distress after miscarriage. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2007;63(3):283-90. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.04.004] [PMID]

22. Kong G, Chung T, Lok I. The impact of supportive counselling on women's psychological wellbeing after miscarriage-a randomised controlled trial. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2014;121(10):1253-62. [https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12908] [PMID]

23. Shereda HMA, Rashed A, Shokr E. Effect of psychological intervention on post-traumatic stress symptoms and pregnancy outcomes among women with previous recurrent abortion. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice. 2018;8(12):123-34. [https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v8n12p123]

24. Heratzadeh FM. The Effectiveness of Self-Compassion Training on Anxiety and Quality of Life in Pregnant Women with Abortion in 1395-96 in Yazd. International Conference on Psychology Shandiz Higher Education Institute; 2017.

25. Silva ACdO, Nardi AE. Cognitive-behavioral therapy to miscarriage: results from the use of a grief therapy protocol. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry (São Paulo).2011;38:122-4. [https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-60832011000300007]

26. Cully JA, Teten AL. A Therapist's Guide to Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Houston: Department of Veterans Affairs South Central MIRECC; 2008. Chapter 1, p. 6.

27. Jabari Z, Hashemi H, Haghayegh A. Effect of cognitive-behavioral stress management on stress, anxiety and Depression in pregnant women. Journal of Health System Research. 2013;8(7):1341-8. [http://hsr.mui.ac.ir/article-1-479-fa.html]

28. Anthony M, Ironson G, Schneiderman N. A practical guide to managing stress through cognitive-behavioral methods. Translated by Jokar S, Al-Mohammad SJ, Taher Neshatdoost H. 1st ed. Isfahan: Isfahan University of Science and Technology; 2010.

29. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24(4):385-96. [https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404] [PMID]

30. World Health Organization. The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHO/QOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Social Science and Medicine. 1995;41(10):1403-9. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-k] [PMID]

31. Noorbala A, Mohammad K. The validation of general health questionnaire-28 as a psychiatric screening tool. Hakim Research Journal. 2009;11(4):47-53. [http://hakim.tums.ac.ir/article-1-464-en.html]

32. Hiltunen AJ, Kocys E, Perrin‐Wallqvist R. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy: An evaluation of therapies provided by trainees at a university psychotherapy training center. PsyCh Journal. 2013;2(2):101-12. [https://doi.org/10.1002/pchj.23] [PMID]

33. Shirazian S, Smaldone A, Rao MK, Silberzweig J, Jacobson AM, Fazzari M, et al. A protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial to assess the feasibility and effect of a cognitive behavioral intervention on quality of life for patients on hemodialysis. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2018;73:51-60. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2018.08.012] [PMID]

34. de Beurs E, Carlier I, van Hemert A. Psychopathology and health-related quality of life as patient-reported treatment outcomes: evaluation of concordance between the brief symptom inventory (BSI) and the short form-36 (SF-36) in psychiatric outpatients. Quality of Life Research. 2022;31(5):1461-71. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-03019-5] [PMID]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |